This is the third part of my notes on a re-watch of David Lean’s Dr Zhivago, a 1965 historical epic about the Russian Revolution. I’m going through it with an eye to historical accuracy.

Here is part one…

And here is part two.

The first two parts have been mixed – sometimes the crew really seem to have done their homework but we’ve also seen some things changed for the sake of simplicity (fair enough), some big things changed in order to reinforce the movie’s theme (Not so fair enough), and some things changed for no apparent reason at all.

Now it’s time to get to the part that most interests me, the film’s presentation of the Civil War. Unfortunately, it’s messier than anything we’ve seen so far.

The burned village

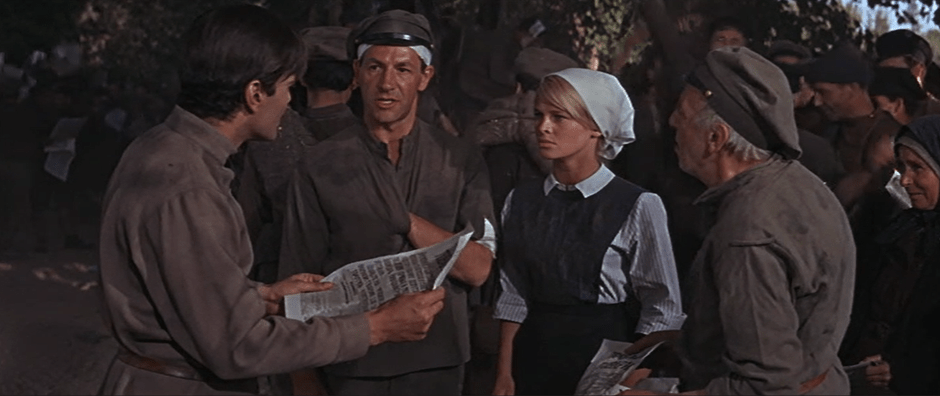

Yuri and his family are on a train passing through the Ural Mountains when they see a burned-out village and, on rescuing a woman from the ruins, learn that the Red commander Strelnikov ordered the burning to punish the villagers, who were falsely accused of selling horses to the White Armies. There are several ways that this is implausible.

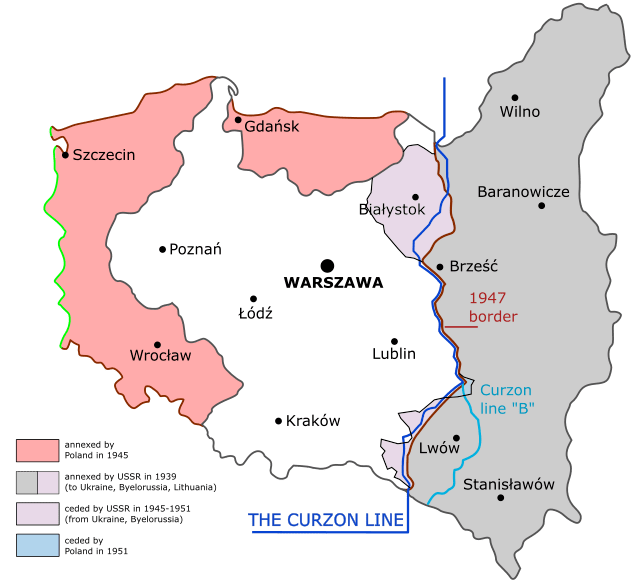

First, this is winter 1917-18 in the northern Urals. Until the Czechoslovak Revolt of May 1918 this was a peaceful region. There are no Whites here to buy horses. Maybe this could be happening at this time in the Don Country or Turkestan, ie thousands of kilometres away. But not here.

Even in the Don Country, or one of the other places where strings of battles flared up and died down at this time, we would be unlikely to see the burning of a village.

The Reds did worse things than this during the Civil War. But at this point in the movie we are only a few months out from October. The war has not begun yet, the cycles of violence have not had a few goes-around yet. And when we do see Red reprisals against a village, these would be targeted against the wealthier inhabitants.

What kind of atrocity would be plausible? A little later, food detachments descended on villages to confiscate surplus grain, and this naturally led to conflict. A scene serving the same purpose but involving some excess by a food detachment would make sense here, and the chronological fudge would be forgivable.

Strelnikov, armoured trains, Red Army

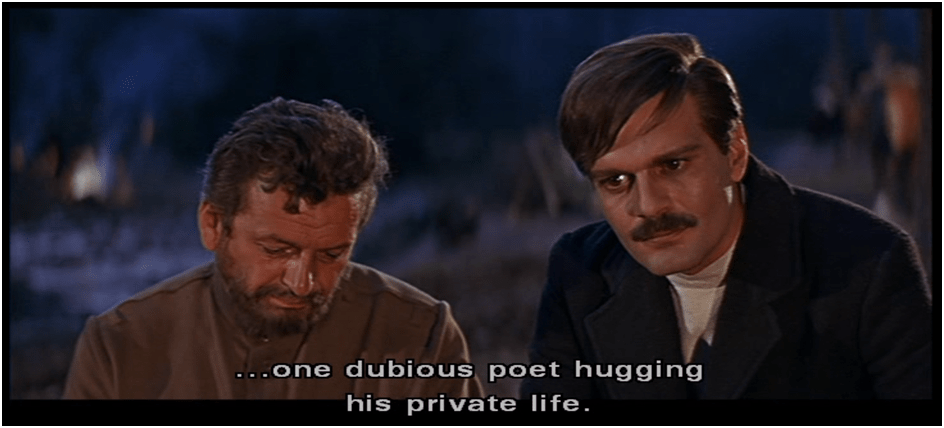

Yuri goes for a walk while the train is stopped, and stumbles on an armoured train commanded by Strelnikov (a nom de guerre that means something like ‘shooter’). His real name is Antipov and he is Lara’s estranged husband. This is another of those scenes that gives the impression that revolutionaries were grievously offended whenever a man wrote poetry.

One of my readers, a socialist like myself, sent me this message regarding Antipov/ Strelnikov:

‘Hey interesting take on Dr Zhivago. I always assumed that Antipov was based on a crude portrayal of Trotsky ie not in bolsheviks or mensheviks, total fanatic and bordering on a latter day incel (‘the personal life in Russia is dead’ because of revolution, actually Trotsky wrote on how the revolution awakened the Russian personality [after] years of oppression) and then there’s his role in civil war later in the film.’

I replied:

‘Yes, the armoured train etc. maybe the filmmakers were going for Trotsky […] I see him more as one of these very romantic left SR types [members of the Left Socialist Revolutionary party, the Bolsheviks’ early coalition partners] who zigzags between sentimentality and ultra leftism […] He seems to me a lot like an early Red Army commander named Muraviev although important differences too.’

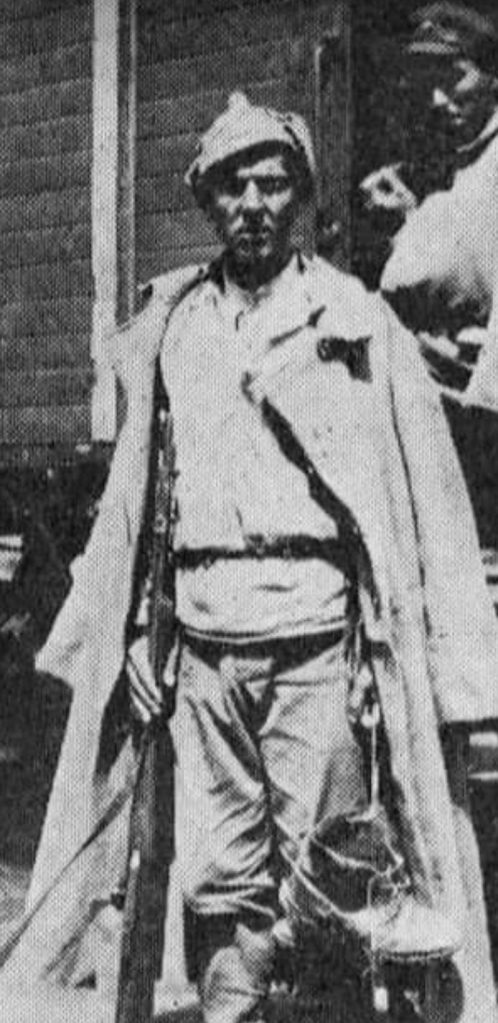

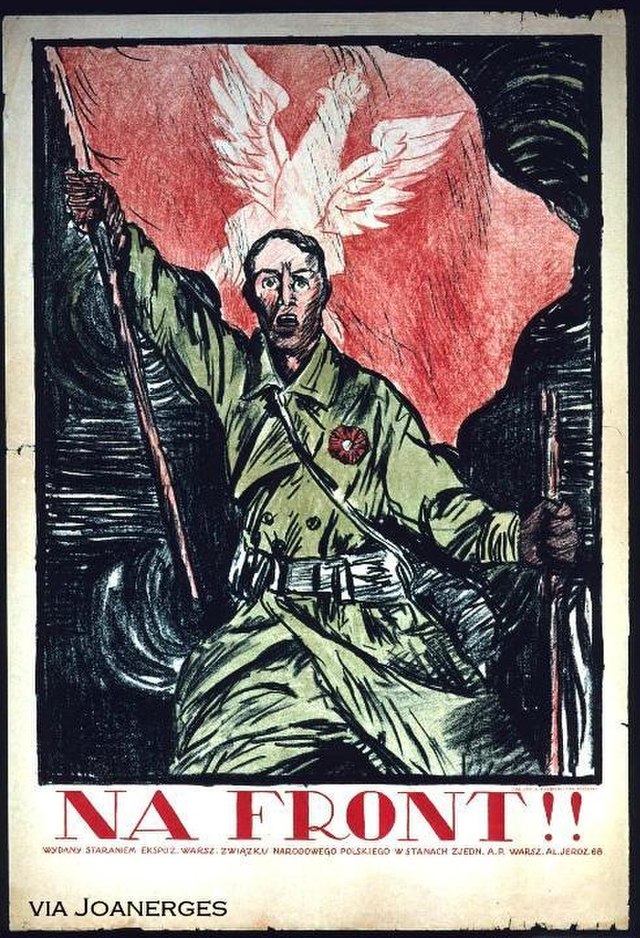

The first three de facto commanders of the Red Army (the above-mentioned Muraviev, then Vacietis and Kamenev) were non-Bolsheviks. Cooperation with the other parties and non-party individuals was the rule in these early days, especially with Left SRs and anarchists. That Antipov is resurfacing as a Red commander at this point makes a lot of sense.

Meanwhile his behaviour make sense for his character: his insistence on his ‘manhood’ and his apparent revolutionary ardour are a defence against the deep pain and vulnerability in him. If his private life really is dead, it haunts him. His fanaticism and cruelty would be a better fit for later in the war, but atrocities occurred this early (though not anywhere near here), often at the hands of non-party Red leaders like Antipov.

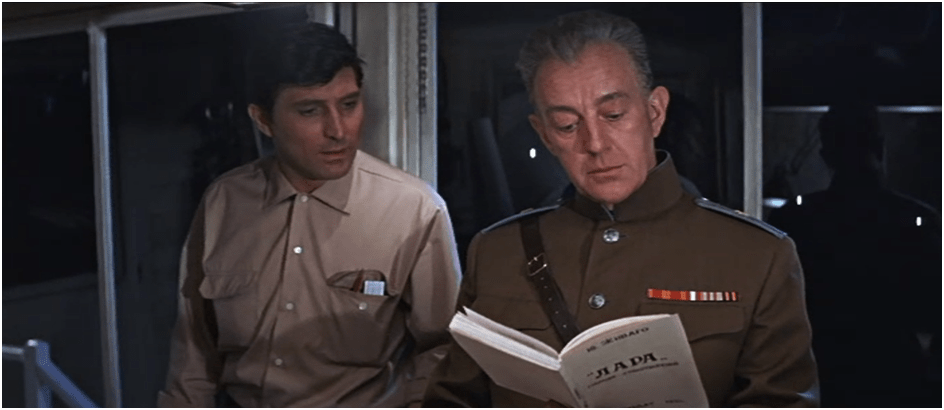

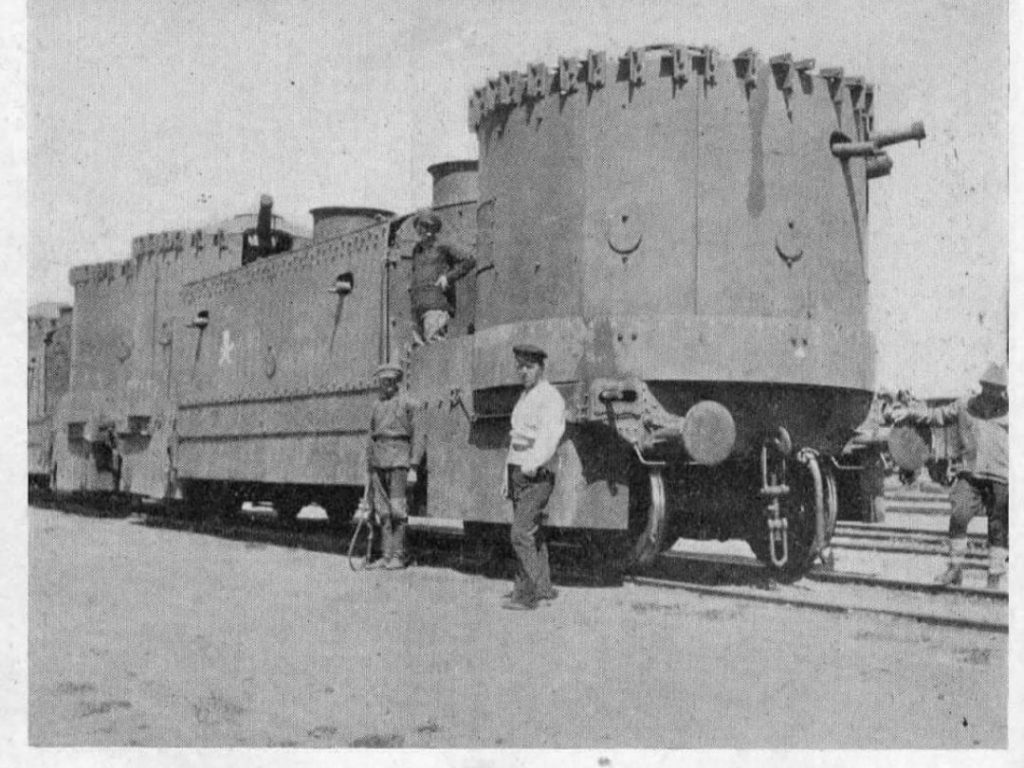

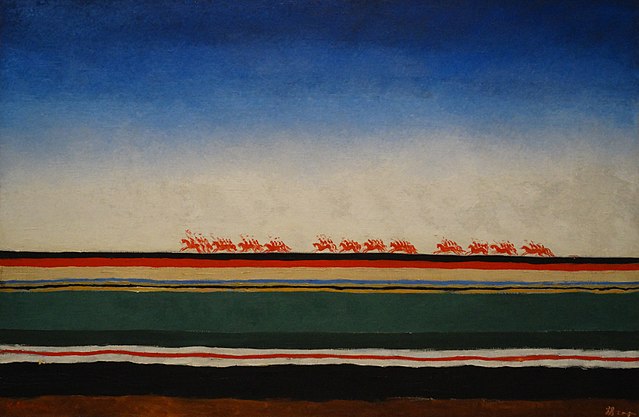

The rest of it does not make sense. On the one hand I’m definitely glad that in the one movie about the Russian Civil War there is an impressive armoured train, staffed by Red Army soldiers in the pointy bogatyrka hats. It would be a shame if that never made it into the vivid colours of mid-century film (likewise with all the cavalry we see later, these are features of the Civil War).

But when we see the armoured train, it’s way too early! It’s the first fine spring day of 1918. It was snowing a few days ago. There are no armoured trains yet. Trotsky’s train first rode out in August 1918 and it was still just a train, no armour yet. Early armoured trains were makeshift; for example one in Turkestan was armoured with compressed bales of cotton.

What about the uniform worn by the Red Army soldiers? It had not yet even been designed. It was formally adopted around January 1919 and it was nearly a year later before most Red soldiers were wearing it.

What’s more, the Red Army itself basically didn’t exist yet. It was a couple of months old, still very small, and entirely concentrated in the west, facing the threat of a renewed war with Germany. The Red Army wasn’t in the Urals at all, anticipating no military threat there (they turned out to be very wrong!).

This isn’t just a pedantic point of chronology. The movie is missing out on the most interesting and important fact: the Red Army just didn’t have its shit together at this stage.

What you would have in this region at this time would be Red Guards. They would be enthusiastic local civilians, say, part of the workforce of a local factory or mine, or a few hundred poor peasants. If the Whites reared their head, local people would flood into the Red Guards to meet the threat. They would do silly things, like abandon the frontline to go home for a hot meal and a change of clothes. But they would not burn a local village because their own houses would be in the village.

Yuriatin

We learn that the town of Yuriatin has changed hands: ‘first the Reds, then the Whites. Now the Reds again.’ Like the pointy hats and armoured trains, this would be plausible a year later but not now. No town in the Urals fell to the Whites before the Czechoslovak Revolt of May 1918.

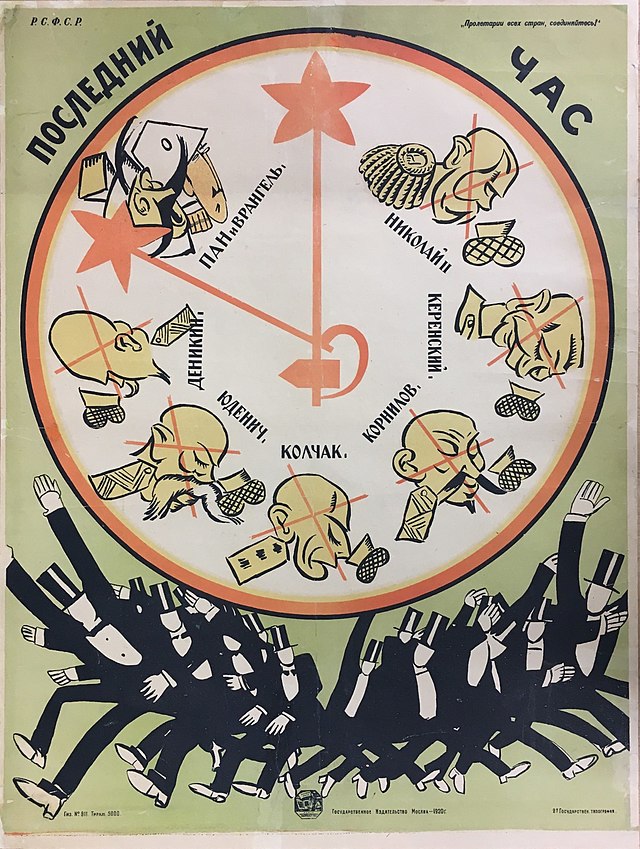

We also learn that there are ‘the Reds in the forest. The partisans’. That’s another example of the movie’s bad habit of mentioning things way too early just because they are going to feature later (White Guards, Bolsheviks and now Partisans). A partisan movement developed across Siberia and the Urals later, after the Whites seized control. This movement really got going after Admiral Kolchak took over all the other White factions in his coup of November 1918 and began to persecute even the moderate socialists who had supported the Whites up to this point.

So that is how the Red partisan movement got started. They have no business mooching around in the woods in early Spring 1918. Who are they partisaning against? It’s like if a movie showed us the French Resistance taking refuge in the woods months before the German invasion of France.

The boarded-up mansion

Yuri’s adopted family have a mansion out here, which the local revolutionary committee has boarded up and declared property of the people. Landlords’ houses were indeed boarded up, to stop criminals from looting the books and fine furnishings and artworks inside (A few examples are given in Eduard Dune’s memoir, Notes of a Red Guard, in the chapter titled ‘Rob the Robbers’). Later the big house might be turned into an artist’s retreat or an orphanage.

Here we get the movie’s only hints at the land revolution. The Varykino estate – the land, tools, livestock and buildings – would have been divided up between local farmers back in autumn. We get a glimpse of this when a local man addresses Yuri’s adopted father as ‘your honour.’ His very likeable response is: ‘Now, now, now. That’s all done with, you know.’

But he is not so easygoing when he sees the house boarded up. Yuri has to warn his adopted father not to tear down the boards. That would be counter-revolution, and ‘they shoot counter-revolutionaries.’ Again, a year later this would be a reasonable. At this point it’s not true and nor would he think it’s true.

Likewise, later we have several claims that deserters from the Red Army are shot. If that were true, the Reds would have run out of bullets and lost the war. They had literally millions of deserters, and the penalty was to lose pension rights on a second offense. Armed mutiny or suspected treason were treated with great harshness but desertion was treated leniently.

The Last Tsar

We can be absolutely sure that it’s still 1918 because that summer, when Yuri and his family are settled nicely in the cottage, bad news comes.

‘Not another purge?’ demands Yuri’s adopted father. This is a very strange thing to say. The first ‘purge’ of the Communist Party took place several years later and consisted of expulsions, not arrests or executions. The script is giving the impression that the Bolsheviks, by summer 1918, have already been through multiple rounds of bloody 1937-style inquisitions.

But no, the bad news is not ‘another’ purge. It’s that Soviet authorities in Yekaterinburg have killed the Tsar and his family. This places us in July 1918.

What doesn’t come across in the scenes of idyllic rural life that frame this news is that over the last three months, in the cut between this sequence and the last, the Russian Civil War has begun and escalated wildly, and the Urals are ground zero. Those Red Guards drawn from the local mine or factory would have been swept aside by professional soldiers – detachments of the Czechoslovak Legion, bands of officers and Cossacks. Those who could not escape westward to friendly territory would become partisans or be killed. The revolutionary committee down in Yuriatin who boarded up the estate are likely most of them dead. You would expect the Whites, on taking Yuriatin in June or July, to have come up to the estate of Varykino and restored to its previous owners full possession of the mansion and its lands. At the very least Yuri’s family should have some soldiers billeted on them; they are at the front line, on a piece of ground that will change hands four or five times between now and mid-1919 when Yuri is abducted by the partisans.

So we don’t see war when we should, and we do see it when we shouldn’t.

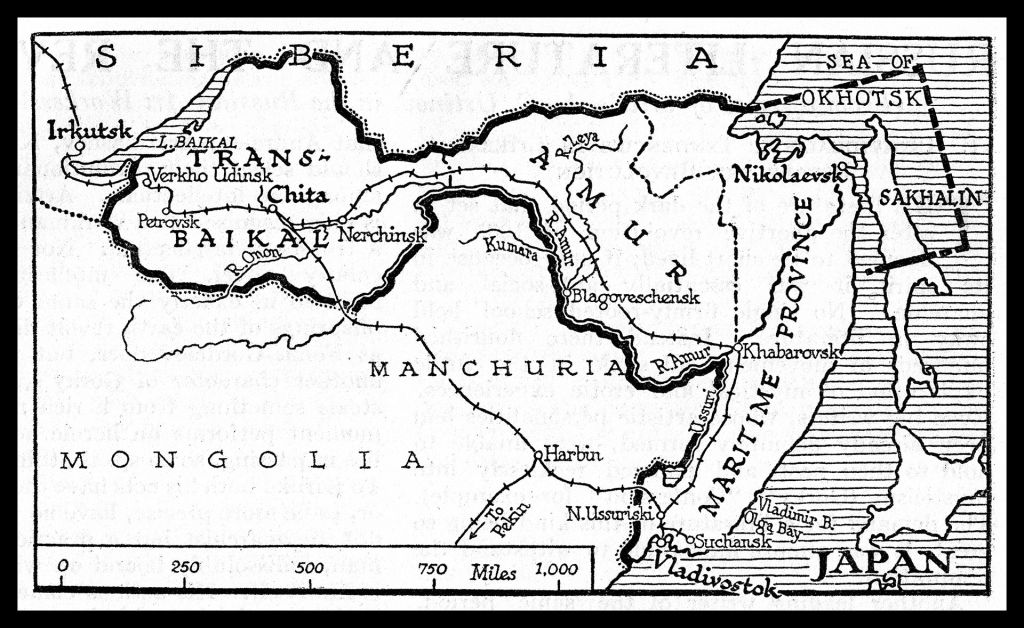

Incidentally, we also hear that Strelnikov has gone to Manchuria. I don’t know why would have gone there, but if he has, he’s a dead man. It’s wall-to-wall White émigrés and Allied agents in Manchuria, and the most violent and depraved White warlords control the territory between here and there.

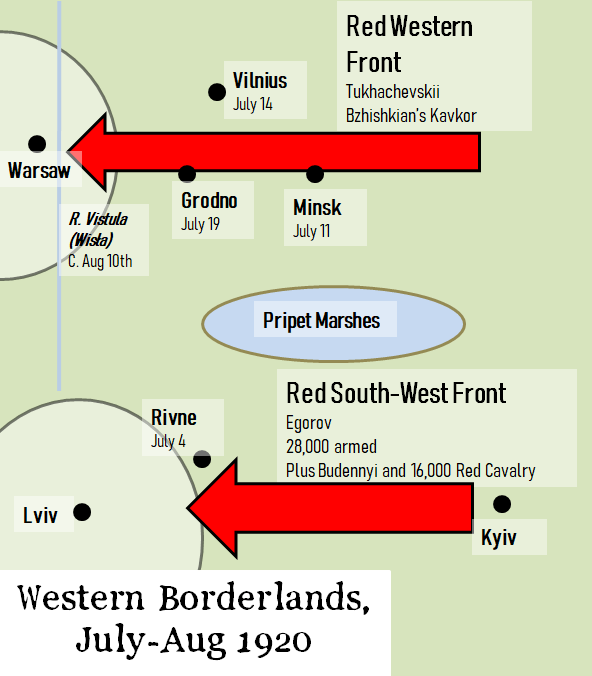

Where are all the counter-revolutionaries?

Yuri is forced to serve as a doctor in a partisan unit for, by my reckoning, a year and a half, from summer 1919 to the winter of 1920-21. The timeline starts to make some sense. We see a charge across ice in late 1919; I’m not sure of the tactics on display here but really anything goes, because nobody really knew what they were doing in the Russian Civil War. Anyway, this might be the crossing of the Irtysh river in November. After forcing the river the Reds took Omsk, capital of the ‘Supreme Ruler’ Admiral Kolchak. After that comes the Ice March, a long period of pursuit and mopping up. Then comes a long war against Ataman Semyonov and other warlords of the Far East, which drags on into 1922 (when the Reds take Vladivostok) and even 1923 (when the last White army is defeated). The various things we see in this sequence with the partisans could well be taking place during these lengthy, confused and far-flung campaigns.

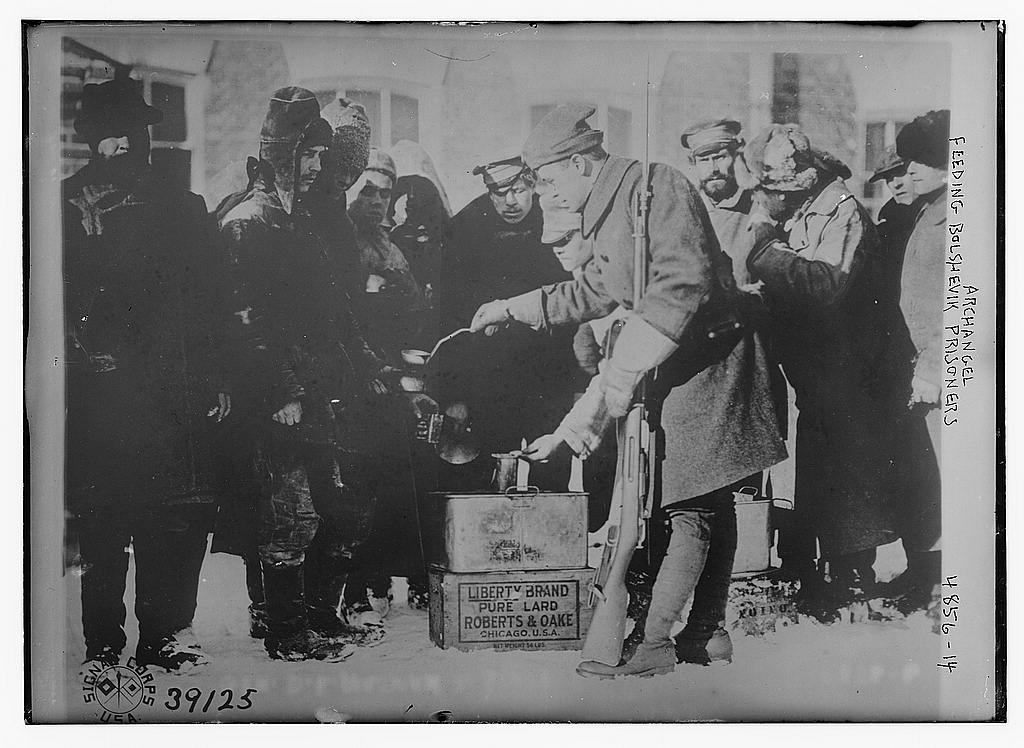

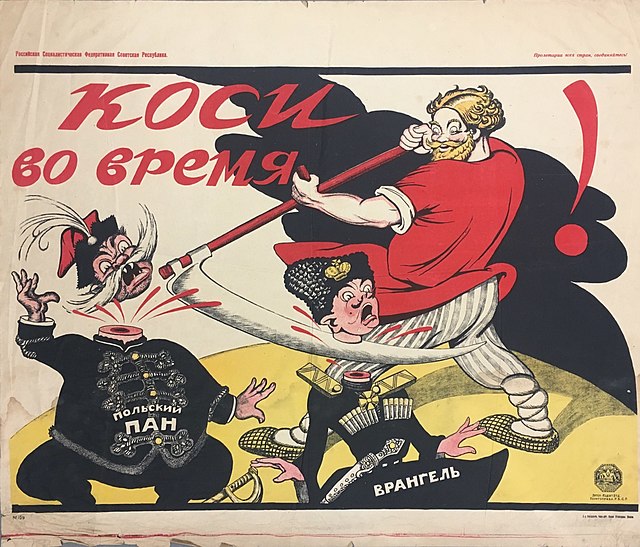

A major problem with this movie is that we don’t properly see a single White Guard in all its three hours. People opposed to the Revolution are phantoms off-screen. In this sequence, White Guards are rifle flashes in the treeline, distant fleeing figures, corpses. There is no indication of who the Whites are, what kind of threat they pose or to whom, or what they are fighting for.

The only time we see White Guards, it is a pathetic showing. They are a few dozen of what appear to be military cadets, young smooth-cheeked men in white uniforms. They are quickly mown down with machinegun fire, after which the Yuri and the Reds inspect the bodies with looks of mingled pity and disgust.

The Red commander glares at the dead body of the White leader, a stuffy-looking officer, and growls, ‘The old bastard.’ This old-school Tsarist martinet has brought these kids on a hopeless crusade and gotten them all killed for nothing.

Presumably these are graduates of some military school set up under Kolchak. Kolchak’s officers did have a bad habit of sending raw recruits into hopeless offensives. In itself this scene is a fair comment on the White cause.

The problem is that it’s all we see. The Whites come across as small bands of foolish adventurers who don’t pose any real threat. In reality the Whites controlled three-quarters of the territory of Russia from mid-1918 to the end of 1919, and held onto sizeable chunks of it for years after. On the second anniversary of the October Revolution, their forces were simultaneously in the suburbs of Petrograd and at Orel on the road to Moscow. On two major fronts they massed over 100,000 fighters each, plus tens of thousands on most of the smaller fronts. They far outclassed the Reds in military expertise, and, thanks to the Allies, had parity or superiority in munitions and supplies. They also had the Allies themselves: several hundred thousand soldiers, sailors and pilots of the intervention. These White governments were repressive, violent and anti-Semitic. And they really had the potential to win the war.

When you know this context, it’s easier to understand why the Reds we see in the movie are a bit uptight. But it becomes less easy to understand why Razin, the partisans’ commissar, seems to think his job is to scour all of Russia punishing ‘dubious poets’ and ‘unreliable schoolmasters.’ No. That’s not the partisans’ job. Their job is to fight behind the lines of a brutal military dictatorship supported by the most powerful countries in the world.

By the way, Razin is another one to add to our collection of Reds who are offended by poetry.

What is missing from this movie? There really should be a scene in which Yuri meets a plastered Cossack pogromist with earrings and a wild forelock, and a necklace made of gold teeth; or maybe a twenty-year-old who commands five thousand men, attends séances, wears the skin of a wolf, and snorts cocaine from the scalp of a murdered commissar. That would give a slightly exaggerated but reasonable impression of what the Whites were all about.

The war’s end

Yuri deserts from the partisans. He limps through a snowy landscape, pursuing huddled indistinct shapes which he imagines to be his wife and child. This captures the misery, confusion, exhaustion and dislocation of this moment in history, the winter of 1920-21. It was ‘Russia in the shadows,’ as HG Wells put it, the young Soviet Union bled white and traumatised from seven years of total war.

Yuri finds his family gone, but Lara is still around, and they shack up together. Komarovsky puts in an appearance, warning them that they are about to be arrested and shot and offering to protect them. Their ‘days are numbered.’

But why? Lara because she is the wife of Antipov/ Strelnikov, who has fallen foul of the Soviet regime for unspecified reasons; Yuri because of his ‘way of life’ – here we go again – ‘everything you say, your published writings, are flagrantly subversive.’ I thought his writings were individualistic, not subversive. And anyway, what has Yuri published in the last two years while riding around Siberia treating gunshot wounds and typhus?

By the end of the war the cycles of violence had taken many spins around and the Soviet security organs had developed harsh instincts. Since mid-1918 the Cheka and the revolutionary tribunals have shot tens of thousands of people, at a low estimate. So in one sense Yuri and Lara are right to be afraid and the film’s tone of doom and dread is not out of place.

But either Komarovsky is bullshitting them or the movie is bullshitting us. Lara has been estranged from Antipov since the outbreak of the First World War; I don’t think she would be on the radar of the authorities. And although many things have changed since early 1918 (a de facto one-party state, an all-consuming total war, years of hunger and epidemics) I feel the Soviet authorities would still really, really not care about Yuri’s poetry. He has never lifted a finger against the Soviet regime. His ‘way of life’ has consisted for the last two years of serving as ‘a good comrade [and] a good medical officer’ in a partisan unit behind enemy lines.

But Yuri and Lara believe that their heads are on the block. Lara and her two daughters, one a child and one unborn, go with Komarovsky. Yuri takes his chances with the Cheka, though they never do come for him, except in the form of Yevgraf who saves him from sleeping rough in Moscow.

Back to the framing device

Meanwhile back in the future, Yevgraf and his niece Tanya have been talking all night, piecing together the story we have just witnessed. Now they finish the last few pieces of the puzzle. They do so very well as far as story is concerned. Not so much the history. Tanya (Yuri and Lara’s daughter) was ‘Lost at the age of eight when Civil War broke out in the Far East.’ She was born in 1921, so this would be 1929 or 1930. There was a brief Sino-Soviet War in 1929, but no Far East Civil War.

Yuri’s death rings true. Many who lived intense lives during the Revolution and Civil War succumbed to illnesses in the decade after.BOf course, there were epidemics and a shortage of medical supplies. But there was also a physical and spiritual exhaustion, which is what does for Yuri in the end.

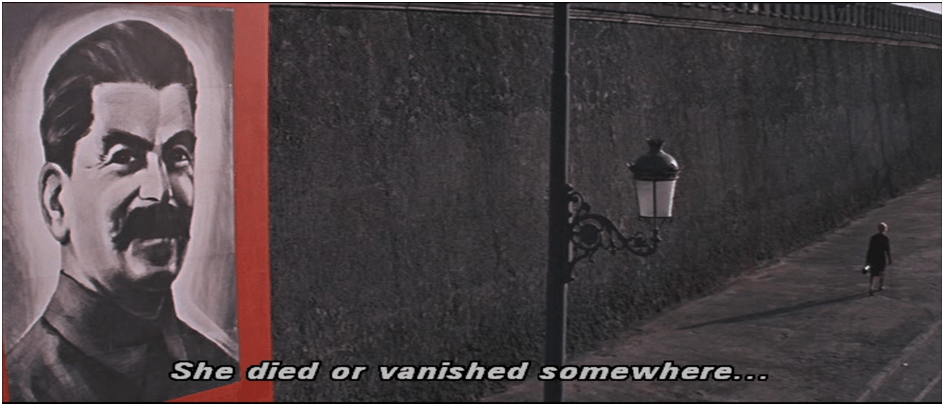

Lara, meanwhile, ‘died or vanished somewhere. In a labour camp […] A nameless number on a list that was afterwards mislaid.’ The arrest of Lara appears to happen in the early 1930s, so before the 1936-9 terror. But it is still all too authentic. The population of prison camps run by the successors of the Cheka grew from 8,500 to two million in a few short years as the Stalin regime tightened its grip.

For all that, the film ends on an optimistic tone. Tanya plays the balalaika as her grandmother did, and her boyfriend seems kind, and rainbows grace the rushing waters by the dam.

And I’ll leave it there, at the end of the movie. I had a conclusion here but it ran on too long. I’ll finish and post that next week.

Meanwhile, if you want to read more about the Russian Civil War according to yours truly, check out my series Revolution Under Siege:

Revolution Under Siege