Listen to this series on Youtube or in podcast form

The Fall of Kazan (5 to 7 August)

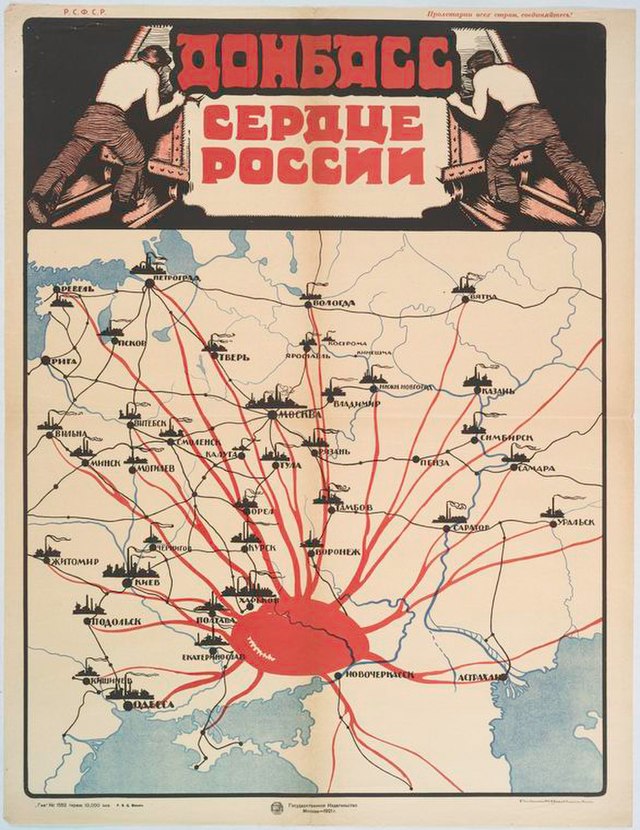

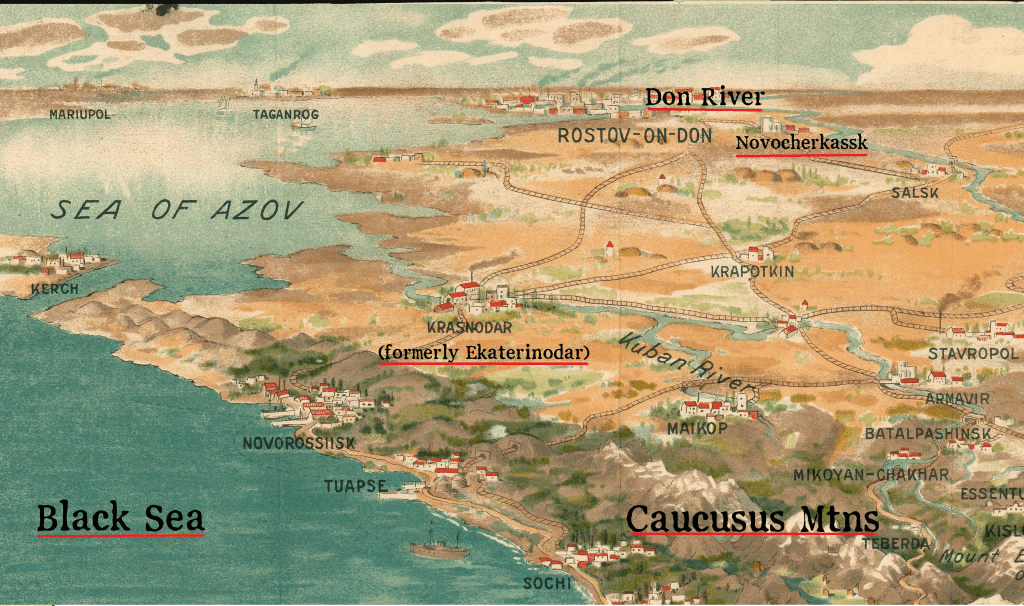

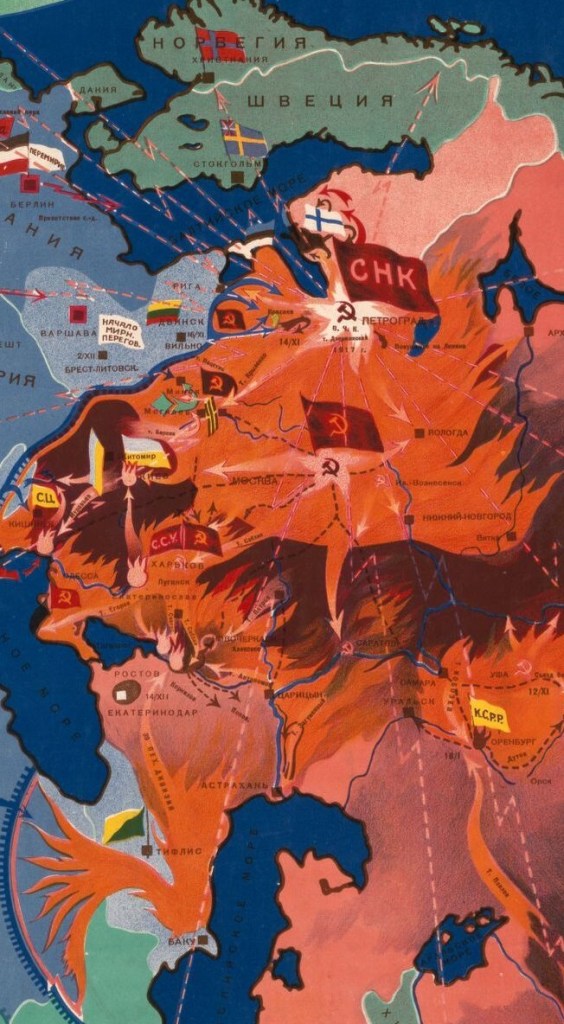

Looking out from revolutionary Moscow to each point of the compass in August 1918, the prospect ranged from threatening to dire. In Part 7 we saw how the Don Cossack revolt was battering at Tsaritsyn and Voronezh. Tsaritsyn lay on the steep right bank of the Volga river. On the left bank of the same river, but eight hundred kilometres north, lies the city of Kazan.

Kazan is the thousand-year-old capital of the Tatars, with a mosque-dotted skyline and a Kremlin of white limestone. It was the site of key battles in Russia’s history.

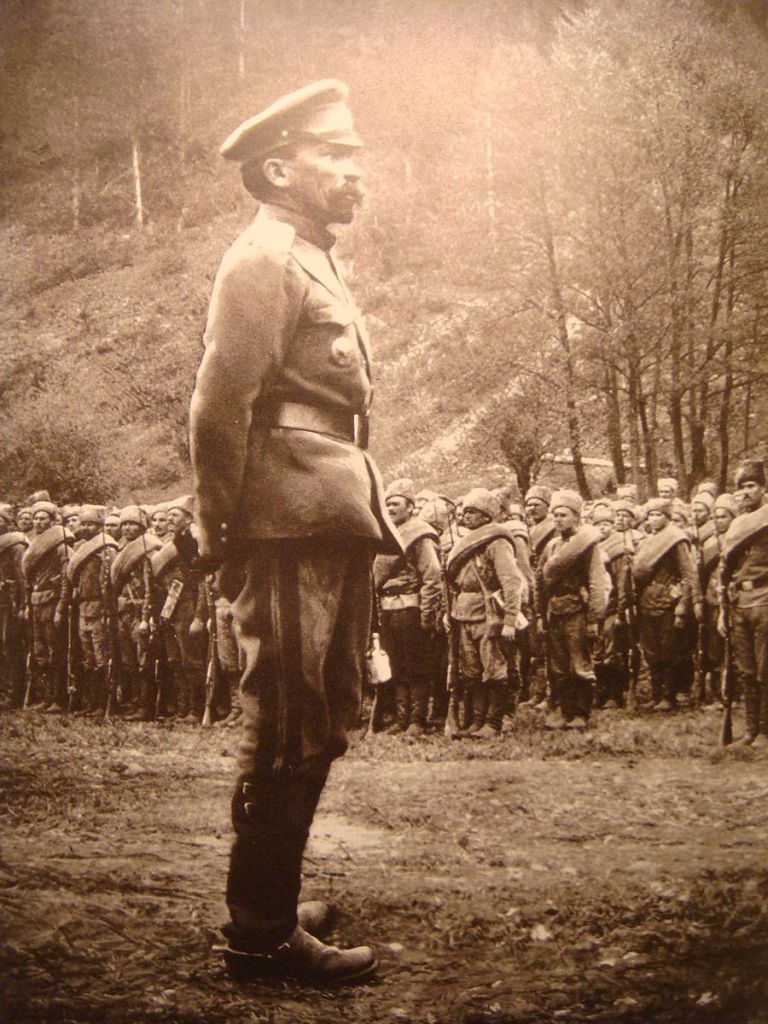

From the city, Jukums Vacietis commanded the Red Army Group on the Eastern Front. Vacietis was the former commander of Latvian Rifles. Though he was himself a Left SR, he had put down the revolt in Moscow, and it had been his idea to fire shells at short range into the Left SR stronghold, harming no-one but shattering the morale of the insurgents. No sooner had the dust settled in Moscow than Murav’ev, defender of Petrograd and conqueror of Kiev, rose up on the Volga with the intention of leading Red and White alike against Germany. Vacietis had taken over in Kazan after the failure of this Murav’ev mutiny. But the staff in his new HQ were leftovers from the Murav’ev days, and in spite of the energy and enthusiasm for which he was known, he faced a steep challenge in trying to get the Red Army organised.

Vacietis was tasked with resisting Komuch, the Right SR-dominated regime which claimed the democratic mandate of the Constituent Assembly. Twelve million people inhabited the food-rich territory on which Komuch carried out its experiment in Democratic Counter-Revolution. This territory was growing thanks to the victories of the People’s Army and the Czech Legion. Beyond Komuch – the officers’ government at Omsk, the warlords of Siberia and the Trans-Baikal, the Japanese occupation force. From the Volga to the Pacific counter-revolution was in the saddle.

Many local Soviets had given up without a fight. Some Red Guard units had immortalised themselves with heroic – but in the short term futile – martial deeds; others had fled or deserted or fallen to pieces.

By August the Soviet government was turning its attention to this Eastern Front. Around 30,000 soldiers were transferred from the west to the Volga in a few weeks over that late summer, a dangerous gamble seeing as Germany might yet attack in the West. They were explicitly threatening to do so; if the Reds failed to deal with the Whites, Germany would invade and deal with both.

It was decided to send out the war commissar Trotsky by train. After scrounging around the chaos and shortages of Moscow to procure a train and supplies, he set off on August 7th. The day before he had sent a dispatch ahead of him:

Any representative of the Soviet power who leaves his post at a moment of military danger without having done all he could to defend every inch of Soviet territory is a traitor. Treachery in wartime is punished with death.[i]

But by the time this message arrived in Kazan, the city was already under attack. There was fighting in the streets, and many representatives of the Soviet power had already left their posts – or worse.

A month to the day after his battle in the streets of Moscow, Vacietis was directing a desperate battle, first outside Kazan on the riverbank and then on the streets of the city itself.

The People’s Army and the Czechs had launched a lightning attack on the city of Kazan on August 5th. The officers who led this assault were doing so in defiance of direct orders from Komuch and from the Czech top brass, who had a more cautious policy. But the officers reasoned that ‘Victors are not court-martialled.’ They brought up heavy guns on tugs and barges and forced a landing with a ‘microscopic force’ of only 2,500. They failed on the first attempt, then got a foothold. The following day, the 6th, they broke through to the streets, and there was heavy fighting in Kazan itself.[ii] One Latvian unit held off the enemy time after time with ‘self-sacrifice and heroic courage, regardless of heavy losses in dead and wounded.’[iii]

But the local Red Guards were poorly-disciplined, could not shoot well, could not build barricades. The staff officers, friends of the late Murav’ev, deserted Vacietis and went over to the enemy. The Red commander ended up trapped in his own HQ, under fire. He barely escaped with his life – the enemy entering his HQ even as he was going out the back door – fighting his way out of the city and fleeing across the river with a few dozen riflemen.

It was the same old story. In the months after October 1917, a few thousand sailors and Red Guards had gone out on the railways and conquered all of Russia. But the challenge was much greater now. Factory workers were up against crack detachments made up entirely of officers. Whenever some Red units made a bold and professional stand, they would be undermined by mass panic and treachery in other units.

By the morning of the 7th, Kazan had fallen to the Whites. The local bishop and the staff and students of the university joined in the counter-revolution wholeheartedly. Komuch seized half of Russia’s gold reserves from Kazan’s vaults, worth 700 million roubles.

Men with weapons and white armbands conducted house-to-house searches, killing ‘Bolsheviks’ on the spot. Red prisoners were torn apart by a ‘well-dressed mob.’ ‘Young women slapped them and spat in their eyes.’ ‘For several days the streets were strewn with disfigured, undressed corpses.’[iv]

Resistance at Sviyazhsk (8 to 28 August)

The stiff resistance of the Latvian Rifles had bought a few hours. This proved significant. Some Red units regrouped at the nearby town of Sviyazhsk, and when the Whites tried to seize the town’s railway bridge, the Reds held on and drove them back.

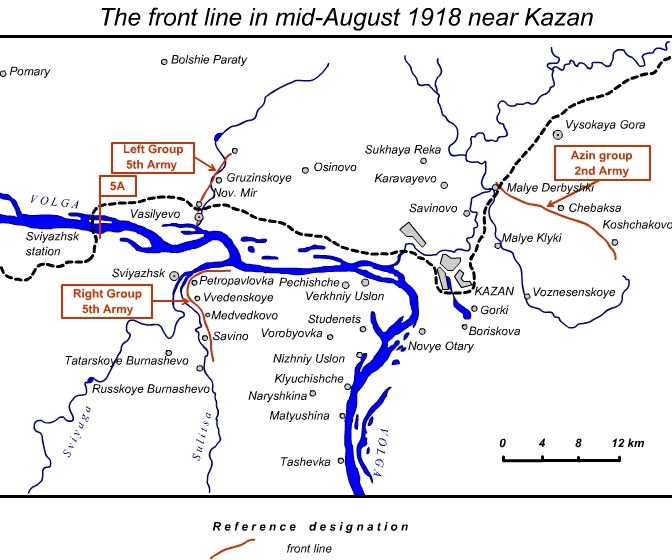

The Reds numbered around ten thousand, holding on around Sviyazhsk in ‘a line of pathetic, hastily-dug trenches,’[v] defending the Romanov railway bridge and barring further advance from Kazan. Effectively, Kazan and Sviyazhsk faced each other from either end, and from opposite banks of, a twenty-kilometre stretch of water. The Red force at Sviyazhsk was the Fifth Army, forming part of Eastern Army Group.

Sviyazhsk was a rustic settlement scattered for some distance along the right bank of the river. It lay twenty to thirty kilometres west of Kazan and it was the first stop on the line to Moscow. Its railway station commanded the bridge.

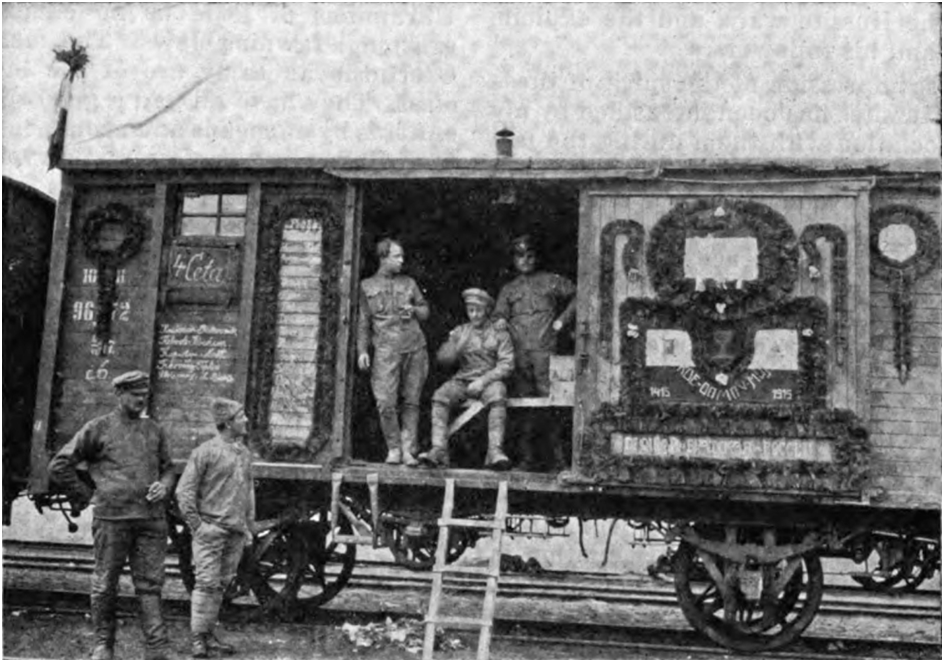

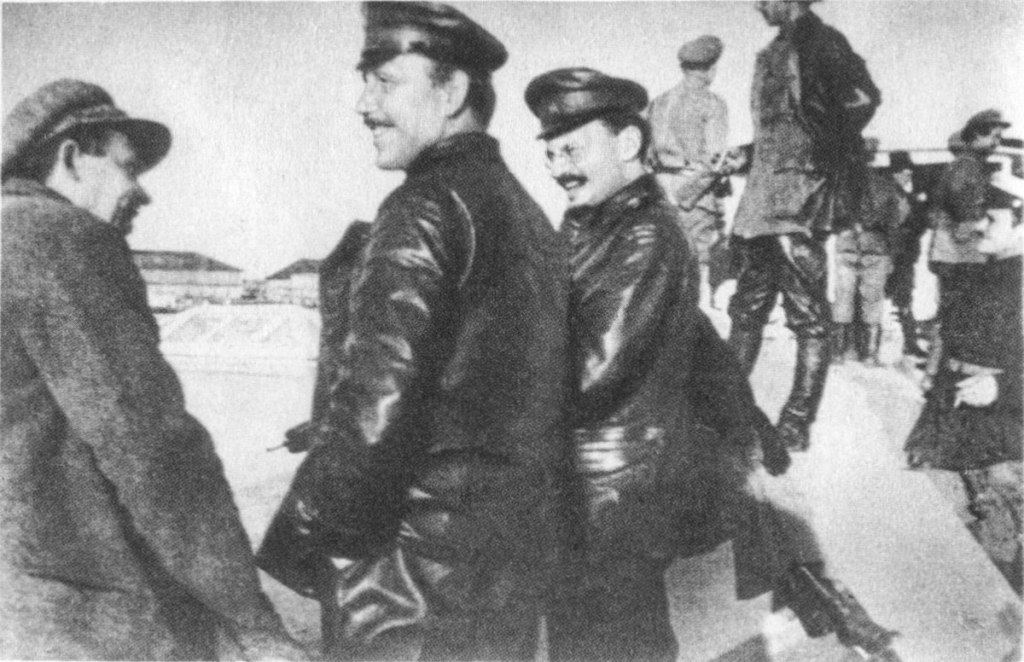

It was at this small railway station that Trotsky arrived from Moscow. Film footage of his arrival shows no great ceremony or dramatic speech – simply an awkward muddle as a man standing next to the War Commissar tries and fails to find some important document or other.[vi]

The locomotive detached and drove away from Trotsky’s train – a signal that he was here to stay. The carriages remained in the railway yard, turning into offices and depots. A second train arrived from Moscow – this one carrying 300 cavalry, an aeroplane, a mobile garage for five cars, a radio-telegraph office and a print shop.

Vacietis made a hand-over to Trotsky, and left to assume overall command of the front.

Conditions were grim. Larissa Reissner, a writer and Red Army soldier, described the defenders of Sviyazhsk ‘sleeping on the floors of the station house, in dirty huts filled with straw and broken glass.’ The Red Army soldier was ‘a human being in a torn military coat, civilian hat, and boots with toes protruding.’ It was a rainy month. Kazan kept up the pressure. ‘Planes came and went, dropping their bombs on the station and the railway cars; machine guns with their repulsive barking and the calm syllables of artillery, drew nigh and then withdrew again.’[viii]

A company of Communists from Moscow who had arrived by train with Trotsky barely knew how to handle their rifles, but fought bravely. On the other extreme was a Latvian unit, hardened veterans, but shattered by the defeat at Kazan and angry at the lack of basic supplies. They threatened mutiny. Trotsky immediately had their officer put up in front of a tribunal and imprisoned.

Nature of the Red Army

We are already acquainted, from previous posts in this series, with the kind of people who made this stand at Sviyazhsk.

34,000 of the 50,000 Red Guards had been incorporated into the new Red Army, along with volunteers who were former soldiers. The all-volunteer Red Army numbered 300,000 in May 1918, but it is likely that only a minority actually had weapons. The others remained in the rear performing auxiliary duties. At first a Red Army soldier needed a reference from a trade union or left-wing political party to join. But from June, the Soviet government brought in conscription in response to mass desertion and to the military crisis.

We are fighting for the greatest good of mankind, for the rebirth of the entire human race, for its emancipation from oppression, from ignorance, from slavery. And everything that stands in our way must be swept aside. We do not want civil strife, blood, wounds! We are ready to join fraternally in a common life with all our worst enemies. If the bourgeoisie of Kazan were to come back today to the rich mansions that they abandoned in cowardly fashion, and were to say: ‘Well, comrade workers’ – or if the landlords were to say: ‘Well, comrade peasants, in past centuries and decades our fathers and grandfathers and we ourselves oppressed, robbed and coerced your grandfathers and your fathers and yourselves, but now we extend a brotherly hand to you: let us instead work together as a team, sharing the fruits of our labor like brothers’

– then I think that, in that case, I could say, on your behalf: ‘Messrs landlords, Messrs bourgeois, feel free to come back, a table will be laid for you, as for all our friends! If you don’t want civil war, if you want to live with us like brothers, then please do … But if you want to rule once more over the working class, to take back the factories – then we will show you an iron fist, and we will give the mansions you deserted to the poor, the workers and oppressed people of Kazan…[xix]

This is the second-last main narrative post in Season One of Revolution Under Siege, a series about the Russian Civil War. Catch you again in two or three weeks’ time for the conclusion; in the meantime there will be smaller side-posts and a podcast version of this episode. Thanks for reading.

‘to settle the question whether homes, palaces, cities, the sun and the heavens are to belong to the working people, to the workers the peasants, the poor, or to the bourgeois and the landlords […] I am today eating an eighth of a pound of bread, and tomorrow I shall not have even that, but I shall just tighten my belt, and I tell you plainly – I have taken power, and this power I shall never surrender!’

And then there were Red partisan units, armed bands of poor peasants led by local charismatic leaders. One Red commander on the Northern Front described how difficult it was to incorporate them into the Red Army:

We certainly had a lot of trouble with them at the front. They often upset all our plans and arrangements; they never conformed to any general scheme, but just trusted to their own inspiration. The “Wolf Pack” band did specially good work; it was commanded by a sailor, and consisted entirely of sailors, soldiers and workmen. An anarchist band also distinguished itself; it was not a particularly large one-barely two hundred men, but a very compact body, firmly knit together by the reckless courage of all its members.[ix]

So the defenders of Sviyazhsk would have been a mix of former Red Guards; veterans of the Great War; adventurous guerrillas of the ‘Wolf Pack’ variety; and new peasant conscripts. In addition, thousands of communists answered an appeal and joined the army.

One in every twenty-five Red Army soldiers was an international volunteer; Reissner even mentions Czechs in the Red camp at Sviyazhsk, fighting against their own countrymen on the opposite bank. Many wore their own national army’s uniform, in defiance of orders. There was a good reason for this, a reason which many conscripts discovered to their cost. Some conscripts showed up for enlistment dressed in their worst clothes, assuming that they would trade them in for a uniform. But the Red Army had no uniforms! So they had to go to war in the most threadbare and ill-fitting garments they owned. They wore a red badge with a hammer-and-plough device, or an upside-down red star; apart from that, it was impossible to tell who was Red and who was White.

There were sixty different makes of artillery in Red service during the war, and thirty-five different varieties of rifle from American Springfields to Japanese Arisakas. No doubt some of the same variety was on display at Sviyazhsk.[x] You can easily imagine the mess caused by incompatible ammunition, parts, or training.

There was no formal organisational structure and there were no training centres. All army ranks had been abolished; ‘commander’ was a post held, not a title or a distinction. Outside of the military sphere, in day-to-day life, subordination of lower ranks to higher was not allowed. Some years later, one private got his commander into deep trouble by polishing his boots. Erich Wollenberg writes that the commander was accused of acting in an aristocratic spirit. He was let off the hook when it became clear that the private had been acting on his own initiative.

The commanders were drawn from three main sources. First, and well in evidence during the struggle for Kazan, were the military cadres. These were communists who had infiltrated the old Tsarist army during 1917. After the October Revolution they had to make the switch from dissidents in the old army to leaders of a new army. They had enough humility to stay in their lane and defer to actual trained soldiers on military matters.

Second, former corporals and sergeants of the old army. (Some, like Kliment Voroshilov in the South, commanded whole armies). In general these former Non-Commissioned Officcers – numbering around 130,000 – lacked the humility of the military cadres, and considered themselves superior to the commissioned officers. Sometimes they were right about this and sometimes they were wrong. In other words, the tsarist officer was known by the red board on his shoulder; the former NCO was known for the chip on his shoulder.

Third, around 22,000 former officers had been brought into the Red Army by this point. Some were revolutionaries, like Tukhachevsky. Others were conscientious public servants and patriots who believed, as we have seen in Part 7, that ‘the people are not mistaken.’ Many were conscripts, working under compulsion. Some were simply waiting for the chance to betray their men to the Whites. Years later, Trotsky was poring over memories from the struggle for Kazan when he realised that a particular artillery officer at Sviyazhsk had been trying to kill him.

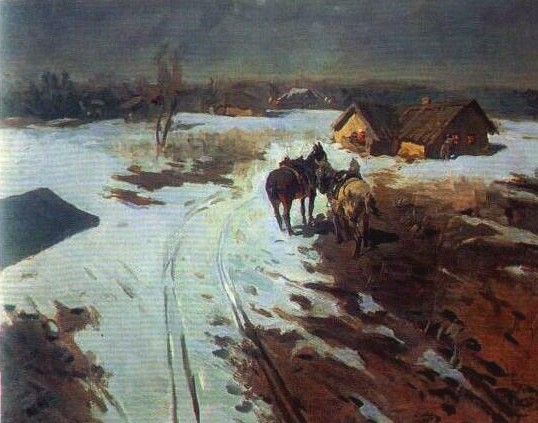

Red Cohesion

The scene of Red soldiers enduring shellfire and rain on a dreary riverbank in early autumn has not been deemed worthy of a dramatic military painting by any artist. This is understandable. But day by day something momentous was happening. According to one historian, these were ‘operations which we may with hindsight deem to have been key to the eventual outcome of the civil wars.’[xi] According to another, the moment of the struggle for Kazan was one of two at which the existence of the Soviet state hung in the balance.[xii]

Behind and around the Reds at Sviyazhsk, tens of thousands of soldiers were being drawn up and prepared for a counter-attack on Kazan. This took time, especially in the chaotic conditions of Russia in 1918. If Sviyazhsk did not hold, this concentration of forces could not take place, and there was little hope of recovering Kazan. If the Red Army could not concentrate its forces and take Kazan, then what use was it? For the Reds, there had been no significant victories since the start of full-scale civil war. If Sviyazhsk, the Fifth Army and Eastern Army Group had been shattered, the damage to morale might have constituted a death-blow to the revolution.

This was not a straight battle but a test of cohesion. Red forces had broken and fled countless times since the Czechoslovak revolt. What was to stop them breaking again, under daily attack and with poor supplies?

The old Tsarist army had held together under fire through drill and traditional hierarchies and violent disciplinary measures. The new Red Army needed a new kind of cohesion.

Over the month of August, through trial and error and through will, the Red Army found ways and means. In small ways at first, they began to cohere.

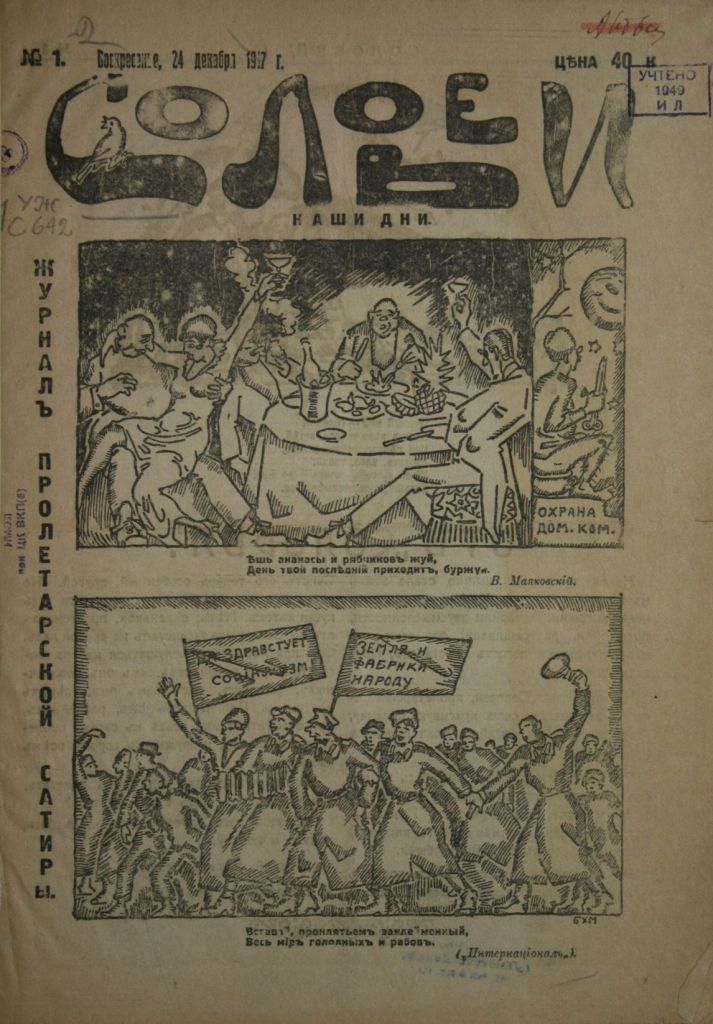

The train carriages from Moscow got to work. Boots and food started to arrive. Reinforcements came – from tiny bands to large regular units. Telephone and telegraph wires were strung out across the countryside. Order began making its first inroads against chaos. The war commissar’s carriage was in the station, and he himself was touring the river-bank under enemy shells. Political newspapers improved morale, linked the dreary riverbank to the world revolution.

It must have had an impact on a conscripted krasnoarmeyets (Red Army member) from a village background to share trenches and cheap cigarettes and long discussions with workers from the towns, with communists and anarchists and SRs, veterans of the revolutionary storm of 1917 or even of underground and exile; people who had fought as Red Guards or partisans in the struggles of early 1918.

The Baltic sailors arrived, the shock troops of 1917 in their military vessels, straight from the sea to the Volga via the Mariinsky canal system. Artillery skirmishes between Red and White flotillas took place three or four times a day on the Volga. To the immense satisfaction of the Red soldiers, the White vessels were driven back.

A small airfield was set up, and an anarchist pilot named Akashev put in charge of scouting from the air and dropping bombs into Kazan. White planes were now being answered by Red, and this gave heart to the defenders of Sviyazhsk.

Morale was improving. But it was still shaky. Every day saw attacks on Sviyazhsk or other positions. From time to time units would abandon their positions, break under fire, refuse to follow orders.

But another factor in Red cohesion at Sviyazhsk was indicated by Trotsky’s order of August 14th:

It has been reported to me that the Petrograd guerrilla detachment has abandoned its position…

The soldiers of the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army are neither cowards nor scoundrels. They want to fight for the freedom and happiness of the working people. If they retreat or fight poorly, their commanders and commissars are to blame.

I issue this warning: if any unit retreats without orders, the first to be shot will be the commissar, and the next the commander.

Soldiers who show courage will be rewarded for their services and promoted to posts of command.

Cowards, self-seekers and traitors will not escape the bullet.

For this I vouch before the whole Red Army.

Raids (28-30 August)

The attack on Kazan by the White forces had been a brilliant and daring exploit. But weeks had passed and no further progress had been made. Every day the Reds grew stronger. From the point of view of the Whites, another daring operation was called for.

Raid by Land

On August 28th 2,000 White Guards crossed the river under cover of darkness. They made a wide circle around the Red lines. After an exhausting forced march, they arrived at a railway station behind Sviyazhsk, killed its small garrison to a man, and left it in ruins. They cut the railway line to Moscow.

An armoured train with naval guns was sent out from Sviyazhsk to intercept the Whites. But the Whites took it and burned it, and its remains lay by the roadside only a kilometre or two from town, a visible warning. The Whites advanced on the Sviyazhsk railway station and on the key bridge next to it.

The front was under pressure and shaky; Trotsky could only spare two or three companies to turn and face the White infiltrators. To compensate, he emptied the train of every one of its personnel: clerks, wireless operators and cooks. They were armed and sent out one kilometre to block the White advance.

Reissner describes the eight-hour battle which ensued:

The staff offices stood deserted; there was no “rear” any longer. Everything was thrown against the Whites who had rolled almost flush to the station. From Shikhrana to the first houses of Svyazhsk the entire road was churned up by shells, covered with dead horses, abandoned weapons and empty cartridge shells. The closer to Svyazhsk, all the greater the havoc. The advance of the Whites was halted only after they had leaped over the gigantic charred skeleton of the armored train, still smoking and smelling of molten metal. The advance surges to the very threshold, then rolls back boiling like a receding wave only to fling itself once more against the hastily mobilized reserves of Svyazhsk. Here both sides stand facing each other for several hours, here are many dead.

The Whites then decided that they had before them a fresh and well organized division of whose existence even their intelligence service had remained unaware. Exhausted from their 48 hour raid, the soldiers tended to overestimate the strength of the enemy and did not even suspect that opposing them was only a hastily thrown together handful of fighters with no one behind them except Trotsky and Slavin sitting beside a map in a smoke-filled sleepless room of the deserted headquarters in the center of depopulated Svyazhsk where bullets were whistling through the streets.[xiii]

The Whites withdrew. But the Red Army was not just battling against the Whites. It was faced with its own inexperience and the accumulated trauma of a summer’s worth of shattering defeats. One intention of the raid was to damage the Reds’ morale. In this it was not a failure. The raid sent a fresh wave of panic through the Fifth Army.

Mutiny

The 2nd Numerny Petrograd Regiment, a body of 200, broke. This was not a band of peasant conscripts or partisans, but a unit of worker-militants led by commissar Panteleev.[xiv]

Not only did this unit break; led by their commander and commissar, the 200 stormed on board a steamship that lay at anchor on the Volga, hijacked it and set sail.

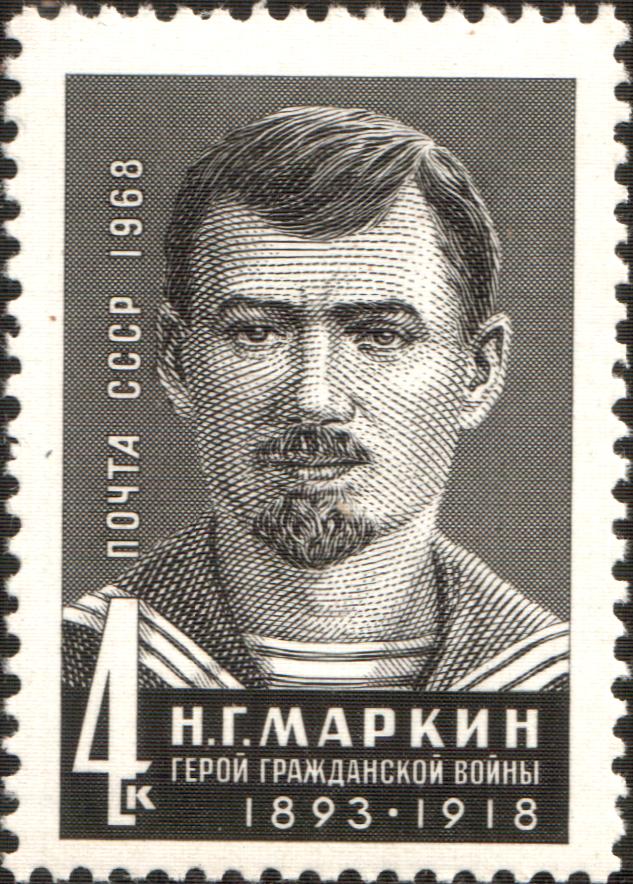

A Bolshevik sailor named Nikolai Markin acted fast.

Boarding an improvised gunboat with a score of tested men, he sailed up to the steamer held by the deserters, and at the point of a gun demanded their surrender. Everything depended on that one moment; a single rifle-shot would have been enough to bring on a catastrophe. But the deserters surrendered without resisting. The steamer docked alongside the pier, the deserters disembarked.[xv]

At once Trotsky assembled a tribunal to pronounce judgement on the Regiment. Its decision was announced on August 30th in Order No 31, authored by the War Commissar:

The brave and honorable soldier cannot give his life twice – for himself and for a deserter. The overwhelming majority of the revolutionary soldiers have long been demanding that traitors be dealt with ruthlessly. The Soviet power has now passed from warning to action. Yesterday twenty deserters were shot, having been sentenced by the field court-martial of the Fifth Army.

The first to go were commanders and commissars who had abandoned the positions entrusted to them. Next, cowardly liars who played sick. Finally, some deserters from among the Red Army men who refused to expiate their crime by taking part in the subsequent struggle.[xvi]

Raid by Water

The Reds took the initiative. That very night there was a daring raid by small Red torpedo-boats on the White flotilla docked at Kazan. Trotsky and the sailors Markin and Raskolnikov were on this raid personally. They came under fire. At one point Trotsky’s boat was separated from the others, disabled by machine-gun bullets, pierced by a shell, lit up by a burning oil-barge, and stuck on a half-sunken enemy vessel. The occupants of the boat thought they were as good as dead.

But the other vessels had already gone into Kazan harbour, where they wrecked the enemy flotilla and destroyed artillery on land. The Whites were in too much chaos even to realise they had a chance to kill the War Commissar, much less to do so.

In the days after the raid, the pilots under the anarchist aviator Akashev brought good news. The Second Red Army, commanded by a Red Cossack, had advanced to within ten or fifteen kilometres of Kazan from the north. In all, 25-30,000 Red soldiers were now closing in on Kazan on both sides of the river. There began an exodus of the wealthier classes, and there was an uprising of workers within the city.

Threats rang out from Red lines: any White who deserted now would be pardoned, but White collaborators could expect confiscation of property, imprisonment or death. Dozens of Whites had already deserted and come over to the Reds. To those who held out in Kazan, ‘Remember Yaroslavl’ was the chilling threat. The Red commanders contemplated, but never carried out, an artillery bombardment of the city.

Meanwhile, the Whites put down the workers’ revolt within Kazan with a massacre.

The Recapture of Kazan (1 to 9 September)

On September 1st news reached Sviyazhsk of the shooting of Lenin (which we mentioned in a previous post, ‘Controversies: Terror’). Trotsky hurried back to Moscow. He was not present when the Fifth Army, after a month at Sviyazhsk, crossed the Volga and made a landing at Kazan. But Reissner was there:

On September 9 late at night the troops were embarked on ships and by morning, around 5:30, the clumsy many-decked transports, convoyed by torpedo boats, moved toward the piers of Kazan. It was strange to sail in moonlit twilight past the half-demolished mill with a green roof, behind which a White battery had been located; past the half-burned Delphin gutted and beached on the deserted shore; past all the familiar river bends, tongues of land, sandbanks and inlets over which from dawn to evening death had walked for so many weeks, clouds of smoke had rolled, and golden sheaves of artillery fire had flared.

[…] yesterday, words of command were restlessly sounding and slim torpedo boats were threading their way through smoke and flames and a rain of steel splinters, their hulls trembling from the compressed impatience of engines and from the recoil of their two-gun batteries which fired once a minute with a sound resembling iron hiccups.

People were firing, scattering away under the hail of down-clattering shells, mopping up the blood on the decks … And now everything is silent; the Volga flows as it has flowed a thousand years ago, as it will flow centuries from now.

We reached the piers without firing a shot. The first flickers of dawn lit up the sky. In the grayish-pink twilight, humped, black, charred phantoms began to appear. Cranes, beams of burned buildings, shattered telegraph poles – all this seemed to have endured endless sorrow and seemed to have lost all capacity for feeling like a tree with twisted withered branches. Death’s kingdom washed by the icy roses of the northern dawn.

And the deserted guns with their muzzles uplifted resemble in the twilight cast down figures, frozen in mute despair, with heads propped up by hands cold and wet with dew.

Fog. People begin shivering from cold and nervous tension; the air is permeated with the odor of machine oil and tarred rope. The gunner’s blue collar turns with the movement of the body viewing in amazement the unpopulated, soundless shore reposing in dead silence.

This is victory.

The Whites had abandoned Kazan. In the face of the Red build-up, they had calculated that they could not hold the city. The advancing Reds found in ‘the courtyard of the prison, a row of fresh corpses: the arrival of the Red cavalry […] had interrupted the executions.’[xvii]

By mid-September, there would be 70,000 fighters of the Red Army on the Eastern Front, throwing back the Czechs and Komuch at all points. In Part 5 we briefly mentioned the workers of Troitsk, Verkhne-Uralsk and Ekaterinburg, who formed a partisan army and made a fifty-day march, in constant battle, out of hostile territory. A few days after the recapture of Kazan, this march came to an end when they linked up with the Third Red Army near Perm.

Almost simultaneous with the fall of Kazan, a Red army under Mikhail Tukhachevsky took Simbirsk from Komuch. This battle saw a series of daring and innovative exploits on the Red side: an unmanned locomotive thundered across an iron bridge through White barricades, followed by a manned and armoured train; Red Army soldiers infiltrated behind enemy lines and organised an uprising of railway workers (Simbirsk, home town of Lenin, is today called Ulyanovsk).

But it is perhaps a mistake to focus on these kinds of spectacular operations. As we have seen, at Kazan itself daring exploits were more a feature of White tactics. Revolutionary élan was in evidence on the Red side, but it was not a new phenomenon. What the Red Army had learned at Kazan was plain professional soldiering. The victory was won not necessarily with reckless death-defying charges, but through stoic endurance. It was a victory of supplies, logistics and politics, all contributing to cohesion. (That is one reason, I suspect, why it has not been deemed worthy of a dramatic painting or of the Mosfilm treatment).[xviii] What happened at Sviyazhsk was the synthesis of the zeal of the commissar and the technique of the specialist.

In their thousands, the people of the re-conquered Kazan attended revolutionary meetings in the streets and in the main theatre, celebrating the victory.

In addition to the sources below, I found this article on the Civil War museum at Sviyazhsk useful and illuminating.

[i] Trotsky, Leon. How the Revolution Armed, ‘The Fight for Kazan,’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1918/military/ch33.htm

[ii] Mawdsley, Evan. The Russian Civil War, p 79-80

[iii] Trotsky, Leon. How the Revolution Armed, ‘The Fight for Kazan,’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1918/military/ch33.htm

[iv] Serge, Year One, p 320

[v] Serge, Year One, p 332

[vi] Axelbank, Herman (dir.), Tsar To Lenin, 1937

[vii] Trotsky, Leon. My Life: An Attempt at an Autobiography, 1930. Chapter 33, ‘A Month at Sviyazhsk.’https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/mylife/ch33.htm

[viii] Reissner, Larissa. ‘Svyazhsk.’ Republished in Fourth International, June 193. https://www.marxists.org/history/etol/newspape/fi/vol04/no06/reissner.htm

[ix] Wollenberg, Erich, The Red Army, Chapter 2

[x] Khvostov, Mikhail. The Russian Civil War (1) The Red Army, p 17

[xi] Smele, The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, 87

[xii] Mawdsley, 268

[xiii] Reissner

[xiv] Service, Robert. Trotsky. Macmillan, 2009. P 221

[xv] Trotsky, My Life https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/mylife/ch33.htm

[xvi] Trotsky, Leon. How the Revolution Armed, ‘The Fight for Kazan,’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1918/military/ch33.htm#baugust24

[xvii] Serge, Year One, p 339

[xviii] Another reason, I suspect, is that it is impossible to erase Trotsky from the events. The closest thing we’ve got is the 2017 Russian TV series Trotsky which presented, in episode 1, a distorted portrayal of the execution of Panteleev and the others. I have written about this lamentable TV series here.

[xix] Trotsky, Leon. How the Revolution Armed, ‘The Fight for Kazan.’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1918/military/ch33.htm#baugust24