If you look up a map of the Russian Civil War, you will see that the Reds were reduced to a small part of Russia. How did that happen? Mostly due to the Czech Revolt.

This post will tell the story of how the Eastern Front of the Russian Civil War blazed up in Spring 1918. The major players were the Allied powers, the Right SRs, the officers and the Cossacks. The biggest part of the heavy lifting, however, was done by an outfit called the Czechoslovak Legion, an improbable but enormously significant presence in Russia in 1918.

THE ALLIES

The first piece of context here is the implacable hatred with which the October Revolution was greeted by the wealthy and powerful in the Allied countries.

All over the world there were many who sympathised with the Revolution – from the IWW in the United States to followers of the late James Connolly in Ireland.

But in politics and media it was a different story. Newspapers reported that all women over the age of eighteen had been made public property; that Lenin, ‘alias Zederblaum’[i] was secretly Jewish, and that he and Trotsky were busy murdering one another in drunken brawls over gambling debts; that Red Guards, who were ‘chiefly Letts [Latvians] and Chinese’, had spent the spring of 1918 gunning down crowds of people in the cities.

The viewpoint of the Allied leaders was distorted; they saw the revolution only through the prism of the war. With the Russians out of the war, they believed, the Germans would soon be in Paris and the Turks on the borders of India. The Russian revolutionaries were referred to as ‘Germano-Bolsheviks.’ Count Mirbach, the German ambassador, was described by the US ambassador as ‘the real dictator of Russia.’ It was taken as a fact that the Bolsheviks were funded by German intelligence and that the Red Guards were led and trained by German officers. The Allied leaders seriously imagined that from the POW camps of Russia would be recruited a new German army, millions strong, armed and equipped from the Allies’ own bloated supply depots in Vladivostok and Murmansk.

Anti-Semitic conspiracy theories were expounded by, among many others, Winston Churchill (to whom the Reds were a ‘strange band of Jewish adventurers’) and the London Times (they were ‘adventurers of German-Jewish blood in German pay’).

Nov 9th 1917. From https://www.germansfromrussiasettlementlocations.org/2017/11/the-bolshevik-revolution-beginning-of.html

Western journalists knew so little about the Bolsheviks that they confused them, perhaps through a clumsy translation, with the SR Maximalists. The Bolsheviks were an open mass party which rejected terrorism and had hundreds of thousands of members; the Maximalists were a conspiratorial terrorist outfit with a membership of one thousand. But even without the translation problems, many in the Allied camp probably would not have known the difference. They behaved as if a few hundred bohemian bomb-throwers had stumbled into power.

Some were, in hindsight, more sensible: the Tory Arthur Balfour reasoned that hostility to the Soviets would push them into the arms of the Germans, while a pragmatic accommodation with the Soviets might deny the Germans resources and the opportunity to redeploy their armies to the west.[i]

But they were up against others whose grasp on reality was less firm: to Lord Robert Cecil the Soviet regime was ‘outside the pale of civilised Europe’ – and it was treated as such: western diplomacy boycotted Moscow.

“Revolt will be short lived”!

Journalists who were actually in Russia in the first half of 1918 tried to convey the reality. Louise Bryant from the US bore witness to a revolution that was remarkable for its clemency and tolerance, that had mass support and that had already made drastic improvements to the lives of workers, women and peasants. On Stockholm on her way out of Russia in early summer, she met ‘a correspondent from one of our biggest press agencies,’ who immediately described the Bolsheviks as ‘scum.’

I felt myself forced to ask one more question. ‘If you had to choose between the Bolsheviki and the Germans, which would you prefer?’

Without hesitating he replied, ‘The Germans.’

‘Have you ever been in Russia?’

‘No.’[iii]

Why were they so hostile? We can dismiss any notion that their hostility was based on a prophetic fear of Stalinist totalitarianism. On the contrary, they denounced ‘anarchy,’ ‘chaos,’ ‘adventurers,’ etc. The picture of Bolshevism in their heads was quite the opposite of the totalitarian caricature. The real reasons were as follows:

- Because the Bolsheviks had pulled Russia out of the war and published the secret treaties between Russia and the Allies. This became especially urgent from Spring 1918, as German forces, reinforced by divisions redeployed from the quiet eastern front, made a devastating offensive, and later Turkey seized Baku.

- Because the revolution had renounced Russia’s debts to the Allied countries and had nationalised foreign-owned industries.

- Because the Bolsheviks had made a socialist revolution, which might inspire the workers to take power in other parts of the world.

THE ALLIES

From the very start, Allied powers supported the White Guards. On December 2nd the British cabinet voted to give money to the counter-revolutionary armies of Alexeev and Kaledin.[ii] On December 23rd, Britain and France did a ‘carve-up’ of their respective spheres of influence in Russia: Britain’s ‘sphere’ corresponded suspiciously to British money invested in the oil of the Caucasus, France’s to French money in Ukrainian coal and iron.

Early on, the Soviets tried to come to an understanding with the Allies. With the ever-present threat of the German military, even after the signing of the Brest-Litovsk treaty, a pragmatic orientation to the Allies made sense. There was cooperation early on, for example in relation to Murmansk – where a British battleship fired a salute to the Red Flag, and an Allied train went to the aid of Red Finns against White Finns.

Some Bolsheviks opposed this cooperation on principle, but Lenin spoke for most when he said, ‘We will accept guns and potatoes from the Anglo-French imperialist bandits.’

The Americans were reluctant to intervene at first. President Wilson believed his democratic peace plan, known as the Fourteen Points, would induce the Russians to rejoin the war, and I read that 30,000 copies of it were pasted up by American agents all over the walls of Petrograd.[iii]

Early on, the Soviet regime planned to have a mass civilian militia instead of a standing army. It was in response to the threat of the German military that the Soviet regime shelved this idea and began, from February, to build the Red Army. The Red Army’s first battles at Pskov and Narva, commemorated annually in Russia and beyond even to the present day, were not against the Whites or the Allies but against the German invasion of late February.

Meanwhile in Ukraine the Red Army fought alongside an Allied force against the Germans. This force was the Czechoslovak Corps or Legion.

A Red commander paid tribute to the Czechs’ fight against the German advance: ‘The revolutionary armies of South Russia [sic] will never forget the brotherly aid which was granted by the Czech Corps in the struggle of the toiling people against the hordes of base imperialism.’[iv]

The Germans were ‘the hordes of base imperialism’! Germano-Bolsheviks indeed.

But the World War was the all-consuming priority. Allied representatives promised aid, if only the Soviets would force their own people back into the trenches. They would not. Allied attitudes hardened.

Russia was meanwhile crawling with Allied military missions, officials and agents, a legacy of the war. By May 1918 this apparatus was busy making links and distributing funds. AJP Taylor writes, ‘they imagined that somewhere in Russia was to be found some group of people who wanted to continue the war.’[iv]

The wealthy, the officers and the professional classes did want to continue the war. They felt humiliated and threatened by the revolution, believed that the fatherland and/or civilisation were about to perish, and still possessed enough wealth, connections, self-confidence and skills to fight back. These people formed leagues, networks, councils, and linked up with foreign powers. Funds were transferred, plans laid, promises made.

At this point the intelligentsia were deeply conflicted about the revolution, symbolised in the split within the SRs. Looking at where the two sides stood in May 1918, it is difficult to imagine that they had ever been in the one party. The Left SRs held high positions in the Soviets, the fledgling Red Army and the Cheka, while the Right SRs were in the various leagues and councils of the underground counter-revolution, shoulder-to-shoulder with Black Hundreds and Tsarist generals.[v] In that milieu they nursed their grudges over the Constituent Assembly and waited for a chance to strike back.

Thus the Allies saw the Soviets as an enemy, and possessed the assets on the ground to wage a struggle against them.

The original purpose of intervention was to rebuild a front against the Germans in Russia, either with the Reds or over their dead bodies.

It is often denied that the Allies wanted, at this stage, to overthrow the Reds. But this second aim of intervention, the overthrow of the Soviet regime, was neatly encapsulated in the first aim from the very beginning.

If the destruction of the Soviet power was only of secondary concern at this point, that is only because the Allies had contempt for that regime. They believed that the Tooting Popular Front had seized power by accident in a temporary episode. They believed the Soviet regime would collapse sooner or later, with or without their intervention.

The first aim was foremost while the war continued; the second aim became obvious when intervention not only continued but deepened after the war’s end.

But counter-revolution would not have assumed the explosive form it did without the Czech Legion. The time has come to explain what this force was doing in Russia.

CZECH LEGION

On Russian soil in 1918 there were tens of thousands of Czech and Slovakian soldiers. Czechia and Slovakia were oppressed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire. A Czechoslovak Legion was initially recruited from among immigrants in Russia, then from among prisoners of war. They were induced to fight with the promise of an independent state after the war. By 1917 the Czechs made up a whole Corps, numbering 30,000-70,000 and fighting on the Eastern Front against the Germans and Austrians, under Russian officers and with liaisons and attachés from the Allied powers.

A Czechoslovak scout

The Czechs[vi] did not join in the Russian Revolution. While the Russian army disintegrated, the Czechoslovak Legion remained cohesive. The Russian soldier deserted and went home to his land. The Czech had no home. He was fighting against Germany and Austria to secure one, and he was determined to carry on the fight.

Virtually all other military forces, both White and Red, were either in the final stages of collapse or just coming into being. In the Legion, then, the Allies possessed a unique asset that could really test the strength of Soviet power: a military force that was large, cohesive and present.

Various telegrams and other communications between British agents on the ground and their superiors in London are referred to in the postscript which Peter Sedgwick has added to Victor Serge’s book Year One of the Russian Revolution, published by Haymarket Books, 2015. Taken together they show the outlines of the Allied plans, which had four main elements:

- A revolt of the Czech Legion against Soviet power, possibly linking up with the White warlord Semyonov, who was raiding across the border from China.[v]

- Several central Russian towns to be seized by officers, Black Hundreds, Right SRs etc, designed to encircle Moscow.

- These Czechs and White Guards to link up with the British, French and US forces at Archangel’sk, in the far north of Russia.

- Another element of the plan was outlined by Balfour, previously a critic of intervention: the Czechs could be used to trigger a conflict, drawing in Japan and the US who had been reluctant up to that point. ‘If we act, the Japanese will; if the Japanese do, the United States will.’[vi]

General Lavergne of the French mission in Russia, after explaining this plan to a colleague, added, ‘But I shall feel guilty because, if our plan succeeds, the famine in Russia will be terrible.’ The plan did not succeed entirely, but as we will see the resulting famine was indeed terrible, probably beyond Lavergne’s ability to comprehend.

The French had a second misgiving about the plan: they would rather have the Czechs on the Western Front. But these were misgivings, reservations, not opposition. Simply put, Allied agents ‘had been plotting for [a Czechoslovak revolt] since… late 1917.’[vii]

The Czechs themselves, for the most part, wanted to get out of Russia and to fight on the Western Front. Both the Tsar and Kerensky had refused to let them go. The Reds, however, made a sincere effort to grant this wish. At first there was no ill-feeling between the Reds and the Czechs; the Czech rank-and-file were mostly republican or social-democratic in their sympathies. Czech leader Masaryk had ignored appeals from Alexeev to join the White Guards. The Reds allowed them to travel with 168 rifles and one machine-gun per carriage – this shows trust, not draconian suspicion (and on top of this, the Czechs had concealed weapons).

But the Soviets were bedevilled by the challenges of transporting tens of thousands of soldiers out of a vast, hungry, war-torn territory. First it was decided – by the Reds and the Allies – that the Czechs were to circumnavigate the globe via North America to get from the Eastern Front to the Western Front. So the Soviets began to move the Czechs from European Russia to the Pacific Ocean. But on April 4th Japan (a member of the Allies) made a first tentative landing at Vladivostok in the far east, which was the Czechs’ destination. Later in the year the Japanese would occupy eastern Siberia with an army of tens of thousands, so Moscow’s fear that the landing was part of a full-scale invasion was reasonable. This fear meant that the Czechs were left stranded for a week, strung out in detachments all along the Trans-Siberian Railway from the Volga to Vladivostok. Tension was rising: on April 14th a Czech congress demanded more weapons, plus control over their locomotives.

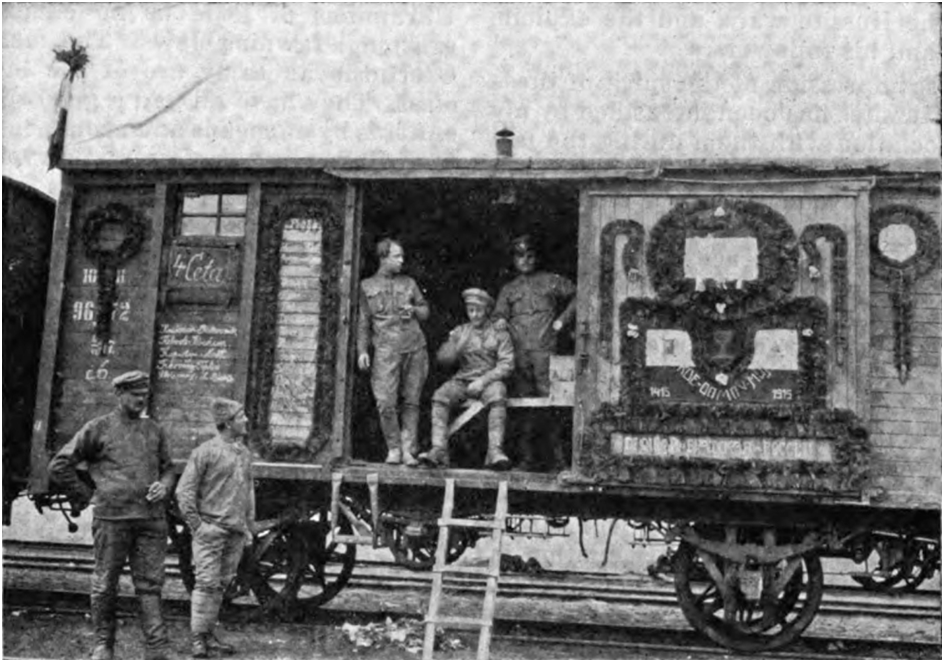

Czechs on the railways

Meanwhile it was far from pleasant for the Czechs to be high and dry at railway stations spread across the whole breadth of revolutionary Russia. Raids by White warlords caused further delays, and these delays bred distrust. Local soviets were sometimes truculent, even hostile. The Czechs, egged on by SRs and Allied agents, suspected that the Soviets were working hand-in-hand with the Germans and were somehow plotting to hand them over. The Soviets, on their side, suspected that the Czechs might join the White-Allied cause.

Czech fears were delusional in that there were no German soldiers within thousands of kilometres of even the westernmost of the Czech detachments. But millions of people were moving across Russia at that moment in the opposite direction to the Czechs, prisoners of war from the German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish empires, released and being borne home (Among them was Josip Broz who would later be known as Tito, Bela Kun who would lead the Hungarian Soviet Republic, and the writer Jaroslav Hašek). The Czechs identified these former POWs as proxy Germans, as a threat. Even if they weren’t a threat, they were still a nuisance to the Czechs, burdening the railway system and causing further delays. The tragedy is that they were mostly subject peoples of Austria, like the Czechs, and like the Czechs all they wanted to do was go home – and, no doubt, like the Czechs they were frustrated with the state of the railways and the often-squalid and chaotic conditions in Russia.

In short, there was a massive armed-to-the-teeth traffic jam on the railways, and no solution in sight. An alternative plan to move half of the Czechs north and ship them out of Archangel’sk was agreed by the Allies and the Soviets. But the Czechs were angered by this plan, and further frustrated by another week-long delay caused by White attacks.

On May 14th, Czechs going east and Hungarians going west met at a railway station in the Ural town of Chelyabinsk. In that same town at that moment a Czech congress was taking place, discussing how to get out of Russia.

At first the Czechs and Hungarians were friendly enough; the Czechs shared rations. Then an argument broke out, and a Hungarian threw a scrap of iron at a group of Czechs. Someone fell – scholars are not sure if it was a fatality or an injury. Czechs lynched the Hungarian.

The Chelyabinsk town soviet investigated the murder and arrested several Czechs for questioning. The Czechs were furious. They sent two battalions into town, disarmed the Red Guards, seized the arsenal and freed their comrades.

The situation in Chelyabinsk was actually settled by negotiations. But by then word of it had got out, and there was no going back. ‘To the Bolsheviks,’ says Silverlight, ‘the Chelyabinsk incident must have looked like unprovoked aggression.’ Trotsky, the Commissar for War, ordered the arrest and disarming of the entire Czechoslovak Corps.

I’ve mentioned that there was a conference going on in Chelyabinsk during all this drama. Allied agents met with the leaders of the Czech Legion at this conference and on May 23rd the Czechs agreed to join an all-out armed struggle against the Soviets. Two days later, on May 25th, Trotsky ordered that the Czechs not just be disarmed, but that any armed Czechs be shot on the spot.

In some accounts I’ve read, all the above is summarised very quickly, and the impression is given that Trotsky’s second, more severe order to disarm the Czechs was the inciting incident.

While Trotsky issued his orders, violence was flaring up in half a dozen places along the Trans-Siberian Railway. In town after town, the Czechs drove out Soviet power. There were 15,000 Czechs in Vladivostok – who were still there because the Allies had, through negligence or design, failed to provide ships to get them out. On June 25th these Czechs seized the town and linked up with the Allied naval forces which had been gradually massing in the harbour all year. By this stage they were fully committed to all-out war.

Silverlight attributes this all to a string of misunderstandings. This is a common trope. I am less charitable. It seems clear to me, beneath the usual plausible deniability, that the British and French governments each played a role in using the Czechs to trigger a war. French policy was more reluctant (they wanted the Czechs on French soil to defend Paris, on which the Germans were advancing) but they were also more active in funding Russian counter-revolutionary groups. It’s difficult to see how things could have gone down the way they did without the Allies’ utterly deluded project of rebuilding a front against Germany.

The Czechs’ perspective seems to have been that the Bolshevik adventure would collapse and a new Eastern Front for World War One would take shape in Russia. What they ended up doing was setting up a new Eastern Front within the Russian Civil War. Their tragedy is that all they wanted to do was get the hell out, but in their impatience they triggered a war from which they would struggle to extricate themselves for two more years.

The plans of Britain and France were partly frustrated. Their forces in the Arctic would have been too little, too late to help the Czechs or the Whites. That would be if the Czechs had consented to march north, which they did not. The plan for White-Guard risings fell short by a long way, as we will see in the next post. In short, the French and British conspiracy came off about as well as any plan of such ambition and scale could be expected to, in the confusion and vast distances of revolutionary Russia. Also, they spectacularly underestimated the stability and social base of the Soviet regime.

But that last point was not at all obvious in the Spring and Summer of 1918. The result of all these plans was an earthquake under the feet of Soviet power. The Czech Revolt presented an opportunity for all the organisations of counter-revolutionaries and many of the Cossack hosts to rise up. ‘Revolt flared along the powder trail of the [Czech Legion’s] scattered elements, stretching over 4900 miles of the Trans-Siberian Railway.’[viii]Moscow was cut off from a vast and rich territory, from tens of millions of workers and peasants.

Another detail from Map 3 of the series. Moscow and Soviet territory are in the north-west corner. Note what a vast expanse of territory they don’t hold. The Green men represent Allied-oriented soldiers – Czechoslovaks, for the most part, stretched out across the Trans-Siberian from The Middle Volga all the way to Lake Baikal. The French flag represents the French officers who staffed the Legion – they were formally part of the French Army. The yellow flag surrounded by outward-thrusting yellow arrows is marked ‘Komuch’. The sinuous red arrow may represent the workers of Ekaterinburg, Troitsk and Verkhne-Uralsk in their heroic march under Blyukher (I’m not sure if the geography is right so it might represent something else). The execution of the royal family is marked by an X over the crown. See the green-and-white Siberian flag raised at Omsk. All the yellow pockets represent the Right SRs – the ones in the far east are marked “SR detachment” and “People’s Army.”

KOMUCH

Under the wing of the Czechs, new White governments sprouted like mushrooms after rain. They expanded, shrank, absorbed one another peacefully or at gunpoint.

The most interesting of the new governments was led by the Right SRs. In early June Czechs were passing through Samara on the Volga on their way east. Local Right SR party members convinced the Czechs to stay and to help them seize power. The Czechs agreed. On June 9th at dawn they overthrew Soviet power in Samara. That evening the Committee of Members of the Constituent Assembly was set up. The name, abbreviated as Komuch, claimed the dubious electoral mandate which we looked at in Part 3.

Komuch was later referred to by Soviet historians as part of the Democratic Counter-Revolution. It is tempting to put scare quotes around the word ‘Democratic’ there; in the formal sense of being elected, the rule of law, democratic freedoms, etc, Komuch was no more ‘democratic’ than any other force operating in the war-torn Russia of 1918. The Constituent Assembly was in its name, but it never got a quorum of deputies together in one place. According to a report from a Komuch organ, ‘At Simbirsk, most of the Red Army soldiers captured in the town were shot. There was a real epidemic of lynchings.’ In August Komuch set up its own repressive police organ to parallel Moscow’s Cheka.

But the term ‘Democratic Counter-Revolution’ does not refer to democratic forms. It refers to property. Komuch was bourgeois-democratic in the classical sense that it was anti-landlord but pro-capitalist. It did not attempt to give the landlords back their land, but it ended workers’ power in the factories and brought back the private owners.

Cathedral in Samara, some time around 1918

FAILURES OF THE RED ARMY

How was the new Red Army coping with all this?

When the Czechoslovak Legion revolted in the east, the Red Army was a thousand-plus miles away and facing in the other direction. As Mawdsley says, ‘the new army was pointed backwards.’[ix] Along with the simultaneous Cossack Revolt in the South, the Czech Revolt marked the real start of the Civil War. It should be obvious how little the Red side expected or prepared for, much less planned or wanted, that war. The Red Army had designated the Volga and the Urals as ‘Internal’ not ‘Border’ regions. So little did the Soviet government anticipate civil war in the east that their contingency plan in the event of German invasion, as we have mentioned, was to retreat east and form an ‘Uralo-Kuznets Republic’ in the Urals and Siberia. That was obviously off the agenda now.

Meanwhile in the Urals and along the middle third of the great arc of the Volga, local Soviets surrendered or fled without a fight. Where the Red Guards tried to fight back, they suffered humiliating defeats. Trotsky held out hope, manifested in alternating dire threats and magnanimous appeals, carrots and sticks, right up until November, that the Czechs could be split along class lines like the Don Cossacks in January 1918. It was not to be.

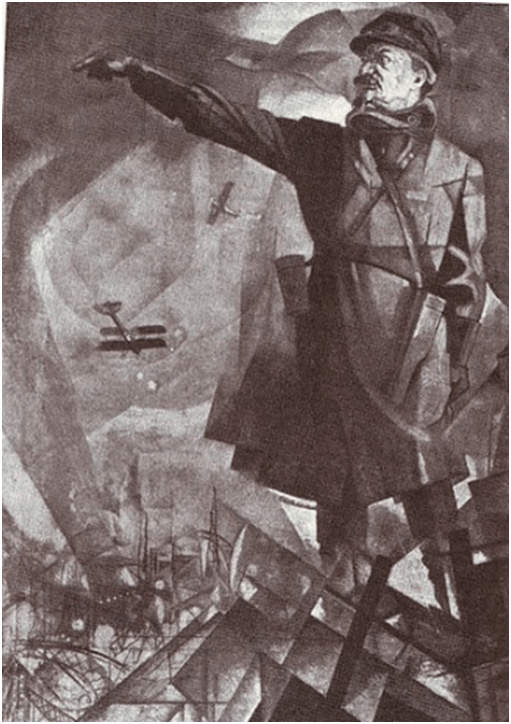

Trotsky, Commissar for Military and Naval Affairs

Irregular ‘detachments’ of workers, thrown together from whatever volunteers presented themselves, had been sufficient in the early months after the October Revolution. But now full-scale civil war had broken out. To win, the Reds needed a real army. This was something they did not have. Facing the Czechs near Chelyabinsk, for example, was a force of 1,000 armed Red Guards, made up of thirteen local detachments numbering from nine members to 570, each with its own commander, each pretending it was autonomous.

By the river Kyshtyma, Red Guards heard a rumour that the enemy were approaching their home villages; whole units deserted the frontline to defend their own homes.

Nearby, the Seventh Ural Regiment was absent from its positions. The commander reported: ‘The men wanted to get themselves dry and have a sleep; they decided to go off only for half an hour but are still sleeping; I can’t do any more.’[x]

KOMUCH IN POWER

Faced with this kind of feeble resistance, or even sometimes no resistance at all, the Czechs took over the Middle Volga region. Komuch would set up shop in each locality before the dust had settled. French officers would start to appear in great numbers. Students and Russian officers would go on a reign of terror against local workers, and Komuch would make half-hearted and impotent appeals for the killing to stop.

According to the Czechoslovak nationalist leader Beneš, ‘The Czechoslovak army on principle shoot every Czech found fighting with the Red Guards and captured by them, for instance at Penza, Samara, Omsk etc (200 at Samara).’[xi]

Czech Legion members, later in 1918

Komuch would restore the bosses to their factories and end fixed grain prices. On the other hand it would confirm the peasants in the ownership of the land. It flew red flags over public buildings and held peasants’ conferences. It formed a military force called the People’s Army. It even attempted to set up a Soviet – which was hastily disbanded after it passed a Bolshevik resolution!

At its height, this state had twelve million people in its territory. It held rich land, key transport links and important cities such as the capital, Samara. It included at its furthest reaches the factory town of Izhevsk. The munitions workers there, who were loyal to the Right SRs, rose on their own initiative to join Komuch – a unique episode of an armed workers’ revolt against rather than for the Soviets. ‘The Samara Komuch never paid much attention to distant Izhevsk.’[xii] But the Izhevsk workers formed a cohesive unit in successive White armies.[xiii]

Mawdsley asks, ‘Did the [Izhevsk] rising foreshadow what would have happened had the People’s Army succeeded in striking west?’ There are good reasons to doubt it. It is striking that in a territory embracing 12 million people, there was only one Izhevsk.

The wealthy classes owed a lot to Komuch, but they did not repay it with loyalty. The well-off citizens were happy to carry out terror in the rear, but in general did not deign to go anywhere near the frontline. One business owner summed up the attitude of the wealthy to the struggle between Komuch and the Reds: ‘When two dogs are fighting, a third shouldn’t join in.’ In the eyes of the bourgeoisie, the Right SRswere on the same canine level as the Bolsheviks.

Recall Lenin’s anxious remark as he contemplated the Komuch territory on a map: ‘I know the Volga countryside well. There are some tough kulaks there.’ He was born and raised in Simbirsk, which fell to Komuch on July 22nd. We can safely assume that the Middle Volga kulaks (the relatively rich peasants) were happy to be out of the grip of Soviet power; now they could sell their grain at whatever price they liked, or indeed not sell it at all. But the poor and middle peasants showed no enthusiasm for the new regime. The Right SRs had received a very impressive vote in this region in the Constituent Assembly elections, but in the end that didn’t translate to very much.

Komuch attempted to recruit 50,000 soldiers from the rural population, but only managed 10,000-15,000. After this failure 30,000 were conscripted. There was no time to train them up, and arms were in short supply, so a large part of the People’s Army was shut up in barracks. There were small, capable detachments under a talented and popular commander, a Russian officer of the Czech Legion named VO Kappel. With considerable Czech assistance, these detachments took town after town. But they were always on an exhausting itinerary, being shuttled up and down the Volga fighting the Reds in one place after another.

In general, as we have seen, workers were hostile to Komuch. For every Izhevsk, there were several stories of heroism on the part of Red-aligned workers. The people of Ekaterinburg, Verkhne-Uralsk and Troitsk, miners and factory workers, formed a partisan army to oppose the Czechs. This army consisted of 10,000 fighters, followed by civilians in carts with their samovars and household linen. Surrounded, they had to fight their way over mountain ridges and across rivers, covering 1,000 miles in fifty days. Arms were scarce; many fought with pikes and clubs and even old weapons from museums. They manufactured their own bullets wherever they could find equipment. At around the same time, a similar Anabasis was taking place in the South, where the Taman Red Army escaped from the Kuban Cossacks.

Vasily Blyukher, leader of the 10,000-strong partisan army of Ekaterinburg, Troitsk and Verkhne-Uralsk

Heroism by itself was not sufficient to win this war. But it mattered. When Service writes that the October Revolution was basically a matter of Trotsky firing up a bunch of ‘disgruntled’ soldiers, and when Ulam claims that the Bolsheviks deliberately fomented chaos in order to step into a power vacuum, and when a documentary on the Russian Revolution gives no reason for its success except ‘the skilful use of black propaganda,’[xiv] they are wide of the mark. The revolution was not some trick played behind the backs of the people. It would not have survived without the sincere enthusiasm of millions. The heroic marches in the Urals and the Kuban were of minor military significance in themselves. But they were evidence of that enthusiasm and spirit of self-sacrifice, which would prove decisive over the next few years.

SAMARA AND OMSK

While Komuch fought with the Reds to the west, it was waging a peaceful but bitter struggle with a rival White government that had sprung up to its east: the Provisional Siberian Government.

The vast expanse of Siberia was populated by Russian settlers and a wide range of indigenous peoples. Class distinctions were not so stark here as elsewhere, and the Communist Party had received only 10% of the Constituent Assembly votes – as against 25% nationally. Three-quarters of Siberian votes had gone to the SRs. Since then, ‘hamfisted’ attacks on the farmers’ co-operatives had damaged the popularity of the Soviets. There were solid Red Guard units in Siberia – but they were away beyond Lake Baikal far to the east, battling the warlords Semyonov and Ungern. Meanwhile there were several Cossack hosts ready to kick off rebellion at any moment – the Siberian Host alone numbered 170,000 – and an underground White network of 8,000 officers, one-third of them concentrated in the city of Omsk.

When the Czech revolt took place, all this dry kindling went up in flames. The Cossacks and the officers rose up. Here as on the Volga, Czech assistance was key; there was only one city (Tomsk) which the Siberian Whites captured without their assistance. But Soviet power was wiped off the map of Siberia. Workers took to the forests and formed the nuclei that would later become Red partisan armies.

From the chaos emerged a new power, centred on the city of Omsk: the Provisional Siberian Government, founded at the end of May.[xv] This government flew a white-and-green Siberian flag – white for snow and green for the coniferous trees of the taiga. This was a nod to a tradition of Siberian regionalism, which The Provisional Siberian Government (henceforth ‘Omsk’ for short) managed to bring on board, albeit in a way that was only ‘skin-deep.’[xvi] It was a stern conservative regime which represented the rifles and sabres of Tsarist military remnants rather than any popular mandate, even a contrived one.

The Iron Bridge, Omsk

In Siberia the SRs were even more popular than on the Volga. But in Siberia, even more so than on the Volga, this support base punched below its weight. This proved how passive and confused that vote was. There was an elected Siberian Regional Duma, which Komuch and the SRs attempted to convene, but the Omsk Government shut it down. This was one of many significant clashes between Komuch and Omsk.

Komuch was not the only example of the Democratic Counter-Revolution. At this point it’s worth getting ahead of ourselves chronologically to look at the trajectory of some of the other governments in a similar mould to Komuch. The British in Persia linked up after the fact with an uprising in the Transcaspian region on 11-12 July. The Reds were chased out, and a Transcaspian Provisional Government led by SRs and Mensheviks ruled there until January when it was replaced by the ‘far more conservative’ Committee of Social Salvation. In July 1919 this government merged with the White regime of General Denikin in the south of Russia. In short, this Central Asian equivalent of Komuch was cannibalised by the reactionary generals.

The snows of North Russia saw the same political developments as the sands of Central Asia, only at a faster pace. On August 2nd the British forces landed at Archangel’sk. On the same day, the Archangel’sk Soviet was overthrown in a military coup, and the Supreme Administration of North Russia came to power. This was staffed by Right SRs and led by Chaikovskii of the Popular Socialist party. On September 6th the local military forces, supported by the Allies, overthrew this ‘moderate socialist’ government. Chaikovskii was first deposed, then brought tentatively back into the fold, then exiled.

Smele writes:

On the day of Chaikovskii’s departure, 1 January 1919, there duly arrived at Archangel’sk General EK Miller, who was to become military governor of the region for the remainder of the Civil War in the North. They must have passed each other in the harbour; socialist democracy was leaving Russia as White militarism disembarked.[xvii]

The ‘Democratic Counter-Revolution’ had suffered the same fate in Central Asia and in the Arctic Circle: a government of ‘moderate socialists’ had come to power with the help of right-wing authoritarian officers and Allied interventionists, only to realise sooner or later that it existed on their sufferance, that it had no social base of its own, that in the polarised conditions of civil war the fate of ‘moderates’ could not be a happy one.

Would things turn out the same way for Komuch?

Later we will trace a similar conflict between ‘moderate socialists’ and militarism in the relationship between Komuch and Omsk. But at the height of the revolt in Siberia, in July, seismic events occurred behind Red lines, and these will be the focus of the next post.

Sorry the footnotes are a mess. I’ll sort them out when I get a chance. Though they are in two different formats, it should still be possible to follow up any quotes or facts.

[i] Robert Silverlight, The Victors’ Dilemma: Allied Intervention in the Russian Civil War, p 8-9

[ii]Silverlight, 10

[iii]Silverlight, 19

[iv]Silverlight, p 33

[v]Silverlight, p 35

[vi]Silverlight, p 36

[i] Tsederbaum (not Zederblaum) was actually the name of Lenin’s former comrade, now opponent, Julius Martov of the Menshevik-Internationalist faction.

[ii] Ransome, Arthur. The Truth About Russia. 1918. https://www.marxists.org/history/archive/ransome/1918/truth-russia.htm

[iii] Bryant, Louise, Six Red Months…, Chapter XXXI. https://www.marxists.org/archive/bryant/works/russia/ch31.htm

[iv] Taylor, AJP. The First World War…, p 205

[v] Dr Zhivago imagines that, at the fictional battle of Yuriatin, the Red and White commanders are former neighbours and revolutionary comrades from Moscow. While I have questions about the novel’s timeline, I think this detail is plausible enough.

[vi] It is fair to refer to them as Czechs since only around one in ten were Slovaks.

[vii] Smele, The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, 68

[viii] Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War, 64

[ix] Mawdsley, 82

[x] Serge, Year One, 311

[xi] Serge, 496

[xii] Mawdsley, 90

[xiii] Khvostov, The Russian Civil War – The White Guards, p 46. They addressed one another as ‘comrade’ and attacked to the music of accordions. They maintained their cohesion right to the end of 1920, after which many settled on farms in Manchuria.

[xiv] See (or don’t!) Service, Robert, Trotsky: A Biography, Belknap Press, 2009, Ulam, Adam B, Lenin and the Bolsheviks, 1965, The Russian Revolution (documentary film), Dir. Cal Seville, 2017

[xv] For the first month of its life it bore the name ‘Western Siberian Commissariat’

[xvi] Smele, 70

[xvii] Smele, 72