The point that this book has been hammering home is that hunter-gatherers were not ‘innocent’ or just roaming bands. Not only did foragers of the Stone Age have complex social structures and build great monuments, they were politically self-conscious and sophisticated.

Building on this, Chapter 5, ‘Many Seasons Ago,’ describes two very different cultures which lived along the Pacific coast of North America, drawing a series of fascinating comparisons and contrasts between the two. But the arguments and conclusions, this time, I found far less convincing than in previous chapters.

The argument is in essence: look at how radically different these two societies were, even though they had the same mode of production. So, isn’t the idea of a mode of production a bit useless?

The two North American ‘culture regions’ Graeber & Wengrow outline are the Californian Region and the North-West Coast Region. These were not pre-agricultural societies, the authors argue, but anti-agricultural – ie, they knew about farming but chose not to practise it.

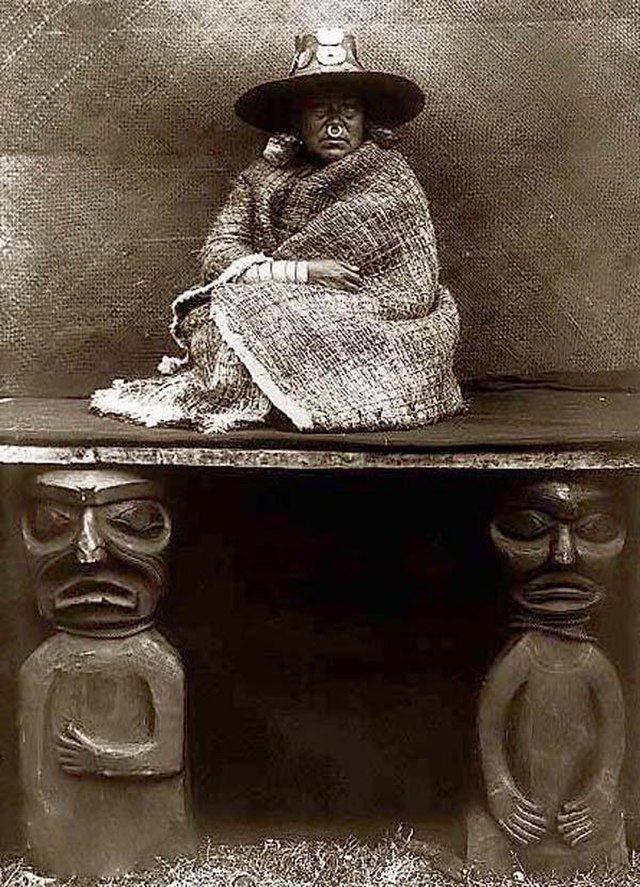

Within this, as the most striking examples of the two regional cultures, they zoom in particularly on the Yurok (California) and the Kwakiutl (North-West).

Let’s try to sum up what Graeber and Wengrow put forward here.

- They say that idea of a ‘culture region’ is not perfect but makes more sense than ranking and sorting societies based on ‘mode of production.’ In other words, let’s group different societies based on what games, foods, clothing and values they share, not on whether they are foragers, farmers or industrial workers.

- They say that societies (or at least these societies) are ‘ultimately’ shaped by political and cultural dynamics, by human agency, and not by ecology or economics. Concretely, the Kwakiutl ate salmon and the Yurok ate nuts and acorns, but that had nothing to do with their respective social structures.

- Societies define themselves against their neighbours – ‘dynamically interconnected [and] reciprocally constituted’ (Marshall Sahlins.) People traveled a lot in the Stone Age and were aware of neighbours’ customs and tech. What they consciously chose not to borrow is what defines each group: we are the people who don’t go in for slavery, who prefer a spartan aesthetic, etc.

So what do I think of all that?

I come to this without much prior knowledge, but it seems to me that the Yurok and Kwakiutl are bad examples for what the authors are trying to argue. Their means of subsistence could be crudely grouped together as ‘forager’ but were radically different. Culture and politics are weird and wonderful, so I’d agree that you can’t say that X climatic-economic input produces Y political-cultural result; if I say that the Kwakiutl eat fish, therefore they make colourful masks and enslave people, clearly there’s a missing link in the argument. But even though we can’t trace the causal relationship, I intuit strongly that there is one. It’s no coincidence that the people who lived on a diet of fatty, oily creatures made a virtue of amassing fat in their possession and in their own bodies. The people who hunted fish also hunted people. The people who ate dry, hard, austere nuts preferred not to hunt people, and themselves valued austere simplicity, hard work and physical thinness.

Between input X (the means of subsistence) and its many, practically untraceable outputs there is plenty of room for randomness and invention, and for the unique historical experiences of a given community, to interfere. It’s delightfully complicated.

Graeber and Wengrow’s thesis is appealing because it assigns the lion’s share of explanatory power to the political initiative of the people themselves. And it’s probably true that western Eurocentric writers are too keen to talk about their own history as a matter of political decisions, leadership, values and principles, while jumping to the most smug, glib, reductive, deterministic explanation they can think of when it comes to someone else’s history.

An idealistic, voluntarist philosophy lends itself well to judging certain communities for conditions forced upon them. But if we make our own choices, we make them from the set of choices available to us. Some people have more and better choices than others. This obvious enough to the authors that at one point they attempt to say, in essence, ‘No, not like that.’ Also, the limits of a given mode of production intrude when the authors acknowledge in passing that the population sizes in these communities were tiny. Neither fish nor nuts could support as large a population as settled agriculture. It’s fair to talk about ‘advance’ or ‘progress’ in relation to productivity of labour.

So they haven’t convinced me that there is a serious ‘problem with modes of production.’ But in the course of their argument they talk about a whole lot of great and interesting stuff. Once again, the journey is such a pleasure that you don’t mind if you never reached the promised destination.