This is part 4 of my on-the-spot reactions to The Dawn of Everything by David Graber and David Wengrow. Here are the first three parts:

Stoned in the Stone Age

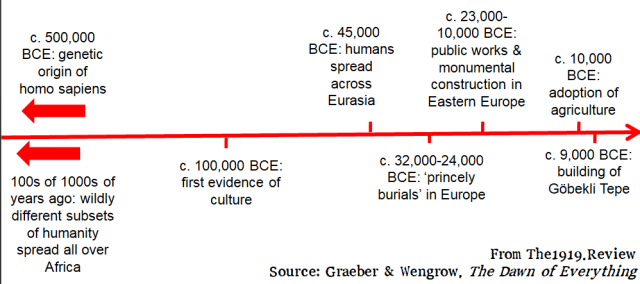

If there’s one thing to take away from this book, it’s that the Stone Age was way richer and more interesting than most of us would have thought. Moving from the Paleolithic (Old Stone Age) to the Mesolithic (Middle Stone Age, from about 12,000 BCE), us humans have not started working metal and a lot of us aren’t farming yet. Nonetheless even those who have not settled down to agriculture are still very busy:

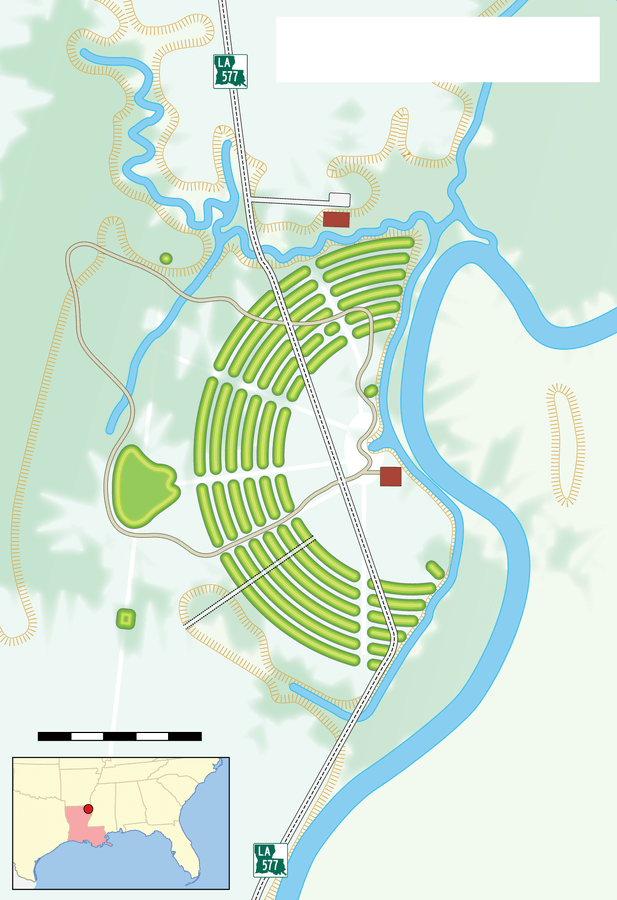

- At Poverty Point, Louisiana, US, there are massive earthworks dating from 1200BCE and larger than the contemporary cities of Eurasia. Analysis of artefacts and of the apparent systems of measurement used by the builders links this site all the way up the Mississippi and to the Great Lakes, and down to the Gulf of Mexico and even Peru. The builders were hunters, fishers and foragers.

- In Japan, we have a wealth of archaeological data showing a rich and complex social life passing through cycles of nucleated settlement and dispersal from 14,000-300 BCE. My notes get a bit scattershot here: OK, they had acorn-based economies, they stored a surplus, they smoked weed, and they left no evidence of aristocracy or a ruling elite.

- In Finland around 2,000-3,000 BCE we have ‘Giant’s Churches,’ massive structures built by the collective labour of hunter-gatherers.

This makes intuitive sense to me. We have seen that hunter-gatherer life could involve seasonal or local superabundance. This allowed for specialisation (people to do the maths and the crafts, the planning, overseeing and mobilising) and collective projects, such as monument building. But since the superabundance was temporary, local or conditional, so was the specialisation, and so was the mobilisation of the people in collective goals. That’s why kings, hierarchies, inequalities tended not to arise. The way I’d see it, agriculture, on the other hand, creates the basis for a permanent surplus, and so a lot more societies start to turn hierarchical, and these hierarchies grow more permanent.

As with previous chapters, we then turn to anthropology, that is, to modern and early modern hunter-gatherers, and see a few examples of where they have had kings (returning to Louisiana and Florida). ‘The economic base of at least some foraging societies,’ the authors conclude, could sustain priests, royal courts and standing armies.

Swallows and summers

The authors make repeated claims that they are overturning conventional wisdom and rewriting history. In this chapter they are arguing that there is no causal link between the widespread adoption of agriculture and the widespread turn to hierarchy, inequality and subjugation, or if there is a link it’s too broad to have any meaning. The evidence they present in this chapter consists of the amazing social and physical structures that hunter-gatherers built – all without agriculture. But are ‘at least some foraging societies’ enough to prove such a big argument? I am very impressed, but not yet convinced. If the stale old ‘conventional wisdom’ still seems to hold for all but ‘at least some,’ then it holds. A dam designed to let through a trickle of water still holds back a massive volume in the reservoir.

Usually the tone is good-humoured, but sometimes it’s nearly a Hancocky tone of denouncing ‘traditional’ and ‘conventional’ scholars. The thing is, it’s not clear to me that this book contains a conceptual revolution, as opposed to merely synthesising, collating, bringing into relief, making informed and imaginative suggestions. So far, more the latter. The authors make bold claims and hedge them, or fail to carry through fully with the evidence. For example they scold us for assuming that pre-agricultural societies were all equal, and regularly caricature that position. Saying that pre-agricultural societies were generally more equal is apparently the same as saying they were childlike and innocent, all one identical blob, or animalistic – except when Graeber and Wengrow say it, as when they acknowledge ‘the flexibility and freedom that once characterised our social arrangements.’ (p140)

To be clear, the project of synthesising, bringing into relief, etc. is more than enough of a reason to read this book. I’m really enjoying it. And often its denunciations of ‘conventional wisdom’ are on point, for example when they describe the idea of writing off 7,000 years of American history as ‘the Archaic Period’ as ‘a chronological slap in the face.’ You don’t have to agree with everything these guys say to appreciate and enjoy the close-up tour of the messy interface between social systems in our deep past.

A reference to Marx surprised me. I assumed that the authors were squishing Marxism and its theory of primitive communism into their general critique of the Rousseau ideological tradition, and I criticised them for not mentioning it. But here they describe primitive communism as the collective ownership and control of the surplus, clearly distinguishing it from more romantic or pessimistic views where communism is only possible with no surplus at all.

‘Conventional Wisdom’

But I’m not done with ‘conventional wisdom’ yet. A lot of the things that are set up and scoffed at as ‘conventional wisdom’ are not really that. Here are a few of them as laid out on page 127:

- ‘…Rousseau’s argument that it was only the invention of agriculture that introduced genuine inequality…’

- ‘It’s also assumed that without productive assets […] and stockpiled surpluses […] made possible by farming, there was no real material basis for anyone to lord it over anyone else.’

- ‘Once a surplus arises, craft specialists, priests and warriors will arise to lay claim to it.’

Reading the above, you’d expect the authors to set about disproving these claims. They do nothing of the kind, at least in this chapter. As we’ve seen, they demonstrate that there are ‘at least some’ examples to the contrary. The built environment from the pre-agricultural age is impressive in absolute terms. As the reader, I have no way of judging whether this is a trickle or a torrent. OK, it’s useful to note that Poverty Point (more pictures below) has a bigger footprint than Uruk – but do all the sites built by foragers in that period have a bigger footprint than all the sites built by farmers?

‘The idea of ranking human societies according to their means of subsistence’ is described as a bad and weird idea that some eighteenth-century freaks thought up and that we have all accepted without question until now. I don’t believe in ‘ranking’ different societies, unless in relation to some specific and measurable quality. But I think that the way people put food in their bellies is actually foundational to how they organise their society. Those hunter-gatherers who changed their political structures every year? They did that because there were changes in how they could get food. It’s true that we look at prehistoric societies more than others through the lens of how they filled their bellies. But that’s entirely justified – because we know next-to-nothing about their politics or culture.

What is more, I’ve never had the above ideas presented to me as ‘conventional wisdom.’ Throughout my own formal education I never got an earful about the primacy of economics. At university we looked at Marxism as one topic of a dozen in Critical Theory, and one topic of a dozen in Historiography, plus Bloch and the Annales school. That’s it.

To be fair, I didn’t study Archaeology as such, or Anthropology – maybe it’s different in those fields. But in the broad public understanding of these fields, none of these claims in my experience constitute ‘conventional wisdom.’ On the contrary, the primacy of politics and warfare is asserted throughout popular history. In school, in the media and in popular culture, we compare societies not by their economic base but by their cultural and political ornamentation, through the prism of personalities and events. Economics gets only an indirect look-in, via inventors. Popular discourse evaluates societies according to the most arbitrary criteria (where for example Sparta somehow represents ‘democracy’) or with the aid of idiotic aphorisms like ‘Strong men create good times [etc]’ or even through the mostly-meaningless and deeply problematic lens of race. That’s where we’re at. We’re really not suffering from an excess of economic determinism.

Work and leisure

There’s a lot more in the chapter. There’s the trope about how people in past ages had more free time than modern office or factory workers, which the authors take as read and don’t attempt to prove. As they note, it holds true for the !Kung people, but not for other foraging societies – the ones in what is now Canada appear to have been workaholics. One thing about the !Kung that I would definitely think is universal, though, is that they know about agriculture, could do it if they needed to, but have no pressing incentive to turn to it.

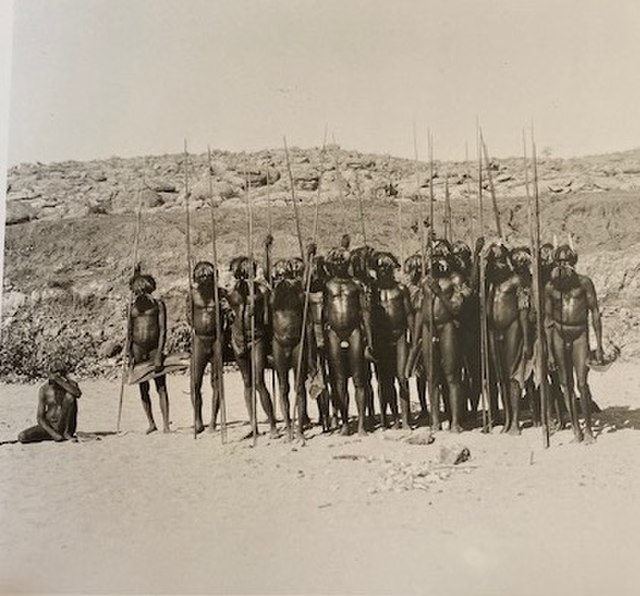

There’s some intriguing stuff about how the only thing close to private property or hierarchy in many forager societies was (is?) the concept of the sacred. The Aranda people in Australia treated their children with kindness but initiation into adulthood involved painful rituals; subjugation and violence was only present in a sacred context. Sites like Poverty Point were probably ‘sacred,’ the only place in the social life of the community where demands for absolute obedience were made.

Linked to this, the authors note about ‘kings’ of the Mesolithic: ‘It is possible for explicit hierarchies to arise, but to nonetheless remain largely theatrical, or to confine themselves to very limited aspects of social life.’ (P 131) This is food for thought for scholars of Gaelic Ireland who are struck by the pedantry of the seating and portioning arrangements which our sources prescribe for a feast. I have a feeling this is building toward a theory of where private property came from, a theory that relegates agriculture to background noise.

But this chapter has not, in my brain anyway, broken the causal link between agriculture and inequality. But the assumption that towns, specialisation, crafts and science are impossible without agriculture is completely wrong. Graeber & Wengrow have proved this hands-down. They have given us a fascinating picture of the real social and political lives of foraging societies and the monuments and social structures they can sustain.

Another powerful point here is that colonisers routinely claim that the land they are seizing is somehow fair game because the people who live there are not working it ‘properly,’ ie they are hunting and gathering rather than farming (And of course, even when they are farming, as in the case of Palestine, the colonisers still have the nerve to pretend they ‘made the desert bloom’). So the idea of foraging as not being a valid economic activity, of not being able to sustain ‘civilisation,’ however you define that, has a blood-soaked and disgusting legacy. This part is conventional (though it was never wisdom) and we can’t dispense with it quickly enough.

Leave your email below to subscribe…

Or…