Revolution Under Siege: Civil War in & Beyond Russia, 1918-1920

In October 1917 the working class of the Russian Empire was the driving force behind the first socialist revolution in history. They overthrew a centuries-old empire in February 1917. After a nine-month interregnum during which a liberal-democratic regime failed to deliver on their most pressing demands, they took power through democratic councils known as Soviets. The new Soviet power hardly had a chance to draw breath, much less to build socialism, before it was plunged into a war of terrible scope and fury. Those who had made the revolution were now drawn in their millions into the armed struggle to defend it. They were the essential core around which the new Red Army was built.

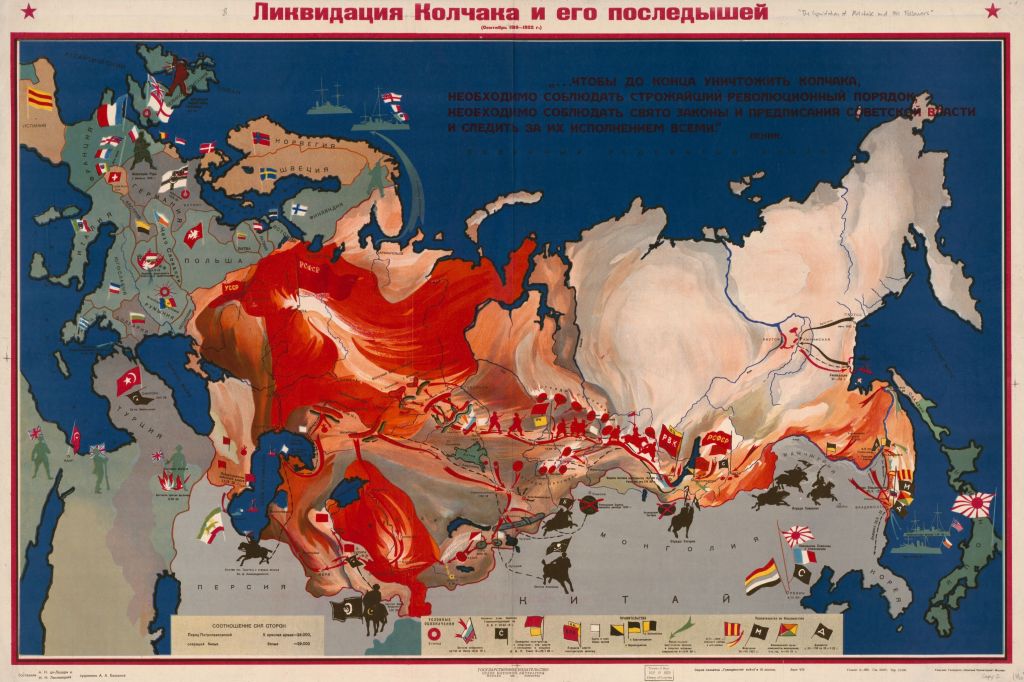

Before the war many workers in the Russian Empire would have worked their ten-hour days with the heat of a blast furnace on their skin. Now they carried its promethean fire to the Arctic Circle and the deserts of Central Asia. They fought from the streets of Moscow to the Siberian taiga and the Mongolian steppe. In the north they were supplied by sleds, in the south by camel caravans. It far from a merely Russian affair – but we call this struggle, for want of a better name, the Russian Civil War.

One relatively small episode in this war was dealt with in The Iron Flood, a 1924 novel by the Soviet writer Alexander Serafimovich. In the summer following the Revolution, the Cossacks rise in revolt against the Soviet power. The flood of the title is a vast mass of men, women and children, supporters of the Soviet regime, whose home villages become enemy territory overnight. They must break out and join up with the Red Army.

South Russia is like a furnace under the summer heat. Behind them, their brothers and sisters are hanging from gallows. Cossacks on horseback pursue them. Some sailors join the column; they are revolutionary but hot-headed. Twice they attempt to lynch the commander of the column. The Iron Flood must keep moving, up mountains and across wastelands. It is bombarded by the guns of several nations, from land and sea. The children die from shrapnel, thirst and hunger. The Iron Flood breaks through an enemy fortress, surviving against terrible odds. But in the moment of victory the author forces us to confront the fact that these enemies were human beings too.[1]

The specific story told in The Iron Flood – the march of the Taman Red Army – is true.[2] More than that, it sums up in an authentic way the chaos, cruelty and heroism of the Civil War. The molten-metal flood of humanity cools, solidifies and triumphs under the column commander, “whose face, jaws, eyes and voice are repeatedly described as being made of iron and steel.”[3] The potent metaphor of flesh turning to metal describes the transformation wrought on the Revolution and the people who made it – for better and for worse – by the furnace of war.

This is Revolution Under Siege, a new series from The 1919 Review that tells the story of the Russian Civil War. The dramatic events of the year 1918 are the focus of Series One, which adds up to ten parts. Series Two will deal with 1919, and a third Series will explore the events of 1920 and later dates. Podcasts based on these posts will go up on Spotify, Youtube, Google Podcasts and other platforms. Soon the existing podcasts will be updated so as to have a human voice.

So you don’t miss any of it, make sure to put your email address in the subscriber box below. Visit us on 1919review.wordpress.com.

*

Under the name “Russian Civil War” we neatly file away a range of conflicts that encompassed one-sixth of the land surface of the earth. Only 44% of the people living in this collapsing empire were Russian in the strict sense. There are over fifteen states in Eastern Europe, in Central Asia and in the Caucusus which include this war as a chapter in their national histories; a Civil War-era flag became a symbol of protest in Belarus in 2020. When, in Series 2, we come to deal with events in Ukraine, the place names will echo the news reports from the current war.This and the involvement of other countries made it “a world war condensed.”[4] Japan, Britain, France, the United States and Germany were some of the countries which invaded Russian lands on every point of the compass. In 1918 the most effective units in the Red and White forces, respectively, were Latvian and Czech. Often, Reds fought directly with Allied soldiers; in 1920, Russian sailors skirmished with the Ghurkhas of the British military on the coast of Iran.

Rather than say that the Russian Revolution spilled over into other countries, it’s more accurate to say that Russia was the most advanced front in a global revolutionary offensive by the labour movement and its allies. Italy had its biennio rosso, “two red years,” Spain its triennioBolshevico, “three Bolshevik years,” Ireland its “Soviet” movement. In Germany and Hungary, there were Soviet Republics in 1919. It’s impossible to draw lines on the map to mark the limits of this war. The title of this series says 1918-1920, but it will be impossible to avoid dealing with events from earlier and later.

In all this complexity there is nonetheless a key and central axis of the war: the struggle between the Red Army and the White Armies. In October, having chosen the Bolshevik Party as their political instrument and flooded into it in their hundreds of thousands, and into the Soviets in their millions, the working class took power. The White Armies came together to destroy this new order. The Red Army was forged in the heat of the struggle to defend it.

This was fundamentally a struggle between classes.

Industrial workers formed the core support base of the Reds. White-collar workers, poor peasants and artisans were drawn to their banner.

On the other side, under the White banner, were big business owners, landlords and the church. The core of the White fighting strength was made up of officers of the old army, cadets and students – the sons of the middle and wealthy classes.

In the Russian empire in 1917 there were 3.6 million factory and mine workers, among 18.5 million wage workers of all kinds. This was a vast and diverse mass of people. But the Russian Empire contained between 150 million and 180 million people. So the working class made up a large minority.[5] The wealthy made up another minority, obviously a much smaller one. Most of the population fell into neither category, but different elements were magnetically attracted to the Red or White poles. Let’s take a brief look at thee of these intermediate social forces: the peasants, the Cossacks and the intelligentsia.

Peasants, those who worked in agriculture, made up two-thirds of the population. 80% of the total population of the Russian Empire lived in the countryside. The peasants were a diverse category – very different income levels, nationalities and social forms existed. Over the course of the war, peasant attitudes toward the Reds embraced two extremes of enthusiasm and hostility, and everything in between. But there was a consistent attitude of sullen hostility to the Whites, the faction of the hated landlords.

The Cossacks were a privileged military caste, several million people settled on the borders of Russia. Without them, the White Armies would simply not have been viable. Only one-fifth of those who fought did so under the Red flag. But from the point of view of the White leaders, they could be unreliable.

The professional middle classes made up another large minority. These were doctors, lawyers, etc, known in Russia as the intelligentsia. They had always seen themselves as the leaders of the revolution. But when the revolution happened, they were afraid of the factory workers and soldiers who had taken control. Some of the intelligentsia were Red, more tended toward the Whites early on; some changed sides as the war went on.

One of the repeating themes in the Civil War is that these intermediate forces again and again attempt to organise some third force, and to break the bipolar struggle of White and Red. All these attempts ended in failure. Early on, they tended to be subsumed into the White camp, later into the Red. The various ‘third forces’ generally ended up acting as transmission belts into Red or White.

There is a reason why some of the most well-known novels to come out of the Civil War focused on the intelligentsia (Doctor Zhivago) and the Cossacks (Quiet Don). These were the social layers caught in the middle of the Civil War, tortured by their split loyalties. However painful such conflict is for human beings, literature thrives on it.

This fact hints at why, in spite of the complexity, most scholars continue to regard this as a single war. It is because a single overriding question was at issue: whether the October Revolution would stand or fall.

*

The Russian Civil War doesn’t look anything like the First or Second World War. We usually don’t get to see clear frontlines, or two sides neatly differentiated by crisp mass-produced uniforms. Usually in popular military history, officers and politicians are making all the decisions –human agency is a monopoly of the top brass. Barring the catastrophic defeat of such-and-such a corps or such-and-such a division, we expect it to remain qualitatively the same from month to month and even from year to year.

In this war, none of this could be taken for granted. A White general wrote of

‘those real moral and material coefficients, which alone determine the combat value of any unit, its stability, reliability and effectiveness. [These coefficients are] determined by the sum of the qualities of superiors and cadres […] and the conditions of service of the unit, its fatigue, lack of supplies, etc., etc. Before the revolution, these coefficients were on average more even and were less subject to various fluctuations; now absolutely – they have gone deep down, and relatively – they have become very diverse and capricious.’

Diary of General Budbreg, June 10th 1919

It was not rare for a regiment to decimate itself overnight in a bloody mutiny, and go over to the other side. The bold coloured arrows on maps were frustrated, on both sides, by train cars falling apart, fuel shortages, mutinies, mass desertion and guerrilla warfare.

We expect revolutionary war to be unconventional. But the Russian Civil War also defies what we expect to see in an unconventional war. Those who have read about the Chinese, Cuban and Vietnamese revolutions are primed to think that revolutionary war is guerrilla war. But long before Mao and Che, it was the White Guards who retreated to remote areas, carried out raids, sent agents into the enemy rear, and perished in terrible numbers on heroic ‘Long Marches.’

So did the Reds, at times, as The Iron Flood will attest. But the Reds won the war by building a regular and professional army, albeit an army of a kind never seen before or since.

This war is unique in history. Unlike in Cuba, China or Vietnam, the revolutionary war in the former Russian Empire was worker-based and not a rural guerrilla struggle. Unlike in Eastern Europe after 1945, it was a mass popular movement and not largely a bureaucratic ‘revolution from above.’ And unlike the Paris Commune or the Spanish Civil War, this working-class, popular revolutionary war was victorious.

*

By the end of summer 1918 it was total war, desperate and cruel. But it was fought in the wake of the First World War, against a backdrop of exhaustion and collapse. In World War One the Tsarist army had placed 300,000 cavalry in the field; by 1920, the Reds were proud to have a First Cavalry Army numbering just 16,000.[6] The Civil War was fought with the improvised human and material leftovers of the World War, and there was something post-apocalyptic in its aspect.

The Russian Revolution was a belated rupture between medieval and modern. This fault line is visible in the striking image of the tachanka, a type of weapon used by the Reds and the Anarchists: a horse-drawn cart with a Maxim machine gun bolted onto it. Reds and Whites alike tallied up their armouries not just in rifles but in swords. Armoured trains with naval guns dominated the railways. In some places, metalworkers forged pikes when no rifles were to hand.[7] Men and women fought for a classless, stateless, high-tech future society, while wearing boots made from the bark of a birch-tree.

A greater number of Russians died in combat in World War One than in the Civil War. But years of Civil War compounded the famine and epidemics that had already come to the boil during the World War. In 1917 factory owners began on a huge scale to close down, lock up or sabotage their premises and equipment; from the end of that year White Armies blocked Russia’s internal supply lines. The harsh winters of 1918, 1919 and 1920 were hell in the cities, and Saint Petersburg was literally half-deserted. Millions perished in rural areas during the famine of 1921-2. This mass mortality consumed the people with every day that the Civil War ground on. By the end, it added up to a yawning demographic gulf. Terror, practised by all the contending forces, made its contribution to the death toll, and it was not a small contribution.

*

On the eve of the October Revolution, writes a worker who would soon be marching in the Red Army, ‘We certainly did not understand the dictatorship of the proletariat as a dictatorship of the Bolshevik party. Quite the contrary. We were looking for allies, for other parties willing to go with us along the path of building soviet power […] NovaiaZhizn’, the newspaper of the Menshevik-Internationalists, enjoyed even greater success at our factory than Pravda. So we were by no means pure sectarians, for whom party truth was higher than the truth of reality.’ [8]

This account will trace how the conflict ground down this democratic attitude. The Civil War created several necessary conditions for the rise of Stalinism – that is, for the establishmentof a dictatorship which, two decades later, claimed the lives of most of the political and military leaders of the Revolution.But for Stalinism to arise, other vital conditions were necessary too. An account of the Civil War which works backwards from Stalinism, or worse, which recognises no essential difference between the Lenin and Stalin eras, will have huge blind spots. Supporters of the Reds were fighting for control of the land they tilled, for their rights as women or members of minority groups, for socialism or for democracy. They accepted the need for emergency wartime measures – which included violence and the curtailing of democratic rights, as in the belligerent countries during the World Wars. But if they had been asked to fight for a repressive one-party state they would not have done so. To portray them as dupes of the Bolsheviks is to do a disservice to them – and to the Bolsheviks.

On the other hand, the promise of a better future helped the workers and poor to endure the horrors of war and hunger in the short term. This was not a false promise. The conquests of World War One were to be Istanbul or parts of Poland. The conquests of the Russian Civil War were:

The promise of a better future helped people to endure the horrors of war and hunger in the short term. And it was not a false promise. The conquests of World War One were to be Istanbul or parts of Poland. The conquests of the Russian Civil War included:the eight-hour working day;free healthcare and social insurance;vastly expanded access to education; housing costs reduced to a pittance; the redistribution of noble and church land in favour of tens of millions of people; the right to divorce, abortion and contraception; the de-criminalisation of homosexuality; and language rights and autonomy for ethnic and national minorities.

It is only possible to dismiss these gains if one first dismisses the interests of working-class people, poor peasants, women and minorities as beneath consideration. Of course, we would be naive to think that no historian has ever implicitly made this dismissal. Hence we have many ‘doom and gloom’ accounts of the Revolution and Civil War which withhold any hint of vindication from the protagonists. Hence, even, accounts which explicitly place the Russian Revolution side-by-side with the Nazi holocaust (See the relevant chapter in Rayfield, Stalin’s Hangmen, Viking, 2004).

The massive hunger and violence were not a necessary sacrifice or a means to an end. There was nothing necessary about it. Violence and suffering accompany all wars and revolutions, but in this case the worst of it could have been averted.The Civil War could have ended in April 1918, or in January 1919, if the Whites and the interventionists had been willing to take that course. On the other side, Soviet leaders admitted to serious mistakes, such as clinging to food policies which, certainly by 1920, were doing more harm than good. Mass mortality was not in any sense necessary. It damaged the Revolution, placed limits on its gains, and, along with other factors, helped lay the foundations for Stalinism with all its calamities and crimes.

*

I see in the Russian Civil War a pressing relevance for the 21st-century.The war in Ukraine is the most obvious example. It is of course a fundamentally different war. It has stable frontlines, and neither Kyiv nor the Kremlin have any interest in the labour movement or social revolution. But the echoes are insistent. Belarussian railway workers delayed and diverted Russian soldiers in the first days of the war. Putin in 2005 spoke at the re-interment of the remains of the White general Denikin, attended by thousands; Putin in 2022 levelled cities in the name of the same ‘Russia, One and Indivisible’ for which Denikin waged war. When the Russian armed forcesfailed in early 2022 despite their numbers and equipment, one is reminded ofBudbergand his ‘coefficients.’Kolchak’s big mobilisation, like Putin’s, failed to translate into reliable units. When mass graves were discovered in liberated areas, the disturbing details seemed straight out of the history books. With Azov and Wagner and Kadyrov, and when the Ukrainian government armed Russian fascists and sent them on a raid into Russia, we saw something like the array of irregular and dangerous forces, generously fed by state sponsors, which sprouted during the Civil War. Like the White Guards, YevgenyPrigozhin had Rostov-on-Don and South Russia as his base; like so many unstable and inscrutable atamans of the Russian Civil War, like Kornilov, Gajda, Muraviev and Hrihoriiv, he blazed a searing trail across the world before burning up rapidly.[9]

But the relevance of the Civil war to our time goes deeper. Twenty-five years ago liberal capitalism seemed like the only show in town. But now with pandemics, polarisation, climate change, economic crises and war, the bourgeois liberal utopia seems a lot further away than it did a quarter-century ago. Revolution, reactionand civil war are realities of our time.

No adult with political opinions can read about the Russian Civil War and remain un-invested and dispassionate. I won’t pretend to be neutral. But my sympathy for the workers and poor does not preclude criticism, or a sincere attempt to understand the other side. You know where I’m coming from, and these events are rich and complex enough that, provided I do them justice, different people will take away different things.

M Lenihan

August 2021

Updated September 2023

The cover image for this post is by A. Kokorin, one of the very fine illustrations from The Iron Flood by Alexander Serafimovich, 1973 edition.

The cover image for the series is a painting by M. Plinzner, “Kosaken auf der Wacht an der Mandschureibahn,” from Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Serafimovich, Aleksander. The Iron Flood, 3rd Edition. Hyperion Press, Westport, Connecticut. 1973 (1924)

[2] Serge, Victor. Year One of the Russian Revolution, 1930 (Haymarket, 2015), p 343

[3] Hellebust, Rolf. “AlekseiGastev and the Metallization of the Revolutionary Body.” Slavic Review, vol. 56, no. 3, 1997, pp. 500–518. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2500927. Accessed 18 June 2021.

[4] Smele, Jonathan. The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars 1916-1926, Hurst & Company, London, 2015

[5] Smith, SA, Russia In Revolution: An Empire in Crisis 1890 to 1928, Oxford University Press, 2017, p 39

[6] Davies, Norman. White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish-Soviet War 1919-1920, Orbis, 1983. P 120

[7] Serge, Year One, p 343

[8] Dune, Eduard, Memoirs of a Red Guard, University of Illinois Press, 1993, eds Koenker, Diane and Smith, SA.,p 56

[9] Prigozhin’s ‘March of Justice’ followed the line of march of General Sidorin and the Don Cossacks in 1919, but further, and got about as close to Moscow as Denikin.