‘…the deeds and misdeed of Communism are compared not with the actual behaviour of the world it sought to challenge (about which the strictest silence reigns), but with liberalism’s declarations of principle…’

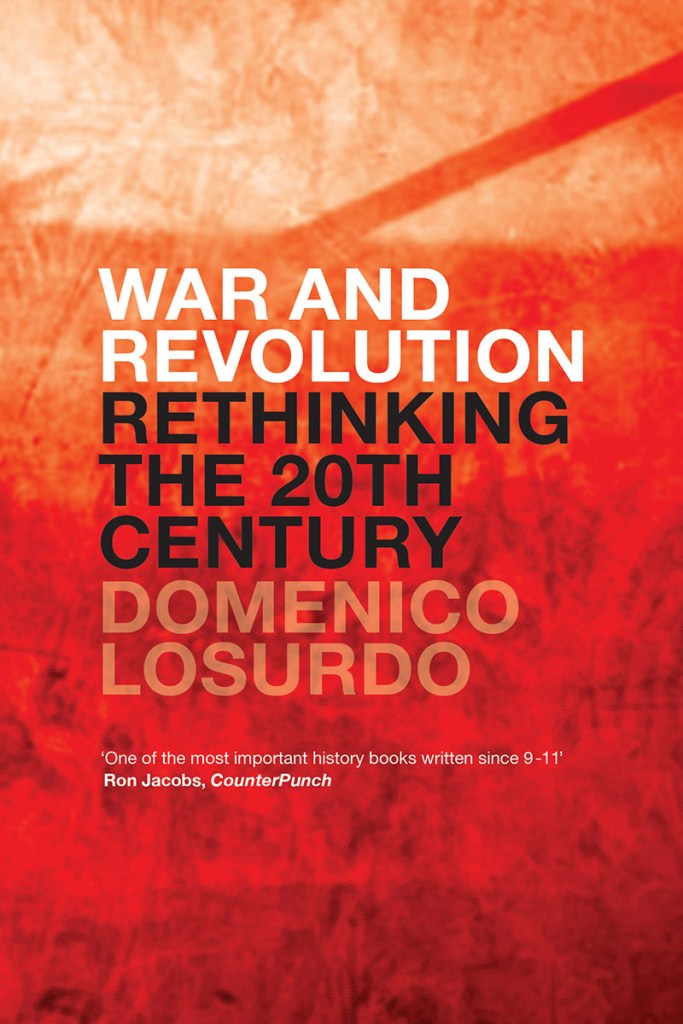

Domenico Losurdo, War and Revolution: Rethinking the 20th Century, Verso 2015, p 313

In 2013 Russell Brand made a call for revolution which gained a popular echo. For a while Russell Brand’s debate with Jeremy Paxman was a reference point for a growing anti-austerity left that later rallied around Jeremy Corbyn.

Comedian Mark Webb, ‘the other one from Peep Show,’ responded to Brand with a very patronising open letter that ended with the words: ‘We tried that [revolution] again and again, and we know that it ends in death camps, gulags, repression and murder. In brief, and I say this with the greatest respect, please read some fucking Orwell.’

It’s funny how Webb thought that 1984 and Animal Farm were actual history books. But the most obnoxious part of the letter was the claim that revolution leads to (in the words of Monty Python) ‘blood, devastation, death, war and horror.’ This claim relies on the complete erasure of all the nasty parts of the history of capitalism and liberal democracy. It is a claim rooted in a long-standing historical tradition of tracing all the evils and horrors of the 20th century to revolution. It is precisely this claim that the late Domenico Losurdo challenged in his 2015 book War and Revolution: Rethinking the 20th Century. The author passed away in 2018. This book is a great monument to leave behind.

Imperialism

Losurdo shows how Europe’s empires were practising discrimination and mass violence long before the October Revolution. JA Hobson drew attention to the genocide of African Bushmen and Hottentots, Indigenous people in the Americas and Maoris. The Boer war saw tens of thousands die in British concentration camps; Spain’s war in Cuba and the USA’s war in the Philippines also saw the use of concentration camps. In the Belgian Congo a ‘civilising crusade’ became a merciless campaign of extermination that claimed ten million lives. In the 1904-1907 Herero rebellion German authorities shot the armed and the unarmed, men, women and children.

Losurdo, who is a historian of ideas, accompanies his account of imperial crimes with an account of the justifications that accompanied them. Ludwig Gumplowicz in Der Rassenkampf (1909) justified genocide, referring to Native Americans, Hottentots of South Africa and Australian aborigines. Theodore Roosevelt claimed that the only good Indian was a dead Indian and justified genocide ‘if any black or yellow people should really menace the whites.’ The idea of an ‘ultimate solution to the Negro problem’ was a topic of public debate in the USA before World War One. For Ludwig Von Mises, poor people and ‘savages’ are ‘dangerous animals.’

Going back further, Locke defended slavery and the genocide of ‘Irish papists’; Jefferson harped on the theme of the ‘inferiority’ of blacks, John Stuart Mill demanded ‘absolute obedience’ of ‘races’ in their ‘nonage’ and celebrated the Opium Wars.

Chinese defences during the Second Opium War (1856-1860). The European powers fought this war to force the Chinese to import opium.

All this, you may have noticed, was long before the October Revolution. And it was said and done not by radicals on the left but chiefly by people on the liberal wing of the political establishment.

Reactionary historians

Return briefly to Webb’s open letter and note that it talks about ‘death camps’ and ‘gulags’ in one breath, implying that Nazism and Communism are linked, are both the results of ‘revolution.’ This is another idea tackled by Losurdo. He traces it to right-wing historians like Furet, Nolte and Pipes, who argued that the revolutionary tradition was somehow ‘responsible’ for the rise of Nazism. For reactionary historians, the 1917 October Revolution broke previously sacred moral taboos, above all the use of violence and discrimination against particular groups in society (‘de-specification’). Attacks on rich people and aristocrats, in this schema, open the door to attacks on ethnic minorities.

But War and Revolution demonstrates with a thousand examples that the old regime (the capitalist world order, not just Tsarist Russia) had long since broken every one of these supposed taboos a thousand times and on a greater scale. Fascism and totalitarianism were not in any sense inspired by the Russian Revolution (except insofar as the victim can be said to ‘inspire’ the attempted murder); fascism had its origin in imperialist violence, in the ‘total mobilisation’ around World War One, and in traditional hierarchies.

De-specification at home and overseas

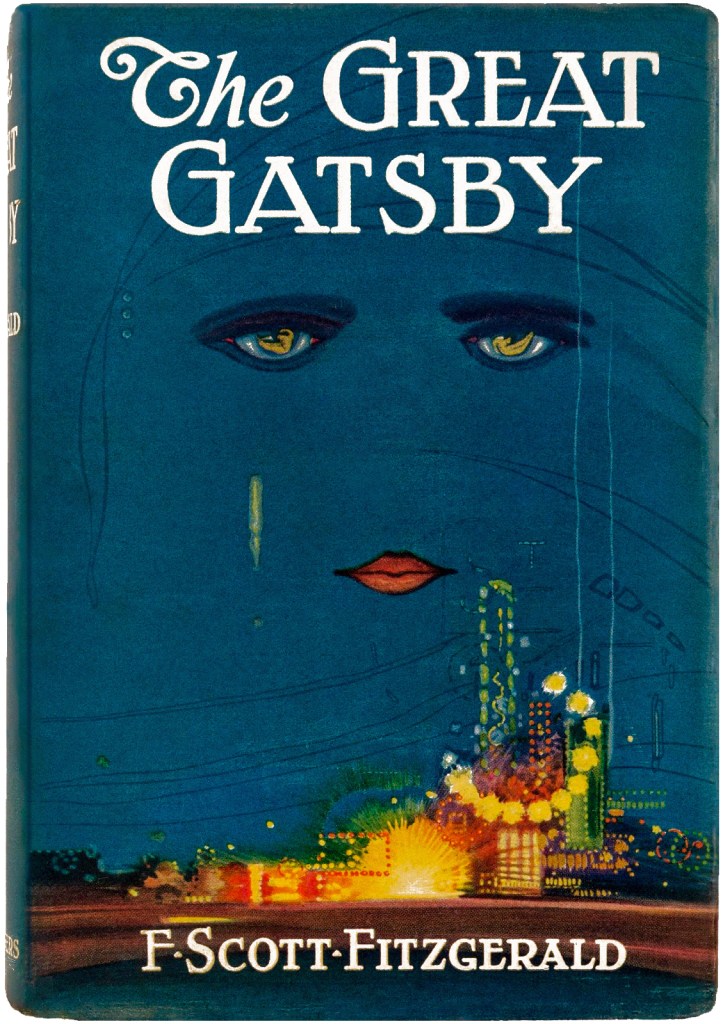

All the grisly categories and keywords of the Nazi Third Reich were invented in ‘liberal’ Britain and the US: concentration camp, untermensch, final solution, miscegenation, ‘race-hygiene’, war of extermination.

For example Lothrop Stoddard (cited as ‘this man Goddard’ by Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby) published The Menace of the Under Man in 1922, warning of the social and ethnic threat of ‘inferior races’ and popularising the term which became untermensch. Racial and class hatred went hand in hand: it was a widespread belief among the rich that poor people were poor because they were ‘racially inferior.’ 13 US states had laws for compulsory sterilisation before World War One.

‘Have you read ‘The Rise of the Colored Empires’ by this man Goddard?…The idea is if we don’t look out the white race will be – will be utterly submerged. It’s all scientific stuff; it’s been proved… This fellow has worked out the whole thing…’

-Tom Buchanan in The Great Gatsby, Chapter 1

The imperialist tradition was explicitly cited as an inspiration and justification for Hitler’s war in Eastern Europe and for Mussolini’s war in Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Hitler argued that Germany had every right to do to the Slavs what the USA had done to Native Americans and what the British had done to India.

The continuities between imperialism and fascism are obvious, clear and undeniable. The most we can concede to defenders of capitalist democracy is that the fascists took imperialist ideas to extremes.

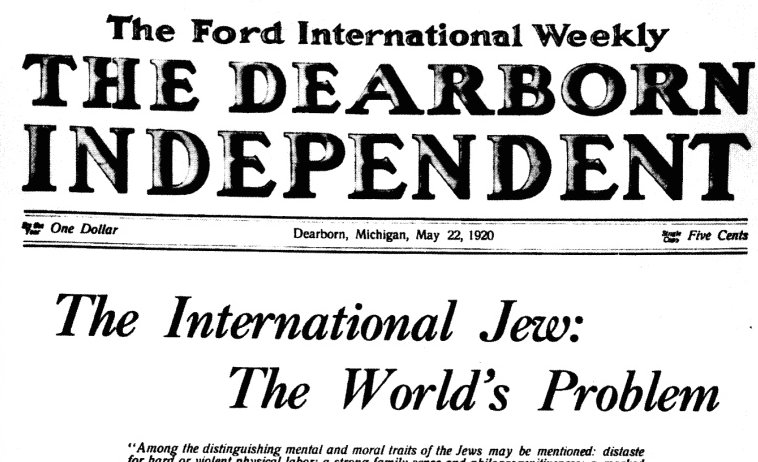

And the continuities between capitalism and fascism go further. To take just one example, arch-capitalist Henry Ford directly inspired Hitler with his anti-Semitic newspaper the Dearborn Independent.

Even if we pretend that imperialism never happened, Losurdo exposes what was in reality ‘master race democracy.’ How many of these liberal democratic states in 1910, or even in 1950, really had a ‘one person, one vote’ system? Women and those who did not own property (ie, the majority) were excluded. Assassinations and massacres of striking workers were commonplace (and still are – see Marikana and Zhanaozen in 2012).

The Challenge of October

Racial, gender and anti-worker discrimination were normal and all-powerful, backed by lethal force and explicitly defended by mainstream liberal politics in the year 1917. The October Revolution opposed all three.

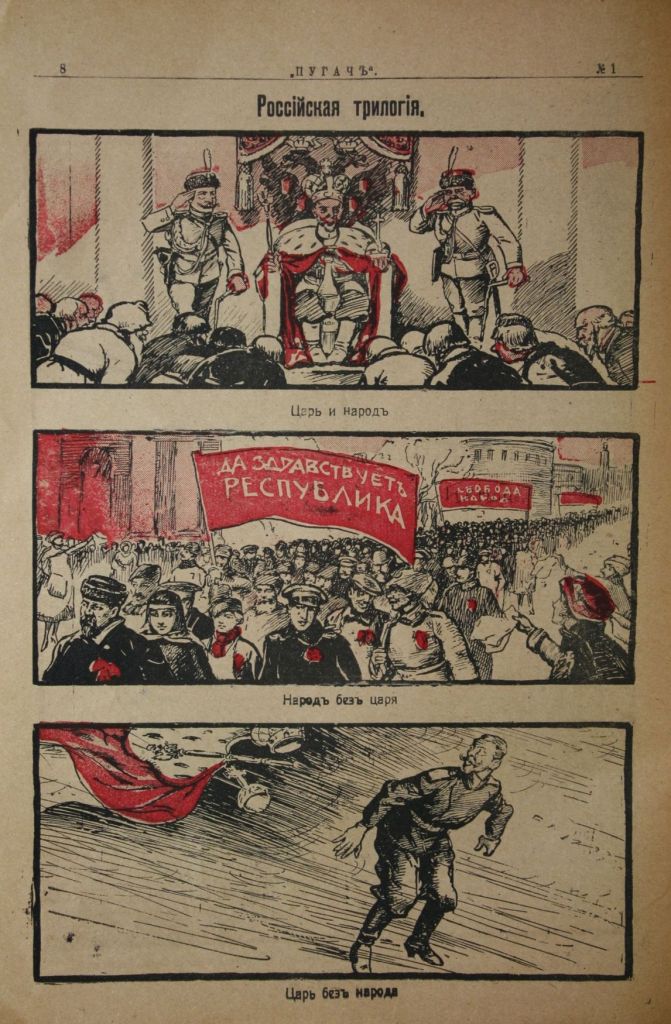

The more moderate socialists, some grudgingly (like Kautsky) and some enthusiastically (like Lensch), made their peace with imperialism. Only Lenin and other ‘extremists’ like him kept up the attack on imperialism and discrimination consistently. The October Revolution appealed to colonial peoples, workers and women to revolt. It was therefore branded as an expression of the ‘barbarism’ of ‘inferior races’ and as a ‘Judeo-Bolshevik conspiracy.’ Class hatred was inseparable from race hatred. I have read news reports from the time which claimed that Lenin was Jewish and that the soldiers who supported him were ‘chiefly Letts and Chinese.’ The Nazis were fired up by these wild racial conspiracy theories into a frenzy to annihilate communists at home and abroad.

‘Far from being attributable to the October Revolution,’ says Losurdo, the key features of Nazism ‘derived from the world against which [the October Revolution] rebelled.’

World Wars

We have seen how the ‘democracy’ of the early twentieth century was in fact saturated with violence and racism. The coming of World War One brought about a ‘mutual excommunication from whiteness’ among the European powers: suddenly the ‘Slavs’ were ‘Asiatic,’ there was talk of ‘Black France,’ and Germans were ‘Huns’ and ‘Vandals.’

The world wars ushered in all the features of dictatorship and totalitarianism: collective punishment of populations, firing into crowds, the punishment of deserters’ families, propaganda and strict control of information, and ruthless persecution of groups and individuals opposed to the war. Repression came from above, brutal mob violence from below: Germans were attacked in the USA and UK. The Turkish state carried out genocide against Armenians. Tsarist Russia persecuted the Jews of occupied Galicia, then during the Civil War the counter-revolutionary White Russians murdered between 50,000 and 200,000 Jews in Ukraine. Japanese-Americans were imprisoned in concentration camps for the duration of the Second World War. Whole cities were levelled by both sides, hundreds of thousands of their occupants killed.

So we don’t have to cook up far-fetched arguments about how communists invented totalitarianism; they had no need to. Liberal democracy had already perfected it.

Losurdo debunks with great flair the Black Book of Communism, a work that made the case that ‘communism’ killed 100 million people and was worse than Nazism. He deconstructs the category of ‘man-made famine’ and the claim that a government’s political responsibility for a famine constitutes ‘genocide.’ Britain blockaded Germany in World War One, and kept up the blockade even after the armistice was signed, condemning many to death from hunger and disease. In the very same way Britain and France enforced artificial famine on the red-controlled areas of Russia during the Russian Civil War. Famine has remained in the arsenal of capitalism as a weapon of war, used against Iraq in the 1990s leading to the deaths of half a million people, most of them children. These atrocities are never recognised as ‘man-made famine.’ It appears it’s only man-made famine if it happened in Russia after 1917 or in China after 1949.

The Revolutionary Tradition

To demonstrate the hypocrisy of liberal attacks on socialism is a great achievement. A broad spectrum of socialist opinion can read Losurdo and cheer him on. But we live in a historical interregnum – after the manifest bankruptcy and collapse of the two giants of social democracy and Stalinism, and before the rise of the next great challenge to capitalism. Confusion and disagreement prevail. I read in Losurdo’s obituary some uncomfortable facts about his politics that, having read this book, I didn’t know but am not too surprised to learn.

His defence of the revolutionary tradition is more divisive than his attack on liberalism. Without spilling too much ink on it, I think he is too critical of the October Revolution and too uncritical of the Stalinist tradition. In fact, he does not acknowledge any rupture or distinction between the two. The book attacks liberal democracy on its own terms, and presents a modest defence of revolutionary socialism on the same terms. But it does not go on the offensive; it makes no case for an alternative model of participatory working-class democracy, that is Soviet democracy. This is a serious shortcoming that weakens the analysis. Absent is any analysis of what went wrong with the Soviet Union. How did a supposedly ‘socialist’ country end up presiding over the hunger and terror of the 1930s? People want a serious answer.

Conclusion

In school, they taught us the history of the early 20th century in the simple binary terms of ‘Dictatorship and Democracy.’ On the one hand there were dictatorships, and within that category there were Communist and Fascist dictatorships. The Dictatorships were opposed by the Democracies. Most of the world was excluded from this schema: old regime monarchies, conservative bourgeois dictatorships, semi-colonies and colonies apparently did not exist. Imperialism was never acknowledged. When Word War Two rolled around, it was never explained why, all of a sudden, the British were to be found fighting in Singapore and Egypt, the Americans in the Philippines, etc.

Stacked up against even a single chapter of Losurdo’s War and Revolution, the contention that ‘revolution ends in death camps, gulags, repression and murder’ is not tenable. All existed long before anyone ever revolted against capitalism. These revolts were attempts to end these horrors. The rules of liberal democracy, so pristine and perfect in the abstract, were in practise not applied to the majority of humanity or in times of war and crisis.

Not only was this a historical reality, it was explicitly defended and theorised by supporters of liberal democracy at the time. And it has not changed. This is not just in the past, but in Webb’s own present-day Britain, under Labour and Tory alike: in Iraq and Yemen; in Grenfell tower; in prisons, among the homeless and refugees; in the rigid discipline, terrifying precarity and back-breaking toil of low-paid workplaces. And all that is just attacking liberal democracy on its own terms. In the light of all this, it should be clear that to defend the status quo is to defend ‘death camps, gulags, repression and murder.’