In January 1918, a few months after the October Revolution in Russia, a parliament called the Constituent Assembly met for one day before it was suppressed by the Soviets. This blog has dealt with the episode before. The incident suggests a ‘What if?’

In OTL (Original Timeline, ie, real life), the Soviets were willing to allow the Constituent Assembly (CA) to exist as a subordinate body. Likewise the CA was willing to let the Soviets exist as a subordinate body. But neither would tolerate the other attempting to assume state power.

But what if the Soviets were willing to bend the knee? What if the Constituent Assembly was allowed to assume control? How might the Russian Revolution and Civil War have developed from there? How might the Russian Twentieth Century have been different?

Element of Divergence

First we should explore plausible scenarios where this could take place. We should answer the question of why and how it might come about that the Soviets, having seized state power, would be willing to hand it over to the CA.

The Soviets were workers’ councils, a system of direct participatory democracy. The Bolsheviks Party had won a decisive majority in these councils in September 1917. They believed that the Soviet was a higher form of democracy than the CA. They hated the Right Social Revolutionary party (RSR), which over 1917 had made compromises to the right and enacted repression against the left. They believed that the split between the RSRs and the Left SRs rendered the election results meaningless.

In other words, the Bolsheviks (along with their allies the Left SRs) had strong reasons to suppress the CA.

In spite of these strong reasons, it is not that difficult to imagine the Soviets giving up power to the CA. In Germany and in Austria in this period, and in Spain in the 1930s, we see many examples of communists, socialists and anarchists giving up power to a bourgeois-democratic government in exactly this way. In fact, they were far more flagrant. The German Social Democrats assembled militias of far-right veterans to suppress the German Revolution. The Communists in Spain became the enthusiastic apologists of a liberal-republican government and preached that Spain was not ready for revolution. In short, the Bolsheviks are the outlier among social-democratic and even nominally communist parties in the Twentieth Century in that they were really willing to seize and hold power.

In our ATL (Alternative Timeline), the leadership of the Soviet is more in line with the mainstream of international social democracy – ie, more timid and cautious.

I do not propose a single ‘Point of Divergence’ – for example, Lenin is murdered by agents of the Provisional Government; Trotsky stays in a British concentration camp in Canada. Rather I propose an Element of Divergence, a factor which develops differently over a whole period of years and even decades. In this ATL, the Bolshevik Party as we know it simply do not develop. The more radical and militant trends within the Russian Social-Democratic and Labour Party (RSDLP) do not cohere into the Bolshevik party from 1903 to 1912; rather they remain loose and scattered and undefined. We will, for convenience, refer to them as the militant socialists.

The Alternate Timeline

Pushed by a mass upsurge of workers, soldiers, sailors and peasants, the militant socialists end up in control of the Soviet by October 1917. They proceed to seize power in some incident corresponding to the October Revolution. But by January they are afraid of their own power and uncertain what to do with it. Their own base – workers and poor peasants – feel the hesitancy from above and demoralisation begins to set in. Meanwhile the militant socialist leaders feel pressure from the Russian ‘intelligentsia’ (professional middle classes) which supports the RSRs and the CA.

Instead of shutting down the CA after a single day, they remain in it, trying to negotiate a strong position for the Soviets within a new CA-dominated political regime. In other words, they turn back the clock and accept Provisional Government Mark 2. The discredited Provisional Government, attacked from right and left then finally overthrown in the October Revolution, has returned in a new guise with many of the same personnel.

Thus begins the Chernovschina – the regime of Viktor Chernov, a firebrand within the RSRs who in OTL served for that one day as President of the Constituent Assembly.

Chernovschina

In OTL, the RSRs set up a government at Samara during the Civil War in the name of the Constituent Assembly. This government was called Komuch. It gives us valuable insights into the main features of the all-Russian Chernovschina which develops in this ATL.

The Chernovschina, like Komuch, would have a narrow base of support: a layer of the intelligentsia, and not much beyond that. Its decisive majority vote in the CA elections may seem to indicate that it had a mandate. But for Komuch, this mandate translated into precisely nothing. It was unable to raise an army. It suppressed the Soviets on its own territory and gave back the industries to their capitalist owners; still the wealthy refused to support it.

Komuch governed a population of 12 million people on the Volga. Chernov would govern all of Russia, including the central industrial region where the factory workers in their millions are enthusiastic supporters of the Soviet. In these central provinces and great cities, the Bolsheviks actually won a majority in the CA elections. Unlike Komuch, the Chernovschina would be able to present itself as having the support of the Soviet; this and this alone, the support (really the submission) of the Soviet, explains why it is in power.

It has a tense relationship with the Soviet, with the working class, with the poor peasants. But the militant socialists are forced to act as the enforcers of the Chernovschina. They try to whip their supporters into line, because to do otherwise would be to admit their own bankruptcy.

As in OTL, famine begins, striking the cities hardest. Chernov refuses to consider the kind of expropriations which the Bolsheviks practised in OTL; thus he retains the passive support of the peasant majority, but loses the active support of the cities.

Thus the working class, its hopes raised high by the October Revolution, feels a horrendous demoralisation set in as 1918 advances. Many still hold out hope that the Chernovschina will deliver for them, or that the Soviet might yet overthrow the CA. On that basis, Chernov is still able to mobilise some support.

Civil War

And support he needs. The Russian armed forces, though in an advanced state of collapse, are fighting a desperate war against Germany. Meanwhile in ATL as in OTL, military officers, nobles, the bourgeoisie and the church organise counter-revolutionary armies. They see the RSRs as little better than the militant socialists; in any case, the militant-socialist bogeyman is an integral part of the Chernov coalition. Alongside the new Russian army which Chernov is trying to build, the Red Guards are the main armed force on which the CA can rely.

And Chernov himself, as in OTL, supports the seizure of noble land by peasants. The emergent White Guards have no reason to be less hostile to the RSRs than they were to the Bolsheviks in OTL.

It is frankly impossible to see how the Chernovschina can win the war against Germany, or even to hold out until Germany’s defeat in the West. But as in OTL, they are determined to continue the war. We must envisage an inexorable German advance to the gates of Moscow itself, even the fall of Petrograd, before the RSRs are forced to sign a peace treaty even more humiliating than the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

The Allies, meanwhile, look askance at the Chernovschina for the same reasons the Whites do: the communist bogeyman. Initially they support Chernov against Germany, but then turn against it when the peace treaty is signed.

So we end up as in OTL: White armies, backed by the Allies, fighting against the ‘Red’ (perhaps the ‘Pink’) regime of Chernov. The Allies might be less enthusiastic about intervention because the Chernov regime is more amenable to them – paying the debts and not seizing the factories. It is possible the Allies, or at least some of the Allied countries, would remain neutral. But on the other hand the Allies would not be held back by their own people. In OTL, there was deep support for the October Revolution among working-class people in the western countries, resulting in the ‘Hands off Russia’ movement and the Black Sea mutiny. These factors tied the hands of Allied intervention. It is doubtful the western working class would be as sympathetic to the Chernov government, so the Allies’ hands would not be tied in the same way.

The Fall of the Constituent Assembly

Increasing discontent in the ranks of militant socialists at some point breaks out into a mass uprising against Chernov in Moscow. Meanwhile Chernov and co have grown impatient with the Soviet; they see it as the main obstacle to Allied support. So the Chernovschina engage in the bloody suppression of the uprising of the Moscow proletariat. This results in the final liquidation of the Red Guards and the Soviets, and the final demoralisation of the working class. The Revolution is over.

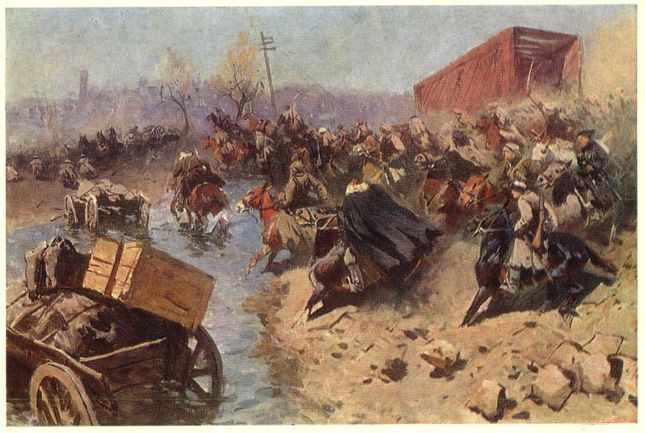

The Chernovschina tries to fight on, but its people are utterly demoralised and it is beleaguered on all to sides. It succumbs to the onslaught of the White Armies. The death-blows are probably dealt in the campaigning seasons of Spring and Summer 1919.

So this ATL leads us to a White victory in the Russian Civil War. That is a ‘What If’ for another day and another post. But suffice it to say that a White military victory would only be the beginning of the violence. The White movement, in order to fulfil its aims, would terrorise the urban population into submission and seize the land back from the peasants. The scene would be set for decades of conflict as the White generals invade the newly-independent republics one after another, trying to restore their vision of ‘Russia one and indivisible.’

Conclusion

This alternate history is based on two main real-life analogues: Komuch (which I have written about here, here and here) and the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War.

For some, it is tempting to imagine that the CA might have led Russia to stable parliamentary democracy, averted civil war, etc. But an electoral majority does not invest a political party with magical powers. In terms of sheer numbers, the RSRs won an overwhelming vote. But the vote was confused and passive in character. They had a very narrow base of confident, active supporters. The CA could only have survived if the Soviets had made the terrible mistake of propping it up at their own expense – at their own very great expense.