Full-scale war breaks out between the young Polish Republic and the young Soviet Union. This is Episode 25 of Revolution Under Siege, an account of the Russian Civil War. We are approaching the half-way point in the fourth and final series.

The Bloodless Front

Readers will remember the young Red Cossack Vasily Timofeich Kurdyukov, whose father was a White Guard but who himself joined the Reds along with his brothers. Vasily – I hope Isaac Babel, who recorded this story, changed the names, but let’s call him Vasily – was a witness to the murder of one brother by the father. Is this ringing a bell yet? He was there too when, after the defeat of Denikin, he and his brothers tracked down their father in Maikop and killed him in retaliation despite the protests of the ‘Yids’, by which Kurdyukov meant the Soviet officials.[1]

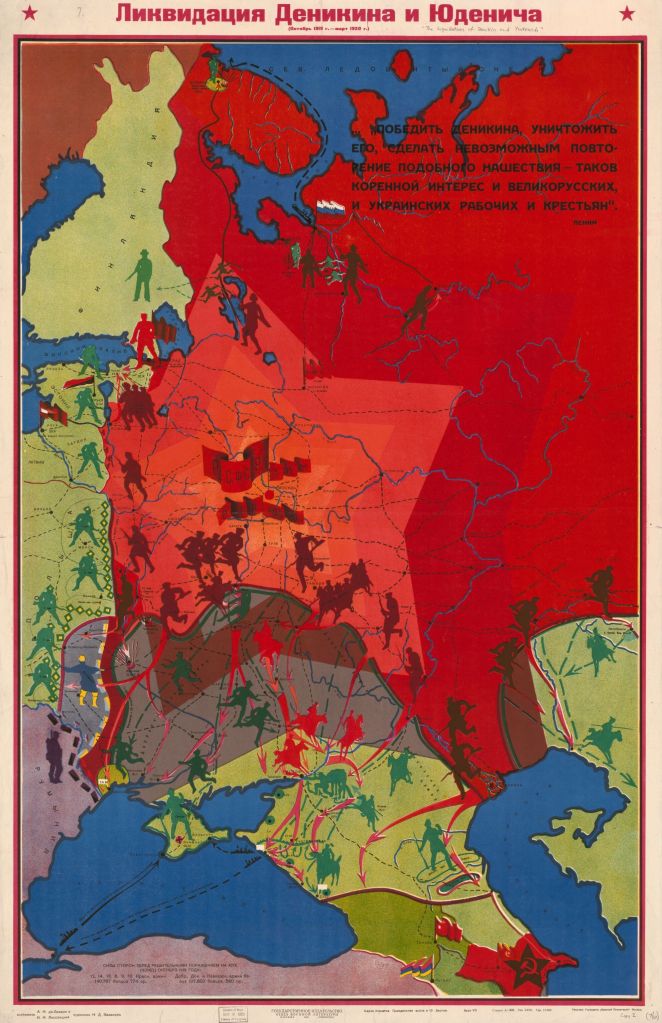

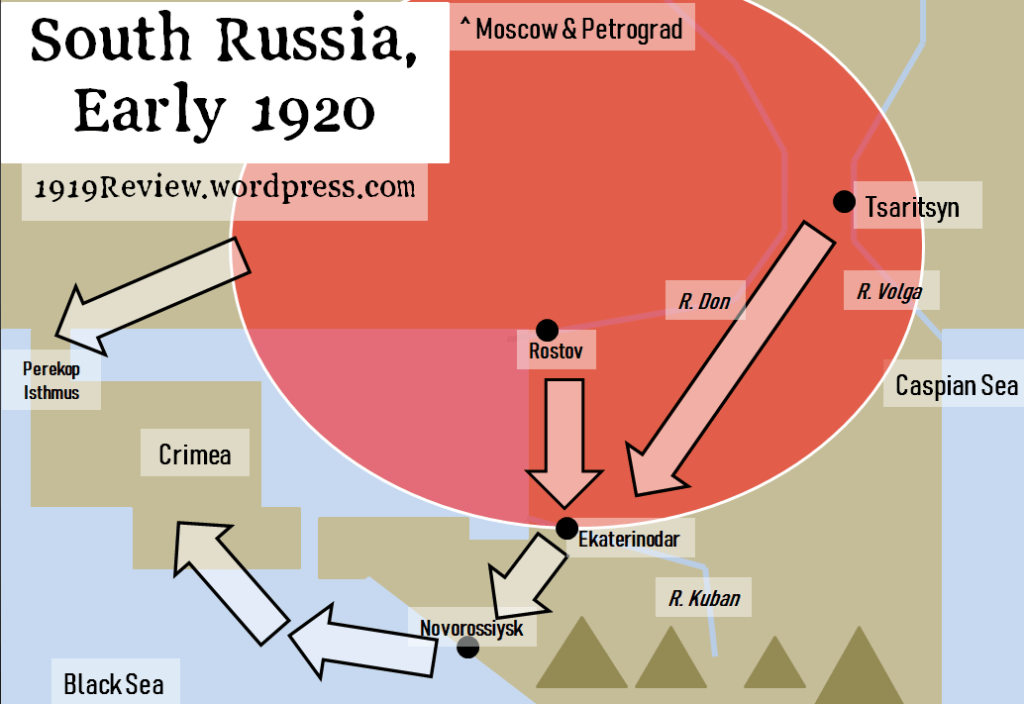

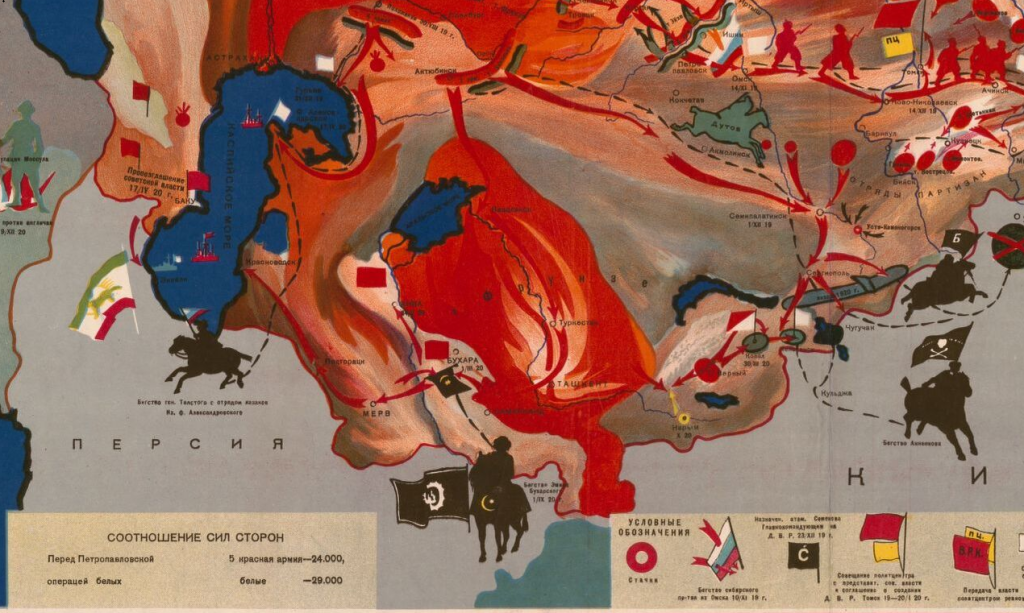

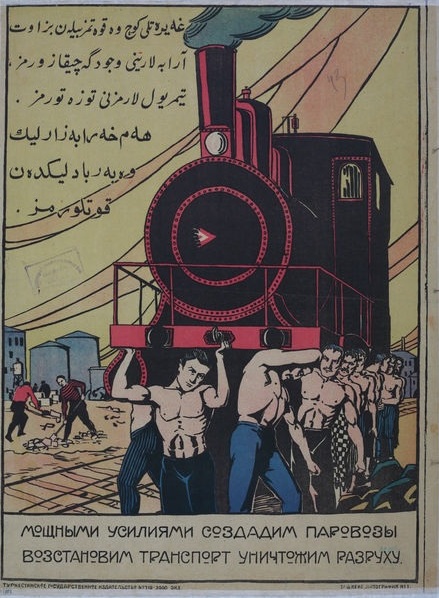

April 1920 found VasilyKurdyukov on the move. Denikin was, along with Timofei Kurdyukov, vanquished. So Vasily, his older brother Semyon, and 16,000 other members of Budennyi’s First Red Cavalry Army had left South Russia, going from Maikop through Hulyaipole. They were making their way across Ukraine to take part in another campaign, covering 1200 kilometres in 30 days. Compared to the epic struggle against counter-revolution that was behind them, nothing too serious or historic appeared to lie ahead. The war was over, bar the fighting in parts of Siberia, the Caucasus and Central Asia. The political regime seemed to be opening up, loosening up. The Allies lifted the blockade in January. The death penalty had been abolished. The leaders in the Kremlin were discussing post-war reconstruction, not the starting of new wars. Back east in the Urals, Third Army had laid down their rifles and turned to chopping down wood as the first Labour Army. 7th Army, after routing Iudenich near Petrograd, began digging peat. ‘Communiques from the bloodless front’ announced the rebuilding of this bridge or that railway line, the numbers of locomotives repaired, etc. And throughout the Red Army, literacy classes were a day-to-day reality, with thousands of mobile libraries in operation. As Kurdyukov rode, he would have been able to read educational letter-boards on the backs of the riders in front of him. [2]

For most Red Cossacks and for the large minority of worker-volunteers in the Red Cavalry, we can assume that peace couldn’t come soon enough. The fields of the Don and Kuban had been tended largely by the women and the old men since 1914. But we can easily imagine that for some Cossacks who had been at war for six years, life in the saddle with a sabre was the only life they had known as adults.

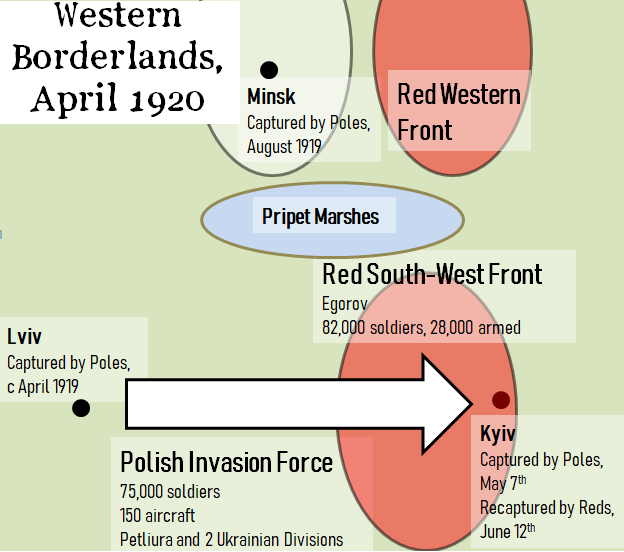

The First Red Cavalry Army was going west to join up with the Red South-Western Front under Egorov. They would then grab a few Ukrainian towns from the Polish Army, so that when the Soviets and Poland finally got around to signing their peace treaty, the line on the map would be a little further west and the Ukrainian Soviet Republic that bit bigger.

So far, the Poles had been having their own way – defeating the Ukrainian Nationalists in Galicia and seizing from them the city of L’viv (which they called Lwów and the Russians called L’vov, and which is today part of Ukraine); and to the north, beyond the Pripet marshes, the Polish forces had been chipping away at the Soviet border for a year, seizing one Belarussian town after another. But now that Denikin and Kolchak were finished, it was time to hit back. In a few weeks or a month – if peace with Poland hadn’t been signed by then – the Red Army would be ready to launch an offensive, to hammer that border into a more agreeable shape.

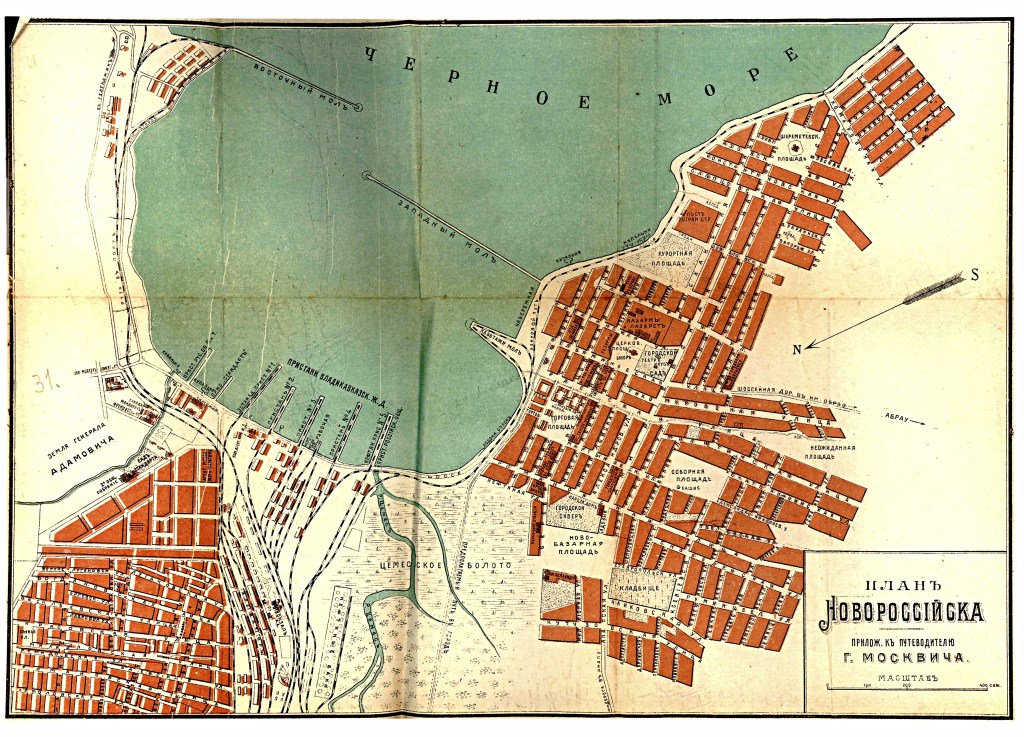

But on April 24th 75,000 Polish soldiers invaded Soviet Ukraine. 11,000 fighters lately incorporated into the Red Army mutinied, led by their commanders, and went over to the Poles. The Polish government had signed a treaty with Petliura, the leader of the late Rada, and he and two divisions of Ukrainian soldiers were aiding the invasion. To make matters worse, Makhno chose this moment to strike the Reds: on 25 April his guerrillas massacred a regiment of the Ukrainian Labour Army at Marinka on the Donets. They also blew up bridges around the Kyiv area, crippling transport.

The Polish invasion made swift progress. This was no border skirmish. They were well-armed. Motor trucks infiltrated Red lines on small country roads. 150 planes supported them from the air with devastating attacks on armoured trains and on flotillas on the Dnipro river. There were 82,847 Red Army personnel on the whole South-West Front – but only 28,568 of them had weapons, and they were in disarray. Egorov pulled back his troops rapidly. The Poles gained 240 kilometres in two weeks. On May 7th they took Kyiv, and soon they had bridgeheads east of the Dnipro River. Since April 24th they had suffered only 150 fatalities.

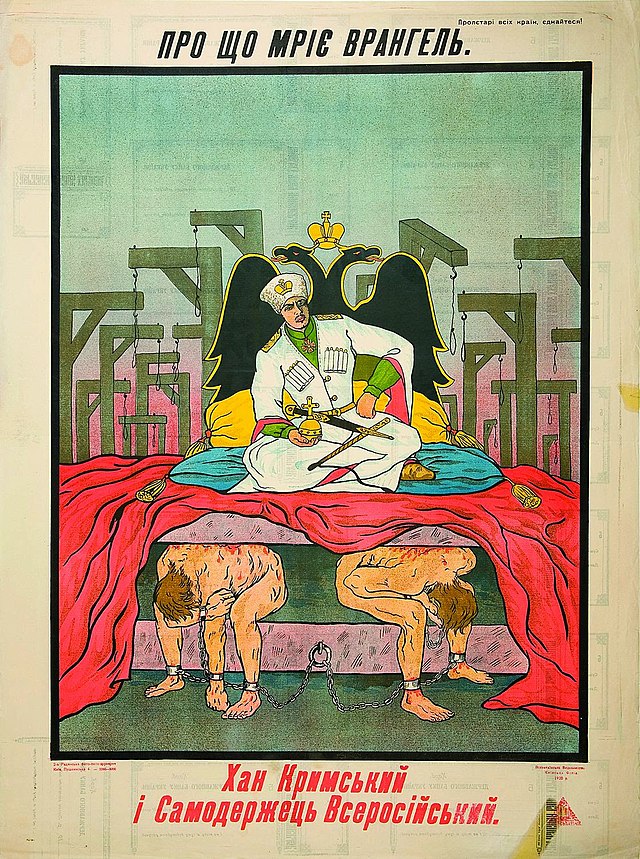

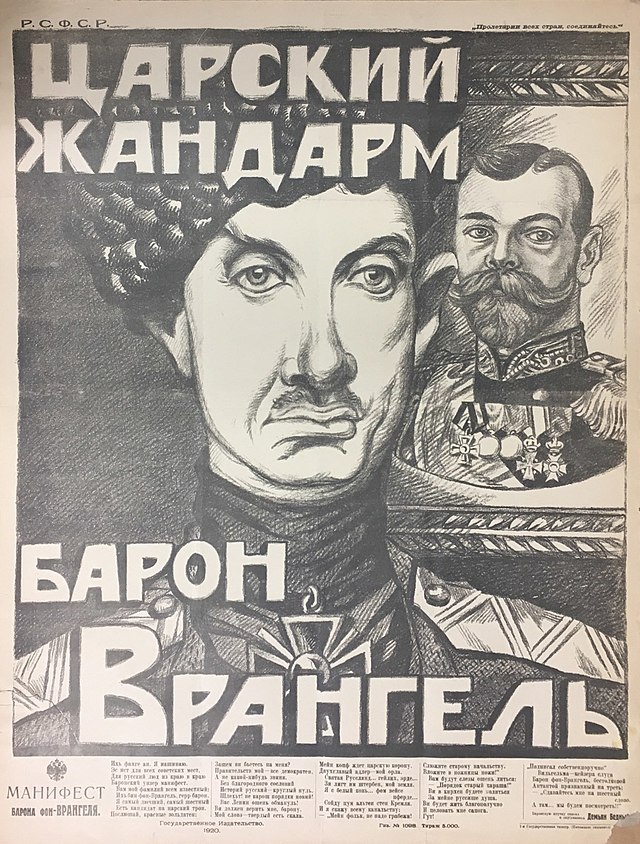

Less than one month later, the White Guards who had found refuge in Crimea began an assault on Ukraine’s mainland. Wrangel’s 35,000-strong ‘Russian Army,’ which contained many of the same officers and Cossacks who had been fighting Soviet power since 1917, had rejoined the fray. Two new fronts had opened up, and the prospect of peace had receded to the very distant horizon.

At War Again

We can imagine the dismay and fear now felt by people in the Soviet Union, from the Kurdyukov brothers in Budennyi’s ranks to their mother back in South Russia. Just when the country was escaping, at long last, from the realm of war, here was another massive foreign intervention. It would set off the dreadfully familiar cycles of confusion, fear, revolt, hunger, disease, red and white terror. The death penalty was soon restored. The railways were militarised.

In the words of John Reed:

The cities would have been provisioned and provided with wood for the winter, the transport situation would have been better than ever before, the harvest would have filled the granaries of Russia to bursting – if only the Poles and Wrangel, backed by the Allies, had not suddenly hurled their armies once more against Russia, necessitating the cessation of all rebuilding of economic life – […] the concentration once again of all the forces of the exhausted country upon the front.

In the words of Trotsky: ‘Ahead of us lie months of hard struggle… before we can cease to weigh the bread-ration on a pharmacist’s scales.'[3]

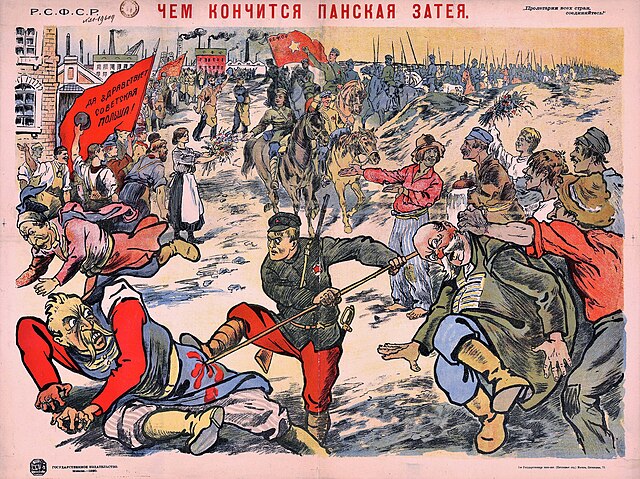

This time there was also a strong element of patriotic indignation. A repeat of the Polish invasion of 1612 was widely feared. The famous tsarist General Brusilov came out of hiding and volunteered his services as an advisor to the Red Army.

Communists, from the Politburo in the Kremlin down to the volunteer in the trenches, found themselves trying to rein in patriotism whenever it threatened to spill over into the familiar Tsarist channels of imperialistic contempt for the Polish people. Trotsky and Lenin were scrupulous about never speaking of ‘The Poles’ or ‘Poland’ but only ‘The White Poles’ or the ‘Polish landlords.’ ‘Do not fall into chauvinism,’ urged Lenin. One Red Army paper, Voyennoye Dyelo, got into big trouble. Officers were sacked from the editorial board and the paper was suspended over the use of the phrase ‘the innate jesuitry of the Polacks.’

Trotsky affirmed that ‘defeat of the Polish White Guards, who have attacked us will not change in the slightest our attitude concerning the independence of Poland.’

Ukrainian communists, too, made appeals for the defense of Ukraine as a nation. A common charge was that Petliura was the chosen caretaker of the Polish landlords, to mind the Ukrainian estate which they had their eyes on. [4]

The rest of this post will explore the background to the invasion from the perspective of the Polish Republic, then describe the initial Soviet response.

Intermarium

With the defeat of Germany in November 1918, a strong Polish military force emerged. Four of the combatant empires had large Polish units in their armies – not least a 35,000-strong Polish unit that had been raised in France and was now sent back into Poland. Also important was the Polish unit in the Austrian military, which was led by a man named Józef Piłsudski. The strength of the Polish military is probably what led to the emergence of a bourgeois capitalist Poland instead of a proletarian socialist Poland (though we will look next week at how close Poland came to a socialist revolution).

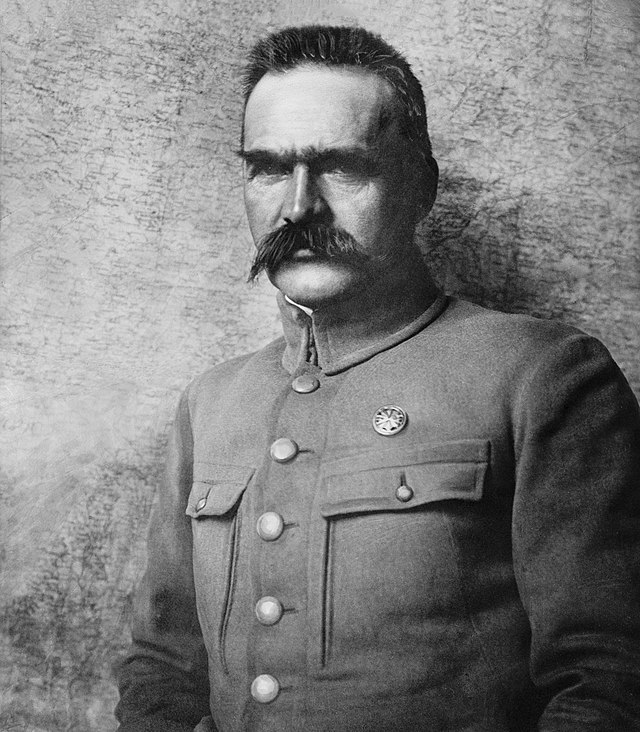

Let’s dwell for a minute on Józef Piłsudski. A Pole from Eastern Lithuania, he grew up under the heavy hand of Tsarist oppression, became a socialist but in his own words he dismounted from ‘the socialist tramcar at the stop called independence.’ He was not a leader of masses but a back-room conspirator and bank robber. [5] Service as an officer in the Polish unit in the Austrian military during World War One promoted him to the front rank of national leaders. In 1920 he was head of state and commander-in-chief of the armed forces. His huge moustache belonged to the flamboyant 19th Century, but his glowering eyebrows and cropped hair gave an impression of urgency and severity.

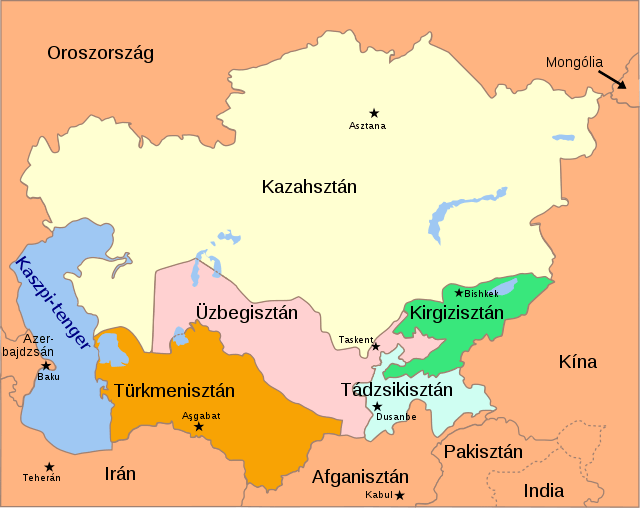

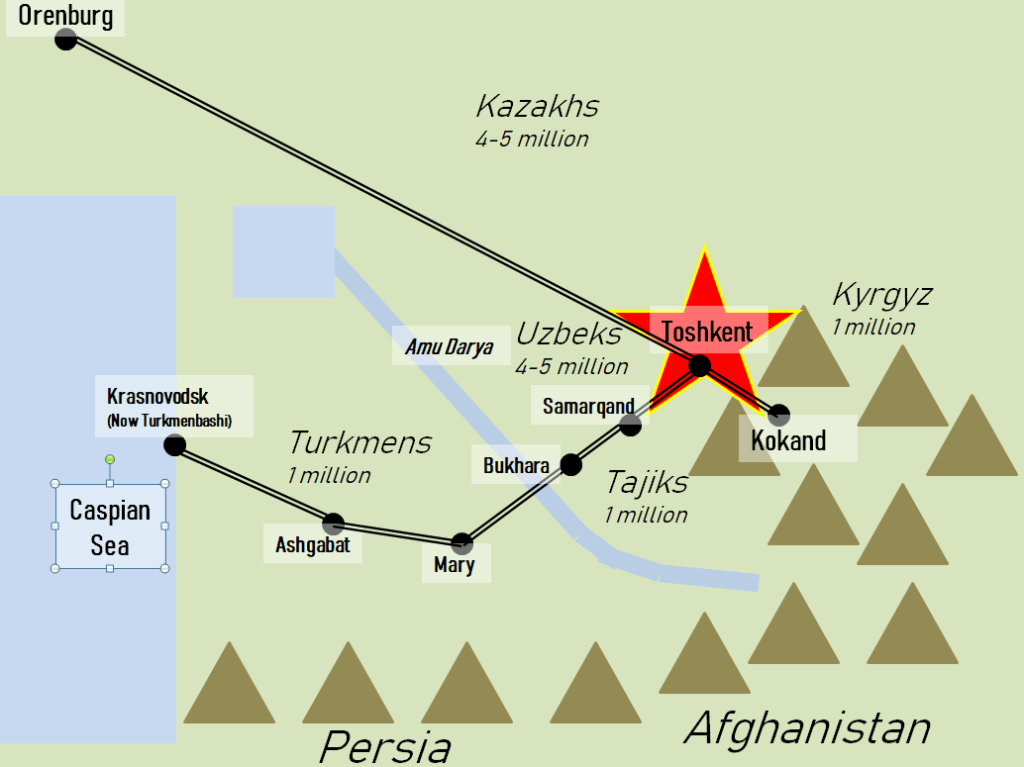

Piłsudski had a vision of what he called Międzymorze, ‘Between the Seas,’ also known as the Intermarium. Without understanding Międzymorze we can’t understand the Polish-Soviet War. The idea was that Poland should lead a federation of countries stretching from the Black Sea to the Baltic – which meant taking over, or at least installing pliable governments in, Ukraine and Lithuania. This idea harked back to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth of centuries past.

But in Poland as in Russia and Ukraine, grand plans had to be put on hold, as famine gripped the countryside and there were years of misery and want. Poland was not torn apart by war as Russia and Ukraine were, but the new Polish state battled with Germans, Czechs and, as we have seen, Ukrainians. Unlike in the Soviet Union, vast amounts of American aid alleviated the situation – in 1919-1920 the American Relief Administration fed and cared for 4 million Poles. By the end of 1919 a strong Polish state was in existence with a population of around 20 million and armed forces numbering 750,000. [6]

The time was ripe for Międzymorze. And the territories of the new Polish empire would be wrestled from the small Lithuanian republic and from the war-weary and ragged Soviet regime.

Toward War

The revolutionary tradition, and most especially those trends around Lenin, had long supported Polish independence, and the Soviet government never made any territorial claim over Poland. An independent capitalist Poland, like Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, would be accepted by Moscow.

Of course, the Soviet Union was in favour of world revolution. But this amounted to supporting communist revolutions and parties in other countries. Military intervention, even in the form of support for indigenous movements, was controversial. As the Brest-Litovsk episode showed, the Bolsheviks’ confidence in world revolution could in the right circumstances make them more amenable to signing a peace treaty, not less, because future revolutionary events would render an unfavourable treaty void.

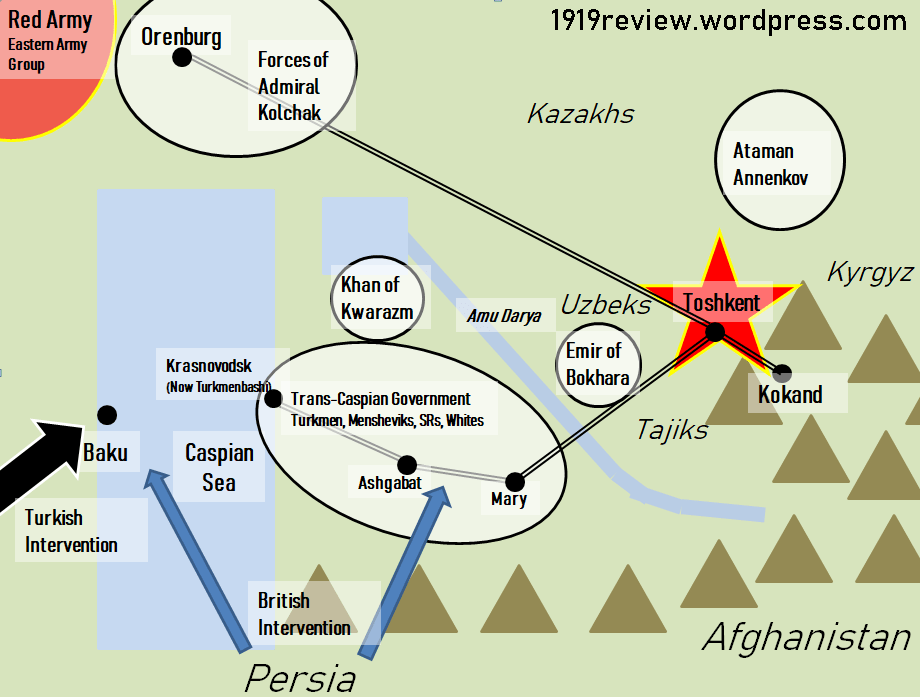

The issue was where to draw the Soviet-Polish border – where, in the ‘300-mile band of polyglot territory between indisputably ethnic Poland and indisputably ethnic Russia,’ [7] would one state end and the other begin? This question had not been on the agenda since the 18th Century, and there was no recognised border. While Soviet Russia was busy fighting against the White Armies in 1919, Poland was settling this question at the point of a bayonet, making steady gains in a small-scale but one-sided war. Galicia was theirs by July 1919.

So the Polish and Soviet armies had been skirmishing for a year before the Polish invasion in 1920. Since the first clashes between Polish and Red troops took place as early as February 1919, the historian Norman Davies accuses other historians of ‘ignoring’ the ‘first year’ of the Polish-Soviet War. [8] It is Davies who here ignores the qualitative difference between the low-level conflict of that ‘first year,’ and the all-out war which began in April 1920 (This is a flaw in his generally great book).

The borderlands between Poland and the Soviet Union can be divided roughly into a northern area around Belarus and Lithuania, and a southern area, Galicia and Ukraine. The Pripet marshes lay in between the northern and southern areas. Polish, Russian and Jewish people lived in both, Belarussian and Lithuanian farmers in the north, Ukrainian farmers in the south.

The possibility of a peace settlement was there. The Soviets had no shortage of competent Polish supporters, some of whom they sent to Poland to try to negotiate peace from late 1918 right up to the eve of the invasion. One typical offer was of territory and plebiscites in exchange for peace. These got off to a bad start when a joint delegation of Soviet diplomats and Red Cross officials visited the Polish Republic soon after its foundation. They were immediately arrested and deported. During their deportation, Polish police dragged them out into the woods and shot them, killing three and leaving one who survived by playing dead. Nonetheless the Soviets kept up their peace efforts through 1919 and into 1920.

Frustration and alarm gripped Soviet diplomats and politicians in early 1920. They were still at the ‘talks about talks’ stage, and the Polish negotiators were stubborn and demanding. They would only agree to meet for peace talks in Barysaw (Borisov), a town recently captured by the Poles. It was not acceptable to the Reds as it was in a zone of active military operations. The Soviets proposed Warsaw, Estonia, Moscow, or Petrograd, all of which the Polish side rejected. Meanwhile Soviet leaders had accepted six out of seven conditions presented by the Poles as a basis for talks, but balked at the seventh – it demanded that they never attack the Ukrainian Nationalist leader Petliura. [9] When Moscow pushed back, Piłsudski broke off talks.

Beevor characterises all this as Piłsudski ‘playing for time.’ The time, from the first Soviet peace mission, was nearly 18 months. Piłsudski ‘s stubbornness is explained by the fact that he did not seek to make peace, but sought a pretext to invade.

‘When diplomatic moves failed,’ writes Robert Jackson, ‘the Reds launched a series of small attacks along their western front; the Poles beat them off and held their positions.’ [10]

The Soviet leaders were not naive, so they understood that a Polish attack was likely. They developed their own plans for a strategic offensive as far as Brest – hence Kurdyukov and 16,000 other riders hurrying over from South Russia. The limit of the Red Army’s ambition was to seize a few more towns before the signing of a peace treaty, and to foil any plans the Poles might have of doing the same.

Unfortunately, some writers highlight a few facts out of context – a troop build-up here, a local offensive there – and paint a picture of a savage communist horde massing to trample and enslave Poland. Piłsudski’s grandiose imperial ambitions, his deliberate wrecking of peace talks, and his very ambitious and large-scale invasion of Ukraine feature only as minor details, if at all. [11]

The Allies

The Soviet leaders were convinced that the Polish invasion was the work of the Allies. It was characterised as ‘The Third Campaign of the Entente’ in an article written by Stalin in Pravda on May 25, 1920. We can say with hindsight that this impression was wrong.

The Allies did not egg on the Poles to attack the Soviet Union. In fact they were shocked and dismayed by the attack. The Allied leaders had learned that the Soviets were not to be trifled with, and they were getting cold feet on the question of intervention. On the more liberal end, Lloyd George thought the Poles had ‘gone rather mad’ and were behaving as ‘a menace to the peace of Europe.’ [12]

The Allies had rejected schemes proposed by Polish leaders which involved the Allies bankrolling a Polish march on Moscow. In addition to their growing wariness toward the Red Army, the Allies still held out hope that the Soviet regime would collapse, and they didn’t want to big up the Poles too much in case it offended a future conservative regime in Russia. Ideally, they wanted Poland to act as a ‘cordon sanitaire’ protecting Germany from the influence of revolutionary Russia – much as Stalin would use it later as a defensive glacis against the west. To that end the Allies began arming Poland in earnest from January 1920: rifles captured from the Austrians, planes and pilots, 5,000 French officers to train them. It was not much compared to the total resources of the Allies. But for a Polish army severely overstretched by its recent conquests, it was a game-changer [13].

In that very important sense, the Soviets were right. The Allies had backed (and still backed) the Reds’ opponents up to this point, and although they did not push Poland into war, in the months and years leading up to the war they backed Poland, armed its soldiers, gave equipment, lent advisors – in short, made the war possible. People on the Soviet side could not have known the ins and outs of Allied policy, and would have been innocent to believe any verbal reassurances along the lines of, Yes, we are bankrolling the army that’s invading you, and we got some other people to invade you a few months ago, but we didn’t actually want this army to invade you right now.

So the Soviets treated it as a seamless continuation of the Civil War. But the fact remains that their strategic understanding of the situation was wrong on a fundamental point. The initiative had come from Piłsudski, not from the Allies.

The Soviets Rally

This was one of several mistaken ideas with which the Soviets were burdened as this war began. But it would take time for these mistakes to have their fatal effects.

The Poles had made their own strategic mistakes in counting on Petliura and the Rada. After a month in Kyiv, things were not going well. Their ally (or ‘caretaker’) Petliura could not rally the Ukrainian people to his cause. It did not help that the price of the alliance was for the Rada to sign away Lviv and West Ukraine to Poland, which demoralised many Ukrainian Nationalists. This was on top of the basic point that Petliura was acting as an ally to the Polish landlords and business owners who had oppressed and exploited Ukrainians.

On May 25th the Reds began their general counter-offensive. At first, the Red Cavalry tried advancing directly on Polish trenches. They rapidly discovered that wild Cossack charges would not work as well as they had against Denikin, and the first few days of the offensive saw little progress. The Poles were experienced at trench warfare, and it was futile to attack them head-on. The Red Cavalry commanders refined their tactics. They would dismount close to the enemy, use artillery, use small striking forces to take strong points; or find gaps in the enemy line, turn enemy flanks, wreak havoc in the rear.

This Budennyi did personally on June 5th. He spent a sleepless night worrying about the following day’s attack, and rose to bad news about one of his divisions being forced to retreat during the night. He personally joined 1st Brigade of 14th Division and led the unit into marshy ground shrouded in early morning mist. They ran into some Polish cavalry, known as uhlans, and gave chase. One uhlan fired at Budennyi and missed. Budennyi caught up to him, knocked him from his horse. The dismounted uhlan fired again, and the bullet whined past Budennyi. The Red Cavalry commander used the flat of his sabre to disarm the uhlan, and brought him in for questioning. This encounter bore fruit: Budennyi learned of an ideal place to cross the Polish trench lines, and even found good places to fire directly down the trenches. The brigade passed through into the Polish rear.

This cavalry infiltration tactic saw widespread success. The area was too large for Great War-style trenches to cover it fully. Zhitomir, far behind Polish lines, was recaptured by the Reds on June 8th. On June 10th the Poles, threatened with being surrounded, evacuated Kyiv. Two or three days later the Reds marched in – this was, Mawdsley points out (p 348) the sixteenth time that the city had changed hands during the Civil War. Fortunately for the residents of the city it was also the last time.

Egorov’s South-West Front had been evacuated quickly enough that they did not suffer major losses during the Polish advance. It showed lessons learned from 1919: let the enemy advance run out of steam, then hit back hard. A Polish veteran summed it up bluntly: ‘We ran all the way to Kiev, and we ran all the way back.’ [14]

As the South-West Front covered the distance between Kyiv and Lviv, the Reds felt the wind at their backs. The insolent invaders were on the run. They might run all the way back to Warsaw. The Polish army appeared to be weak.

Mikhail Kalinin, president of the Soviets, predicted that the defeat of the Polish Army by the Red would deal the first blow to the Polish bourgeoisie, but that the Polish people themselves would deal the second and fatal blow. Likewise Trotsky ‘assumed that Poland would be liberated by her own people… His only recognisable war aim was to survive.'[15]

The Polish defeat, like the Tsar’s, might lead to revolution at home. A fraternal Soviet Poland might help alleviate the horrible suffering in the Soviet Union, might push Germany into revolution, might ignite Europe. The Reds had entered into the conflict with a notion of a struggle over the borderlands. Now they were being tempted by the idea, to use a modern phrase, of regime change.

References

- [1] Isaac Babel, Red Cavalry, Pushkin Press 1926, trans Boris Dralyuk (2014), p 25-26

- [2] Davies,p 118. John Reed, ‘Soviet Russia Now,’ published January 1921 in The Liberator, accessed at Marxists Internet Archive on 10 Jan 2024 at 21:49. https://www.marxists.org/archive/reed/1921/01/russianow.htm

- [3] On the numbers on South-West Front, Makhno, and mutiny of East Galicians, see Davies, p 108. Quote from Reed, ‘Soviet Russia Now.’ Quote from Trotsky, ‘Speech at a meeting in the Murom railway workshops,’ June 21st 1920. In How the Revolution Armed, Volume 3

- [4] Davies, p 115, Smele, p 357, Trotsky quote from ‘The Polish Front and Our Tasks’ in How the Revolution Armed, Volume 3

- [5] Davies, p 63

- [6] Davies, p 93; Smele, p 153-154

- [7] Smele, p 153

- [8] Davies, p 22

- [9] Davies, p 71-73

- [10] Jackson, Robert. At War with the Bolsheviks, Tom Stacey, 1972, p 229.p 230

- [11] See Beevor, The Russian Civil War, Chapter 36; and Read, The World on Fire, p 110-111. Trotsky in May 1920 said: ‘[T]the most double-dyed demagogues and charlatans of the international yellow press will be quite unable to present to the working masses the irruption of the Polish White Guards into the Ukraine as an attack by the Bolshevik ‘oppressors’ on peaceful Poland’ How wrong he turned out to be. ‘The Polish Front: Talk with a representative of the Soviet press.’ How the Revolution Armed, Volume 3

- [12] Davies, p 89; Smele, p 320 n46

- [13] Jackson, p 229.

- [14] Davies, p 105

- [15] Davies, p 114