Review: Russia: Revolution and Civil War, 1917-1921 by Antony Beevor

Welcome to Part Two of my review of Russia: Revolution and Civil War, 1917-1921 by Antony Beevor. The previous post looked at some of the distortions and mistakes in the book. It also acknowledged some of the book’s good points. This post will set out to deconstruct the book’s overall narrative. We will expose how it shuffles around timelines and how it assumes, with zero evidence, that the events of the Civil War unfolded according to some master plan created by Lenin.

Before we begin, for the sake of balance I want to say that I don’t think the author is a liar or an idiot. My guess is that this book was produced (1) with a complacent attitude, without the author challenging the assumptions he held at the start of the project and (2) too quickly.

Back-dating famine and terror

First, let’s take a look at how the book juggles with the timeline, and what effect this has on the reader’s understanding of events.

Last week we saw how selectively Beevor quotes the writer Maxim Gorky. Likewise, he quotes Victor Serge without giving a fair indication that Serge was actually a Communist.

Beevor uses quotes from Serge to give a very bleak description of St Petersburg in January 1918 ‘after just a couple of months of Soviet power’ (Page 156). It was indeed bleak at that time. And it had been before the October Revolution too, and even before the war, working-class districts had unpaved and unlit streets. The problem is this: Beevor is quoting from Victor Serge’s novel Conquered City, and that novel is set between early 1919 and early 1920. Serge was not in Russia in January 1918. He was describing the city a year-plus later, after six to eighteen months of full-scale Civil War – not after ‘a couple of months of Soviet power.’

Beevor is back-dating the social and economic collapse of Petrograd in order to mix up cause and effect. He wants to blame economic collapse on the Revolution, not on Civil War.

We see the same pattern with the question of terror.

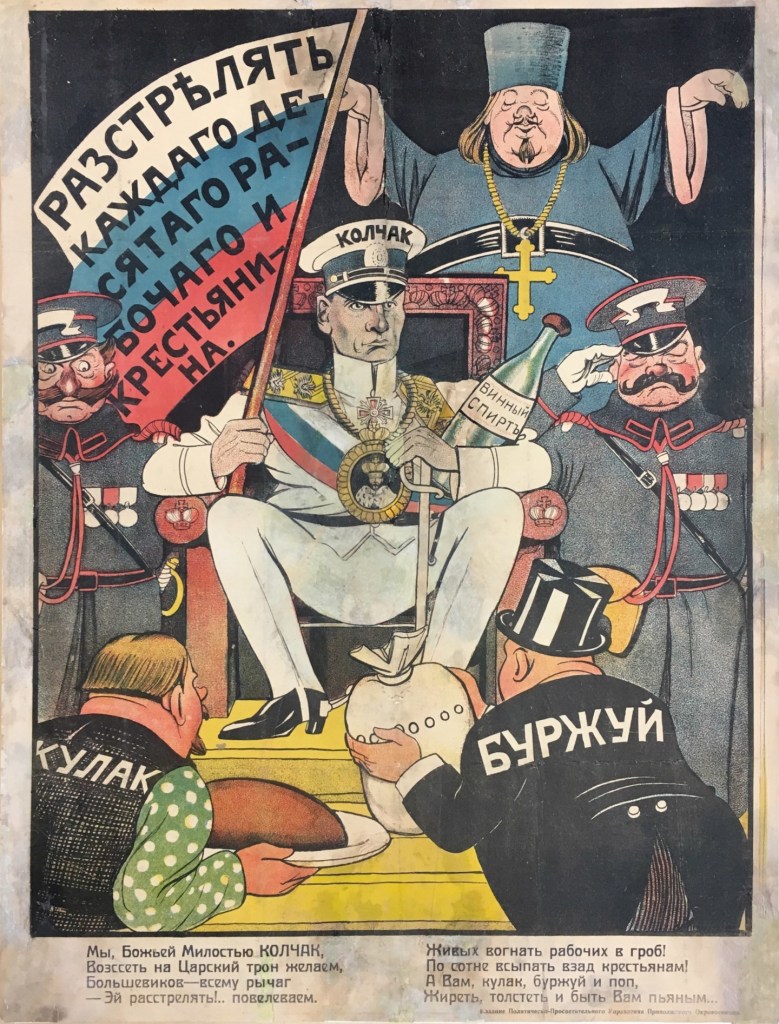

Red Terror did not begin until months into full-scale Civil War.[i] There were important outliers – the killing of officers in Kyiv (which Beevor describes[ii]) and the massacre by Russian settlers in Kokand, modern-day Uzbekistan (which he does not mention), which both occurred in February 1918. But in general, Red Terror escalated over the summer as the military and economic crisis deepened, then hit full-force at the start of September 1918.

There is state terror and then there is mob violence. Russia: Revolution and Civil War tries to blur the line between the two. Tsarist Russia was an empire of 150 million people with a threadbare state apparatus even before the Revolution,[iii] in which twelve million had been given rifles and boots and sent into a war whose traumatizing horror Beevor acknowledges. Unsurprisingly, there was mob violence and crime, and there would have been, revolution or no revolution.

He quotes an account by a bourgeois observer as evidence that the Soviets were conducting an onslaught of terror against the more affluent people: ‘They stir up the population and incite them to take part in raids and riots. This is not going to end well. There are robberies in the streets. They take people’s hats, coats and even clothes. Citizens are forced to stay at home after dark’ (Page 97-98).

Here is the note I left in my ebook:

like clearly this is a scared bourgeois conflating crime and ‘bolshevism’, not an accurate account of bolshevik activities [sic]

Did the Soviets encourage criminal gangs and robberies? No. In fact, the draconian security measures brought in by the Soviets were partly directed against such criminal activity.

Page 137: ‘Echoes of the atrocities in the south soon reached Moscow’ in early 1918 – reading this sentence I thought, ‘That’s just another way of saying you’re about to report some unconfirmed rumours you found in diaries and letters.’ Sure enough, that’s what he does, and even accepting everything at face value, you can see that this is the violence of mobs and of local self-appointed revolutionary leaders.

In the last post I mentioned Beevor’s class bias – how he tends to credit sources written by wealthy and middle-class people, and to dismiss or ignore sources written by workers. We see it at work in the example above. It is with this one-sided approach to his sources that he invents a whole new wave of Red Terror that supposedly began instantly following the Revolution. He gathers an imposing collection of anecdotes about violent acts, giving the impression that the Soviets organized it all. The number of anecdotes makes a certain impression, but no attempt is made to quantify this phenomenon.

Why does this matter? Because having back-dated the economic collapse, he is now back-dating the Red Terror. He is telling a story in which, within a few weeks of the October Revolution, Terror is in full swing and Saint Petersburg has regressed to the Stone Age.

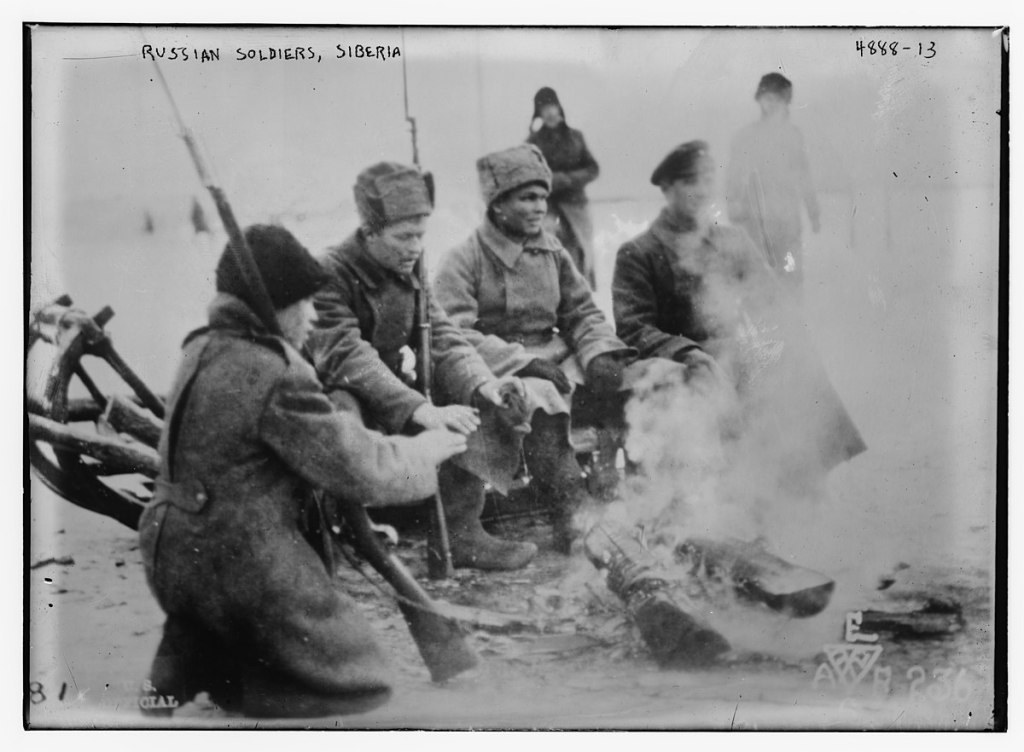

Is this really what Russia was like mere weeks after the October Revolution? No, this is what Russia was like a year after three-quarters of its territory was seized by insurgent officers, Cossack hosts and invading foreign armies.

Blind taste test

To illustrate further why this matters, I’m going to invite you to play a game, a kind of historical blind taste test. I’m going to give a brief account of two governments in two different parts of the world, decades apart. Let’s call them Govt A and Govt B. One is the Soviet Union. See if you can guess which one.

Govt A came to power in a coup in October 19__. It immediately set out on a nationwide purge of political opponents. By summer, somewhere between half a million and two million unarmed people had been killed by Govt A. Peaceful opposition parties and organisations with mass membership were not just banned but destroyed by terror, all within a few months of that October coup. Ten years later, a million peaceful oppositionists were still imprisoned in a vast network of concentration camps.[iv]

Govt B came to power in October 19__. By April of the following year Govt B had been threatened by a series of armed revolts led by military officers, but it remained a multi-party regime. In May a civil war began when most of the country’s territory was seized by insurgent forces and foreign armies. Even months into this war, congresses whose delegates were elected from field and factory still met. But eleven months after coming to power, Govt B began a campaign of terror which lasted three years and claimed somewhere between 50,000 and 280,000 lives.[v] Ten years later, the entire prison population was around 192,700.[vi]

So take your guesses. Scroll down for the answer.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Govt A is the Suharto regime in Indonesia (1965). Govt B is the Soviet regime in Russia (1917).

Suharto killed far more people in a far shorter span of time. The murder of a handful of generals by a conspiracy of junior officers was used as a pretext for massive violence against groups who had no connection to that inciting incident. On coming to power, Suharto immediately exterminated the unarmed Communist Party of Indonesia, the feminist organization Gerwani, and the trade unions. There were no exacerbating circumstances. There was no tragic upward spiral of violence. There was not the slightest element of self-defence.

It’s a very different story with the Soviet regime, which had enthusiastic popular support in the cities and at least acceptance elsewhere, and which resorted to repression only in the context of all-out war on its territory. To what extent repression was justified is a question that is not relevant to this book review. Right now all we’re doing is clarifying the context and what actually happened.

Because in essence, Beevor’s goal in the first half of Russia: Revolution and Civil War is to convince the reader that Govt B was Govt A, that Lenin was Suharto. He wishes to tell a story in which the Soviet regime, like the bloody right-wing military coups in Indonesia (1965), Chile (1973) or Spain (1936), seized power then immediately murdered the opposition. But this is simply not what happened in the Russian Revolution.

The Master Plan

A more nuanced criticism of the Bolsheviks is that they were utopian and irresponsible, that the October insurrection triggered a chain of events that forced them to adopt terror and dictatorship, and later to degenerate into Stalinism. I don’t agree with this view; I blame invasion, insurgency and blockade for the Civil War and the mass mortality which attended it.

But whichever of those two arguments you accept, Beevor’s argument stands off to one side with a demented look in its eyes. He believes that Lenin planned it all in advance – the Civil War, the confiscation of grain, terror, the suppression of opponents, one-party rule. Of course, there is absolutely no evidence that Lenin had such a plan. But for Beevor, the lack of evidence shows only that Lenin was dishonest and hid his real intentions! Childish stuff.

Just in case you think I am caricaturing Beevor’s position, here is what he says:

- Grain requisitioning was in fact an emergency response to famine; but for Beevor, it was an act of malice long premeditated in the mind of Lenin. ‘The peasants were encouraged to believe that the land would be theirs to own and work as they saw fit. There was no mention of the need for grain seizures to feed the cities or the forced collectivisation of farms.’ (Page 50) Grain seizures were not foreseen, though Fitzpatrick comments that the Bolsheviks themselves were probably more surprised by it than the peasants, from whom contending armies had seized supplies since time immemorial. And it was fair enough not to mention forced collectivisation, right? Seeing as, well, in Russia in these years, it wasn’t Communist policy and in fact it actually didn’t happen..?

- The withering of Soviet democracy was an effect of Civil War, famine and polarisation; but in this account, it was the fulfilment of a secret blueprint for a one-party state. ‘In his determination to achieve total power for the Bolsheviks, Lenin did not make the mistake of revealing what Communist society would be like. All state power and private property, he claimed, would be transferred into the hands of the Soviets – or councils of workers – as if they were to be independent bodies and not merely the puppets of the Bolshevik leadership.’ (p 50) ‘And because he knew very well that his plan of complete state ownership was not popular, he simply paid lip service to the idea of handing the land over to the peasants and factories to the workers.’ (Page 62) The casual reader, for whom this is the first thing they ever read on the Russian Revolution, would not suspect that such documents as ‘The State and Revolution’ or ‘The impending catastrophe and how to combat it’ ever existed. They would assume that what Beevor is saying is based on some document or other written by Lenin where he reveals his secret plans. There is no such document. The casual reader (and maybe even Antony Beevor) would be surprised to learn that four Soviet congresses met in 1918 and that by the end of the war there were still large numbers of factories democratically run by their workers.

- The other elements of the master plan, the Cheka and Lenin’s supposed plan to deliberately start a Civil war, are dealt with here.

We can say categorically that there is no evidence that such a master plan ever existed. If you look at what the revolutionaries actually wrote, said and did, it is clear that they favoured a gradual socialisation of the economy, the sharing-out of land rather than collectivisation (collectivisation was to be a gradual and voluntary process lasting decades), and multi-party democracy in the Soviets.

Later, some Communists made a virtue of necessity. But still, more than traces of the original plan are visible down through the years. In early 1919 the Soviets were willing to surrender most of the territory of Russia to the Whites, just to end the war – hardly consistent with the supposed master plan. Right after the abrupt ending of Beevor’s narrative, millions were demobilised from the Red Army, the Cheka was radically downsized and curtailed, and the New Economic Policy (NEP), which favoured the peasants, was brought in.[vii]

This point applies to the back-dating which I described earlier. Why does it matter if a writer shuffles things around by a few months? Isn’t this a justified simplification for the sake of clarity? In his point of view it probably is. But months, weeks and even days can matter a great deal. Torture, invasions and the USA Patriot Act were not brought in before September 11th 2001. Likewise events before May 1918 and after May 1918 must be judged by different criteria. For example, a radical economic plan from the Left Communists was actually rejected by the Party in March 1918. But in the context of the extreme military and economic emergency that very quickly emerged, most aspects of it were adopted out of necessity and became known as ‘war communism.’

I don’t accept Beevor’s narrative. I believe that the forced seizure of grain was an emergency response to famine, not an act of senseless vandalism born under the malicious cranium of Lenin.

The reasonable debate you can have here is whether they were effectice or fair reaponses. But because Beevor has set out to tell a certain story, we never get that far.

The crises which led to terror, requisitioning, dictatorship etc are treated as if they were results of terror, requisitioning, dictatorship etc. Beevor leaves the uninformed reader with the impression that the officers and Cossacks rose up in arms because they were outraged by a situation which did not arise until months later – and which arose due to their insurrection! In this way, Russia makes an absolute mess of cause and effect.

Blame on both sides of the equation

In passing, note how no opportunity is missed to condemn the Reds. The ‘Bolsheviks’ are blamed for supposedly failing to cooperate with others, but they are also blamed whenever someone with whom they cooperate does something bad (Muraviev); they are blamed for crime, and also for the draconian security measures which were partly directed against crime; they are blamed for the mistreatment of civilians by the Red Guards, and also for the harsh discipline which put an end to this behaviour. Further explanation is required, surely, when blame is placed on both sides of the see-saw.

Conclusion

This is a vigorous but crude book because, for all its grisly detail, it dispenses with nuance. The author has decided to convince us that Lenin is like Suharto, even like Hitler (more on that next post!). He’s not the first but it’s a bold move. This all-out ‘take-no-prisoners’ approach gives the writing some vigour, but it goes against the grain of reality, compelling the author to back-date key developments and, furthermore, to insist that these developments were the fulfilment of a secret master plan. What emerges is something compelling but not convincing.

A more skilful demonisation of the Reds would emphasise that ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions,’ etc, etc, would use the bright colours as well as the dark, would not neglect to use the elements of tragedy which so obviously present themselves. Most accounts, from every side of the political spectrum, do this to some extent. But Beevor has taken a gamble, and gone for something bolder. He has fallen short, because reality does not correspond to the story he is trying to tell.

So Russia: Revolution and Civil War lands with some force, but it does not stick. Even those who are stunned into an uncritical acceptance of Beevor’s narrative will be able to see clear daylight through the gaps in the narrative, and may later reconsider, especially if they end up reading a few other bits and pieces on the same topic.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

My previous post on Russia: Revolution and Civil War

[i] This is not just my contention. Here is just one example which I have to hand as I write, from an account not sympathetic to the Soviets: Silverlight, The Victors’ Dilemma, Page 15: ‘real oppression did not start until the Terror, several months later.’

[ii] This massacre of officers cannot be justified with reference to existential threats. Estimates of the death toll range from the low hundreds to the thousands. But important parts of the context are missing from Beevor’s account: the suppression of the Kyiv Arsenal revolt by the Rada, the killing of prisoners by the Rada, and the fact that the Red Guard force which carried out the massacre was a notably undisciplined one led by the adventurer Muraviev, an officer who had recently joined the SRs. Needless to say, the broader context (his account of the conflict between Rada and Soviet) is one-sided.

[iii] ‘in 1900 an individual constable in the countryside, assisted by a few low-ranking officers, might find himself responsible for up to 4,700 square kilometres and anywhere between 50,000 and 100,000 inhabitants.’ Smith, Russia in Revolution (p. 19)

[iv] See The Jakarta Method by VIncent Bevins, PublicAffairs, 2020

[v] The lower figure comes from Faulkner, ‘The Revolution Besieged’ in A People’s History of the Russian Revolution and the higher figure from Smith, Russia in Revolution: ‘One scholar estimates that between October 1917 and February 1922, 280,000 were killed either by the Cheka or the Internal Security Troops, about half of them in the course of operations to suppress peasant uprisings.’ (p. 199)

[vi] Peter H Solomon Jr, Soviet Penal Policy, 1917-1934: A Reinterpretation

[vii] None of this is secret lore. On the land question, see the collection The Land Question and the Fight for Freedom. On the rejection of the Left Communists’ proto-war communist plans, see Year One of the Russian Revolution by (none other than) Victor Serge. On the Soviets’ peace plan, see any history of the Civil War. On the downsizing of the Cheka, see Smith: ‘At the end of 1921 there were 90,000 employees on the official payroll of the Cheka, but by end of 1923 only 32,152 worked in OGPU.’ (Russia in Revolution, p. 296).