At 18 I visited China during an ambitious bit of backpacking. One day a Chinese woman working in a hostel held up a banknote with Mao’s likeness on it and assured my companions that if you placed your finger on his chest you could feel his heart beating. My friends reported this to me and I reacted with scorn. You see, I had read Mao: The Unknown Story by Jung Chang and John Halliday (not even all of it), and I knew everything. I could not explain by what mechanism Mao had managed personally to kill seventy million people, but I did not doubt that he had pulled it off, and that anyone who admired him for any reason was deluded, maybe even dangerous.

In fact I didn’t know all that much and I still don’t. But in the intervening years I’ve come to learn bits and pieces more.

We didn’t learn anything at all about China in school but we did learn about the Russian and French revolutions. The focus was on political leaders and the struggles between them. In real life, the social changes experienced by the masses were the central questions in the revolution, but they were an afterthought in the education system and on the history shelves of bookshops.

This western discourse might stop only long enough to note that the ‘ordinary person’ suffered before the revolution but, it is asserted, suffered worse after. So I knew about the nonsense with the sparrows and the backyard pig iron forges long before I knew about the greatest social change which the French, Russian and Chinese revolutions had in common: the land revolution.

Probably the most important development in global history in the Twentieth Century was the transfer of land from a small class of landlords to the majority, to the peasant farming population. This was not communism or socialism, just democracy. But in the last century, it mostly happened in communist-ruled countries such as the People’s Republic of China, although it was and is proverbially not a democratic state in the sense of electing the leaders, the right to free political activity, etc.

They didn’t teach me about this in school, or in the history book reviews in the Sunday papers, or in Mao: The Unknown Story. I’ve picked it up elsewhere, most of all in a book I’m currently reading called Fanshen by William Hinton.

About the book

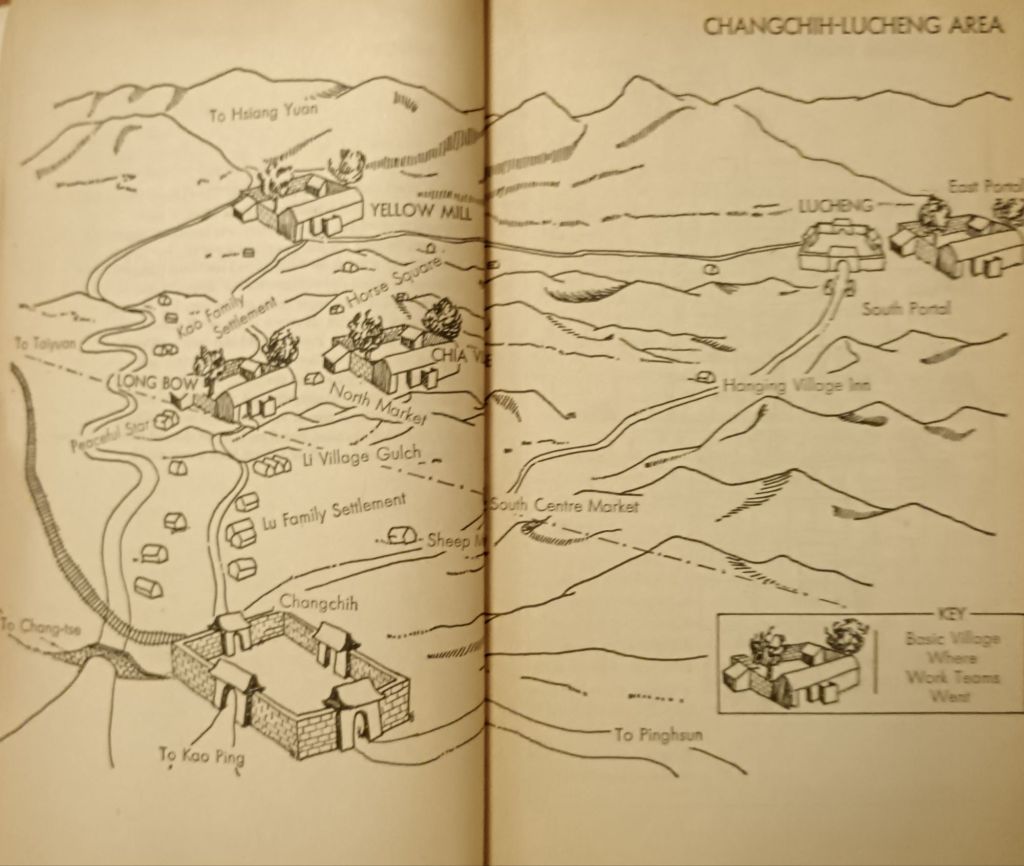

William Hinton is from the United States and he was in China in the late 1940s. He went to a village called Zhangzhuangcun[i] in Shanxi Province where, with the help of a translator, he took down a massive heap of notes recording the experiences of local peasants during the prior few years of war and revolution.

Hinton came back to the United States, whose government confiscated his notes and kept them under lock and key for the better part of two decades. They figured that reading about the lived experiences of Chinese farmers would be extremely dangerous for the health and safety of US citizens. Hinton finally got his notes back and wrote and published Fanshen in the mid-1960s.[ii]

I’ve always been a bit confused as to what a ‘village’ is supposed to be, and Fanshen has added to my confusion, because Zhangzhuangcun was not an expanse of fields and scattered houses, or a built-up crossroads, but a dense collection of buildings, in and around which lived roughly a thousand people, surrounded by farmland. Early on we get a beautiful description of the place before we zoom in on the absolute misery in which so many of its people lived.

A handful of families around the village own most of the land and keep the rest in debt slavery and servitude. These landlords bring in rents and harvests, build big houses, buy more land, lend at extortionate rates, swindle their illiterate tenants and debtors, and buy the children of people they have reduced to absolute desperation. What do the landlords do with the proceeds of all this exploitation? Send their children to college; buy more land, make more loans; distil alcohol; buy silver and bury it in the ground.

But the social life of the village is complex and has many layers and moving parts. This is a big book because Hinton doesn’t try to con us with an overly-simple story. For example, the way these landlords live, I wouldn’t call it luxury. They lived on dirt floors. What they had was power over others.

Soldiers were occasionally present in town (harassing women, drinking) but mostly the landlords kept control through informal means. Religion and the supernatural feature heavily. There is the Confucian society, the Buddhist temple and the Catholic church. Each one is employed as a racket by the ruling layer in the village. But they also have plenty of sincere believers including many who take part in the revolution. The Catholics themselves enlist to challenge the parish priest.

There is also, unrelated to landlordism but symbolic of it, a clay statue who must be appeased with sacrifices so that he will not inflict an illness on the villagers. I think it’s scrofula. During the revolution, some folks pluck up the courage to overthrow and destroy this deity. When no illness comes to afflict the iconoclasts, the villagers learn that the god has no power after all.

Other forces in the mix are bandits, the Nationalists, the Communists, and the Japanese and their local puppets. Hinton shows what each of these forces meant in the context of ordinary people’s lives and paints a picture that feels rich and alive. From the day the Japanese and the puppets are driven from the village, the land revolution proceeds: first as a reprisal against collaborators, then as a campaign against the most abusive of the landlords, then against the landlords and rich peasants generally. The picture is not rose-tinted: Hinton tells us how several landlords or their family members or allies were killed or tortured, sometimes in the pursuit of buried treasure that did not exist.

Land Revolution

The book is fundamentally about land revolution. We’re talking about the redistribution of the property of around 5 percent for the benefit of the rest. Objections to wealth redistribution are well-known: this would only be an ‘equal sharing-out of misery’; socialism fails when you ‘run out of other people’s money’; and people will have ‘no incentive to work.’

Having debated these things so many times it’s refreshing to see them answered on the comprehensible and relatable scale of one village.

‘Equal sharing-out of misery’

It turns out that, yes, sharing out the luxuries and household goods of the rich does benefit the community as a whole. Witness the memorable scene in Fanshen in which a strange kind of market takes place. All the confiscated goods of the landlords are laid out in the temple square, and the villagers come in groups, starting with the poorest, each to pick out one item.

In the months and years of the revolution, a lot of other things get shared out or made collective property: the buried silver; the landlords’ open or covert control over religious and public institutions.

But the most important part is the sharing-out of the land, livestock, implements – the means of creating wealth. This is the real game-changer. This is fanshen – a phrase which Hinton explains as meaning something like ‘to turn over.’ For the Chinese farmer in the 1940s, eking out a miserable precarious existence through ceaseless toil while enriching a landlord, fanshen meant taking over a proportionate share of the landlord’s property and beginning to live with dignity and independence. In the background is the China-wide process of fanshen. This entity called the Border Region government will develop into the People’s Republic of China; the Eighth Route Army, which is idolised by poor peasants, will become the People’s Liberation Army.

‘Running out of other people’s money’

The windfalls from sharing out the landlords’ property were so intoxicating that the local activists tried to cast the net wider and ever-wider, usually in direct defiance of orders from the communist-led government, shaking down more and more of their well-to-do neighbours. This led to some violent abuses and excesses. The diminishing returns were apparent. In this sense, there’s a kernel of truth in the idea that socialism (or in this case democracy) works until you ‘run out of other people’s money.’ Of course, the villagers were reclaiming rent extorted and conned from them so it was their own wealth – but it was indeed finite, it could ‘run out.’ This was a secondary problem. The activists simply accepted that redistribution was as complete as it was ever going to be, and corrected their course.

‘No incentive to work’

Wealth came from other sources. There was a new and impressive movement of cooperatives. More importantly,contrary to the idea that sharing destroys the ‘incentive to work,’ the farmers now had more land and implements and were freed from debts and rents, so they were willing and able to work harder and produce more.

Those whose wealth had been taken from them did indeed lose an incentive to work, and this was an economic problem, but again, it was one of secondary importance. For the majority of people, obviously, the land revolution meant a tremendous new incentive to work.

Conclusion

All these questions are played out in Fanshen in a compelling drama with a huge cast of characters. It throws a new light on other things I knew about. The ritual denunciations during the Cultural Revolution were self-conscious re-enactments by students of the revolution the previous generation made. But it’s much more sympathetic to read about a bunch of peasants finally ganging up on their landlord and denouncing him for starving their children than it is to read about a bunch of students, twenty years later, doing the same thing to a professor because he’s allegedly a ‘capitalist roader.’ The thing is, I was acquainted with the grotesque student re-enactment many years before I read about the dramatic village meetings they were trying to emulate. Completing this circle adds pathos to both.

I’m about half-way through the book and may follow this up with further notes as it enlightens me further.

I’m still not a fan of Mao Zedong for a variety of reasons to do with his disinterest in democratic rights, his treatment of his political rivals from the 1930s on and his calamitous mistakes with regard to the ‘Great Leap Forward’ and the later Cultural Revolution. So I’m not here to make you Mao-pilled. But for people in North America or Europe to understand and respect people from China, it’s important to understand the reasons why Mao, the PLA and the CCP have been held in such high regard for so long.

Going back to that woman in the hostel who said you could feel Chairman Mao’s heart beating in the paper of a banknote. I don’t know, but maybe her grandparents went through this fanshen, a process they associated, reasonably, with the man whose face was on that banknote. This doesn’t mean I can’t criticise him but it does mean I should try to understand where she was coming from. Maybe lots of Chinese people would also find that kind of thing very embarrassing. But my scorn was not authentically my own.

[i] In an uncharacteristic bit of pandering to the western reader, he takes the liberty of calling the village ‘Long Bow’ though he admits this is not a translation of its name. So why call it that..?

[ii] The edition I have is from the 1990s, withdrawn library stock that I found in a second-hand bookshop.