During the Russian Civil War the Soviet Republic was a besieged fortress. What’s less well-known is that it had an outpost thousands of kilometres away in Central Asia, centred on the city of Toshkent (Tashkent) in modern-day Uzbekistan. The Toshkent Soviet was itself a Red island surrounded by enemies, and its struggle for survival, like the broader Civil War, was a drama rich in ironies and sudden reversals, sometimes horrifying, sometimes inspiring. It is also a historical curiosity: a revolutionary workers’ republic in the heart of Asia, where Muslim farmers and nomads outnumbered the Russians ten to one. It demands attention as a kind of scientific ‘control’ for the Soviet experiment; there was another Soviet Union, separated from the main one for a long time, and unlike the Soviets of Hungary and Bavaria, it survived.

‘For nearly two years,’ wrote the Bolshevik Broido, ‘Turkestan was left to itself. For nearly two years not only no Red Army help came from the centre in Moscow but there were practically no relations at all.’ (Carr, 336) What’s this Turkestan? It was their name at the time for, broadly speaking, the lands we now call Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. A more recent historian writes: ‘The survival of Soviet power in Turkestan is another testament to the popularity of the Soviet revolution and the weakness of other forces.’ (Mawdsley, 328)

Ultimately the Revolution would bring massive changes to Central Asia, which included:

- Land redistribution at the expense of the feudal rulers;

- The expulsion of vast numbers of racist and violent Russian settlers;

- The birth of the states which would become Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, the Kyrgyz Republic and Kazakhstan;

- The enormous expansion of schools, universities and libraries.

(Dilip Hiro, Inside Central Asia, Overlook Duckworth, 2009, 2011, p 31, 33)

But when you read on about the massive forces ranged against it – from White Guards, Muslim rebellions and British intervention to the racist attitudes of many local Soviet leaders toward the Muslim majority – you will wonder how this revolution survived for a single year.

Class War and Holy War: Revolution Under Siege in Central Asia, 1918-1920 will be a three- or four-part miniseries branching off from my series Revolution Under Siege.

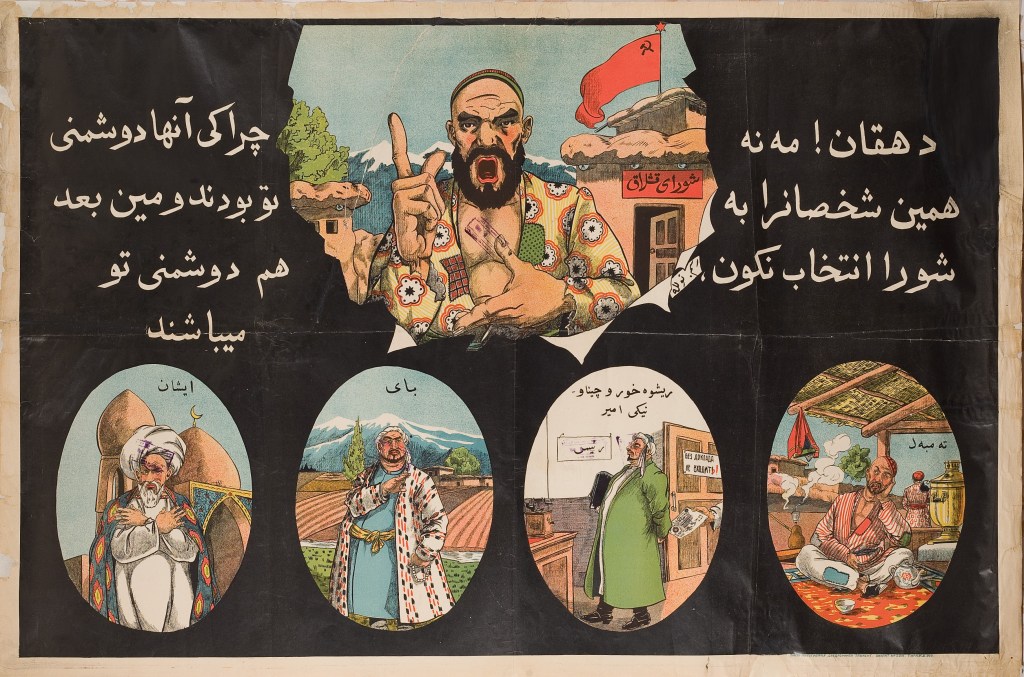

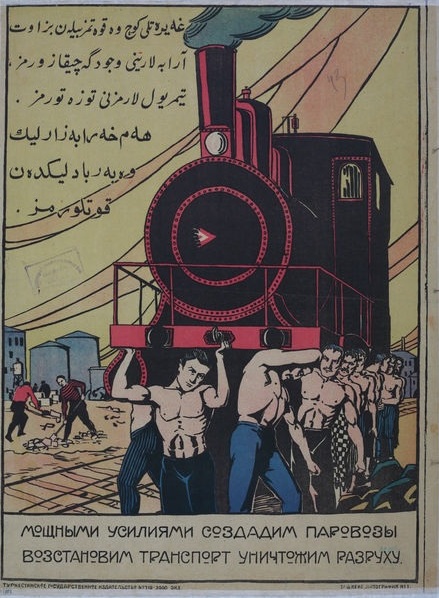

(I’m grateful to this article on an exhibition titled ‘Posters of the Soviet East’ by the Mardjani Foundation for many of the images I have used in this series, including the cover image for this post.)

How people lived

My readers are mostly from English-speaking countries, where ignorance reigns about Central Asia. The only reference point common to most of my readers is a mockumentary starring a guy from London posing as a representative of the Kazakh government, who says outrageous things in a funny accent (‘Very nice, how much?’ – ‘You are retarded?’ etc), his Polish-Yiddish ‘hello’ standing in for Kazakh.

Not to get up on my high horse. All I know about Central Asia is what I read in a handful of books over the last few months. But learning proceeds by successive approximations. I’ll be guilty of mistakes and omissions, but anything is better than nothing. For knowledge – obviously not for laughs – I reckon I can probably improve on Borat.

To visualise these peoole, first let’s exorcise from our minds images of Sacha Baron-Cohen’s jaunt around an unsuspecting Romanian village. The best place to start is by sketching how the people lived in this region around the time of the Revolution.

Imagine a house with a courtyard surrounded by a wall high enough to block you from seeing in from outside. In the house lives a father with a white beard who wears a turban and a long black jacket. Under his patriarchal authority live his sons and their wives and children, each in their own room which opens on the garden and courtyard. None of them can read.

(Dilip Hiro, Inside Central Asia, Overlook Duckworth, 2009, 2016, 20-30)

If they are poor, there is no glass in the windows, and the children and even babies go naked while their only set of clothes is being washed – even in the snows of winter. The ubiquitous item of clothing is the khalat, a loose gown.

The house is part of a community built near an oasis or a river in a landscape of ‘sparsely populated and starkly contrasting reaches of steppe and mountains.’ (Smele 228) They make a living through farming, commerce and handicrafts. The white-bearded old men of the locality are in charge. They answer to beks, landlords who administer justice. The Muslim clerics are another source of authority, divided into two schools: the conservative Qadim and the modernising Jadid. There are 8,000 Islamic schools in the region but only 300 national schools.

(Hiro, 50. Rob Jones, ‘How the Bolsheviks Treated the National Question,’ from internationalsocialist.net, 31 Mar 2020, https://internationalsocialist.net/en/2020/03/the-russian-revolution).

The bek might sentence a criminal to hanging, shooting or beating or to the public humiliation of face-blackening. Above the bek there might be a khan or emir, who answers in turn to a white Orthodox Christian in distant St Petersburg, the Tsar of Russia, whose forces conquered the region only within the last two or three generations.

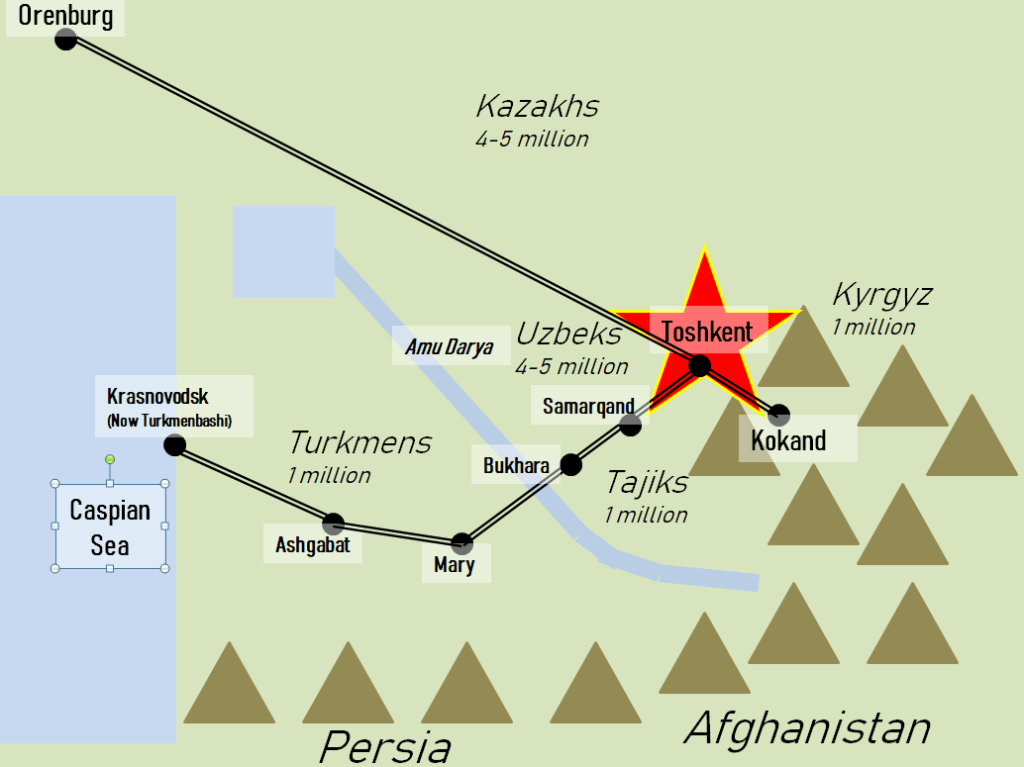

These are the settled people: 4 million Uzbeks, who spoke a Turkic language, and their close neighbours, the million Persian-speaking Tajiks. The Fergana Valley lies between the two, an area rich in cotton which, under the Tsar, has been intensively developed and commercialised.

Then there are the nomads. Imagine another house, this one made of felt and furs, which the women of the family can assemble or take down in a few hours. The Kazakhs, whose name means ‘Wanderer,’ are the most numerous, 4.5 million of them divided into three ‘hordes’ between the Caspian Sea and the border of China. The most stubbornly nomadic of the Kazakhs are distinct as the ‘Forty Tribes,’ the million Kyrgyz who live on the eastern plateaux, brave draft-dodgers and rebels. By the Caspian Sea live several Turkmen tribal groups, nomads whose numbers add up to another million. The nomads live by nomadic stock-breeding, along with marginal agriculture and the caravan trade.

(Smith, SE, Russia in Revolution, 57)

These 11 or 12 million scattered Muslims, who mostly identify not with any national project but with the local clan, village or oasis, are held by the centrifugal force of the 78 million Russians of the Empire, 3 million of whom live in Central Asia. (Mawdsley, 31, 38)

Silk roads and iron roads

This region was once the nexus of the world, ‘full of the traditions and monuments of an ancient civilisation’ along the legendary trade routes known as the Silk Roads. (Carr, 334) Around 1000CE it used to be said that the sun doesn’t shine on Bukhara – Bukhara shines on the sun. In 1918 it was still considered the holiest city in Central Asia, difficult of access to non-Muslims. Mary (Merv) was ‘Queen of the World’ until the Mongols sacked it. Samarqand was famous for its beautiful turquoise domes, and as the one-time capital of the vast empire of Timur Bek, known and feared in Europe as Tamerlane. There were also sites associated with a recent history of resistance, such as Geok Tepe, where the Turkmens made their heroic last stand against the Tsar in 1881.

(Teague-Jones, Reginald, The Spy Who Disappeared, Gollancz, 1990, 1991, 55)

During the time of our story all these peoples and cities are lumped together in three vague regions: Kazakhstan, ‘Trans-Caspia’ (modern-day Turkmenistan) and ‘Turkestan’ (Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to us). Got that? Turkestan and Turkmenistan are not the same place. Most of these groups were intermingled throughout the region, rather than having their own exclusive territories. Also, the Russians mistakenly called the Kazakhs ‘Kyrgyz’ and the Kyrgyz ‘Kara-Kyrgyz’… And then there’s the Kalmyks…

But I’ll try to stay on course. Just remember that these different communities and identities are no more and no less complex than, say, those of Europe – just less familiar to the English-speaking reader.

Crossing the deserts and mountains and valleys are two railway lines and some telegraph wires. They are the slender threads by which Imperial Russia sends in settlers and extracts cotton. By 1917 there are many Russians in Central Asia, concentrated in their cities, depending on the metal threads, or else spread out in farming settlements, clashing with the natives over land and water rights. Cotton production has boomed since Tsarist rule began in the 1860s, machine-compressed bales of cotton exported by the thousand over the railways, north-west to Orenburg, or west to the Caspian Sea. But the link to a global capitalist market is a mixed blessing: now and then the market crashes with devastating results for local people: ‘a bumper crop in Louisiana could spell disaster for Fergana.’ (Smele, 18)

The iron roads have transformed Toshkent, an ancient site whose name means ‘city of stones.’ 2,000 Tsarist soldiers crossed the river one night in 1865 and seized the town; since then the Europeans have built a grid-patterned ‘new town,’ wide boulevards lined with silver poplars, turtle-doves on the rooftops. Hundreds of thousands of Russians migrated there to serve as clerks, technicians, skilled and semi-skilled workers, not to mention soldiers. There they enjoy electricity, piped water, trams, phones, cinemas, and a commercial district. It is a city of 500,000 people. Rents are high. Sedentary Uzbeks work the less prestigious jobs in cotton processing. Like in another region associated with cotton, the South of the United States, the front seats on the trams are reserved for white people.

(Hopkirk, Setting the East Ablaze, Oxford Univeristy Press, 1984, 2001, 21. Hiro, 27)

This is a diverse and colourful region. One day at a train station in 1918 in modern-day Turkmenistan, ‘Russian peasants in red shirts, Persians, Cossacks and Red soldiers, Sart traders and Bokhariots, Turkmans in their gigantic papakhas [hats]… pretty young girls and women in the latest Paris summer fashions’ could be observed clamouring at a counter for tea and black bread. (Teague-Jones, 57)

World War One brings first difficulties and then devastation. The price of cotton plummets, those of consumer goods rise. The Tsarist government requisitions horses. Early on, food is more plentiful here than in other parts of the empire. Captives from the armies of Germany and (far more so) Austria are sent here in their thousands – 155,000 by the start of 1917. (Mawdsley, 328) There are eight squalid prisoner-of-war camps in the vicinity of Toshkent alone. Food becomes scarce later in the war, and the captives begin to die in terrible numbers.

In 1916 the government tries to conscript the peoples of Central Asia for combat and forced labour. The Kyrgyz and Kazakh nomads start a guerrilla war in response, backed up by settled Uzbeks protesting in Toshkent and Kokand. The Tsar responds with a fury that will not be matched until the period of forced collectivisation under Stalin. Three years later an eyewitness will record that once-busy villages are still absolutely deserted. At least 88,000 are killed in the crackdown led by General Ivanov-Rinov, and twenty percent of the region’s population flee into China. (Smele, 20-21)

Revolution

So the Muslims of the Russian empire anticipated the Revolution with their failed rising. They were also active participants in the 1917 Revolution – though the most active elements were not those of Central Asia but their distant cousins, the Muslim minorities who lived around the Volga and the Urals. There were great Muslim congresses in 1917, from which emerged three political tendencies:

- The Jadids – modernising clerics who called for ‘land to the landless’ and to ‘expropriate the landlords and capitalists.’ These were stronger on the Volga than in Central Asia.

- The Qadims – conservative clerics, who called for Islamic law for Turkestan. Their organisation, the Council of Ulema, was the only real political party among the Central Asian Muslims.

- The Alash-Orda – these Kazakh and Kyrgyz nomads demanded the return of land from Slavic settlers.

It is interesting that there was no prominent demand for independence or any obvious signs of Pan-Turkism.

(Hiro, 31-3)

When the October Revolution took place, it was obvious even from the distant vantage point of revolutionary Petrograd that there would be profound consequences for Central Asia. After the 650 delegates of the All-Russian Congress of Soviets seized power they immediately ‘resolved to decolonise the non-Russian areas of the Tsarist Empire.’ (Hiro, 33)

A voice from Central Asia, albeit a Russian one, was heard at the congress. The Menshevik-led railway union declared a strike against the new Soviet power, but it was clear that they did not speak for all railway workers. ‘“The whole mass of the railroad workers of our district,” said the delegate from Tashkent, “have expressed themselves in favour of the transfer of power to the soviets.”’ This decision of the Toshkent rail workers in favour of Soviet power was to have historic consequences.

(Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, Vol. III, Ch 47, ‘The Congress of the Soviet Dictatorship,’ Gollancz, 1933, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/hrr/ch47.htm)

This was the age of the “white man’s burden,” when moderate British politicians spoke approvingly of “maintaining White Supremacy” in India; when a racial equality clause was rejected for inclusion in the Versailles Treaty; when almost all of Africa was under the control of a handful of European empires.

In this context, to declare support for self-determination, up to and including full independence, was a revolutionary act. Lenin, Trotsky and the Bolshevik party as a whole showed a bold and liberatory approach in this respect.

In Finland, a few hours by boat from where the delegates met, the resolution on self-determination was given effect within days. Six months later, however, the Finnish socialists had been killed in their tens of thousands by a triumphant White Finnish army. The episode raised uncomfortable questions about the Soviets’ support for national minority rights and self-determination. The Finland events illustrated the tension between the principle of self-determination and the cruel realpolitik of a world still dominated by imperial and bourgeois forces. Nationality and religion could be employed as flags of convenience for the threatened ruling classes to play divide and rule and to rally a constituency against the demands of the poor and the working class. The equal and opposite danger was that the Revolution would be used as an excuse to re-impose the old centralised, top-down and racist order. These were the rock and the hard place between which the Revolution would have to navigate. In this delicate task the inexperienced revolutionaries at the helm in Toshkent would fail utterly.

National Chauvinism

The Toshkent Soviet had zero Muslims in its highest tiers of authority. In fact, Muslims were openly excluded from such positions in a resolution of the Toshkent Soviet of December 2nd 1917. (Carr, 336)

How much of this is sociology bleeding into nationality? The difference between Russians and Muslims was in a sense just the local version of the difference between workers and peasants. Relations between the cities and the villages were often extremely tense during the Civil War. Was this not just the familiar urban-rural divide, with different trappings?

But the national-religious division in Central Asia was much deeper and more violent. The Russian worker was two, one or zero generations removed from the village, spoke the same language and practised the same religion as his rural cousins. The Russian settler in Central Asia was a stranger whose impositions were backed up by the force of an empire. This informed the ‘pronounced chauvinism of local Bolsheviks.’ (Smele 232) Almost all of these Bolsheviks, by the way, were recent recruits to the party; there were few Social Democrats in Central Asia pre-1917, and they had not split into Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. (Carr, 337) Hence they lacked any grounding in basic party policy on nationalities.

Throw in three years of total war and a year of revolution, and it was all-too-easy for some Russian workers to default to chauvinism and racist violence.

The indisputable example of this is the Kokand massacre. In all the history of terror in the Civil War, there are few parallels with the events in Kokand in February 1918. But before we deal with that event, we’d better explain how the October Revolution took place in Central Asia.

October in Toshkent

China Miéville has a novel called The City & The City in which two states occupy the same physical space, each wilfully ignoring the other, the inhabitants carefully ‘un-seeing’ citizens of the other city. Central Asia in the revolutionary period was a bit like that. Two peoples living parallel lives went through parallel revolutions. Large numbers from the ten-to-one Muslim majority rose up in a guerrilla struggle in 1916, as we have seen. The Russian workers in Central Asia, meanwhile, were thousands of kilometres from Petrograd or Moscow, but those railway lines and telegraph wires were like neural pathways, rapidly transmitting stimuli and responses. There developed a Toshkent Soviet and a Toshkent Red Guard 2,500-strong. Not only did it keep step with the Soviets of European Russia, it seized power for 5-6 days a month before the October Revolution with the support of a Siberian regiment. (Hiro, 34) Here the Social Revolutionaries and not the Bolsheviks held a majority in the Soviet. The uprising was suppressed by Kerensky’s Provisional Government with military force. But this provoked a backlash: forty unions participated in a general strike against the imposition of martial law.

(Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, Vol. II, Ch 37, ‘The Last Coalition,’ Gollancz, 1933, p 344. https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/hrr/ch37.htm)

Just seven days after the storming of the Winter Palace in distant Petrograd the Toshkent Soviet took power again. This time Soviet power was here to stay. The new commissars included as many SRs as Bolsheviks. Sometimes it becomes quite obvious that revolutionary politics is sociology with guns: the key force behind the Toshkent Soviet was the working class of the city, especially the railway workers. The president was a Bolshevik, F.I. Kolesov, a railway worker like most of his fellow commissars.

The Turkestan Bolsheviks were weak. They only held their first conference as late as June 1918, at which a grand total of 40 delegates were present. Nationally, the Bolshevik-Left SR coalition broke up in March 1918; in Toshkent the coalition continued into 1919.

But the parallel revolutions were set to collide.

In September a Muslim congress had taken place in Toshkent, producing a demand for autonomy and Islamic law in Central Asia. (Hiro, 33) On 26 December a mass demonstration of Muslims took place in Toshkent – a crowd of hundreds of thousands filled the streets with people, horses and religious banners. The marchers wore white turbans, colourful silk coats and high leather boots. This demonstration descended into bloodshed after demonstrators attacked the town prison and freed the prisoners. Next they tried to seize the arsenal, the jail and the citadel. The Soviet intervened with machine-guns. (Hopkirk, 23)

By the start of 1918, two rival governments had arisen: the Toshkent Soviet and the Kokand Autonomous Government. Kokand was a mud-walled caravan city, a few stops eastward on the railway. The Kokand government was an alliance of modernising Jadids and conservative Qadims, (Smith, 192), a continuation of the Muslim conference of September, which had gathered 197 delegates from Syr Darya, Bukhara, Samarqand and Fergana. Its programme, according to Carr (336) included the maintenance of private property, religious law and the seclusion of women. ‘It received support from bourgeois Russians hostile to the Bolsheviks’ but in general the national-religious question was paramount.

The Kokand Massacre

Through most of January the two sides tried to negotiate, without success.

The Kokand Citadel was still occupied by revolutionary Russian soldiers. The forces of the Kokand Autonomy made a failed attack on the Citadel in early February, and the soldiers inside appealed to Toshkent for aid. An army set out at once by rail, a haphazardly-gathered force: Russian soldiers and Red Guards, and former POWs from Central Europe, and mixed in with these, mercenary elements out for loot. The army crossed the red-tinted mountains by the 2,000-metre-high Kamchik Pass and descended into the Fergana Valley. This army laid siege to the walled Old City of Kokand. One week later, reinforcements arrived from Orenburg; these forces had just defeated the Cossack Ataman Dutov and his Muslim allies, the Alash-Orda.

After another week the city walls were breached, and the carnage began. For three days the forces of the Toshkent Soviet looted and murdered in the city. Homes, mosques and caravanserais were burned or desecrated. Somewhere between 5,000 and 14,000 civilians were murdered in this rampage, apparently ‘almost 60 per cent of the population.’

(Hiro, 36, Hopkirk, 25, Smith, 192)

Along with the roughly concurrent events in Kyiv, the massacre in Kokand was an important early outlier of violence from the Red side. What the Kokand and Kyiv violence had in common was that they were carried out by forces at a remove from the Bolshevik-led government; the Kyiv forces were led by the adventurer Muraviev who later revolted against the Soviets, while the Toshkent forces likewise had a weak Bolshevik presence and had little contact with Moscow. More damningly, both early outliers of terror were carried out in non-Russian areas of the former Tsarist Empire, which points to racist motivations.

The similarities end there; in Kyiv, the Red forces targeted mostly officers and the death toll may have been in the hundreds and not the thousands, while in Kokand, the terror was a sack and massacre worthy of the Crusades. A Danish officer recorded that every one of the participants in the medieval-esque conquest of Kokand came back to Toshkent rich. ‘Elsewhere in the Fergana Valley armed Russian settlers terrorized the natives,’ adds Smith.

That was the end of the Kokand government. But the Soviet project would pay a heavy price for the brutal actions of the Toshkent commissars. The massacre was a key event in triggering the Basmachi rebellion, a guerrilla war which would, as we will see in future posts, torment the region for years to come. 1918 saw 4,000 Muslim kurbashi, ‘fighters,’ begin to wage guerrilla war in the Fergana Valley.

‘Barbaric deeds were performed by both sides’ in the Civil War in Central Asia, writes Hopkirk (4). ‘Some of those carried out in the name of Bolshevism would have dismayed Lenin.’ Alarmed by events in Turkestan, which they probably only had partial knowledge of, Moscow authorities sent P. A. Kobozev to urge a change of course.

The Toshkent Soviet still had other opponents in neighbouring towns. Under the Tsar autonomous kings had ruled in parts of Turkestan, ‘the already enervated and last remnants of the Mongols’ Golden Horde’ (Smele, 232) and these emirs and khans fought hard to hold onto their lands and titles. The Reds took Samarqand, though the troops there soon mutinied; a trainload of Austro-Hungarians put down the mutiny after a brief clash.

Bokhara proved a tougher nut to crack. President Kolesov showed up outside its gates one day with a large force of soldiers, some artillery, and an ultimatum. He sent a delegation into the city demanding the Emir’s surrender. The Reds were counting on supporters inside the walls, left-wing Muslims associated with the ‘Young Bokhara’ movement. The Emir played the Reds, strung them along, then struck hard. He had the rail lines cut behind them, had their delegation all ambushed and all but two killed, had many of their allies in the city seized and murdered. A massacre of Russians ensued; hundreds were killed. The Reds fired a few shells, then ran out of ammunition. They high-tailed it back to Toshkent. In another scene reminiscent of China Miéville, they had to cover a part of the distance by tearing up railway tracks behind them and laying them down ahead. They signed a treaty with Bokhara on March 25th.

In short: the Reds took Samarqand, but Bokhara stayed independent under its old feudal ruler.

Hell breaks loose

I should emphasise here that most of my information, unavoidably, comes from British and other Western European observers and writers, though Dilip Hiro is more balanced.

Kobozev, the agent sent from Moscow, soon saw his work bearing fruit. In April 1918 the Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Republic was established at a Regional Conference whose proceedings, in an encouraging sign, were held both in Russian and in Uzbek. The ban on Muslims in high government posts was removed (Carr, 338) and ten liberal or radical Muslims were included in the government. (Smith, 192) There were numerous Muslim supporters of the Soviet even from day one, and even prominent Muslim Bolsheviks. (Smele 228) A Kazakh named Turar Ryskulov joined the party in September 1917 and held high positions. There was also the prominent Volga Tatar Bolshevik leader, Sultan Galiev, who led an autonomous Muslim Communist Party. Many people from the Central Asian nationalities had joined the Red Army voluntarily by the end of 1918. (Hiro, 39)

These encouraging developments were rapidly cut across. From May all hell broke loose across the Soviet Union. Central Asia was no exception. The rise of the Czechs, Cossacks and White Guards cut off Toshkent from Moscow. World War One was still raging: a Turkish army advanced on Baku, threatening another key link. There was a Cossack host threatening from the north, a Menshevik-Turkmen government to the west, and British intervention from Persia to the south. A more detailed account of this will follow in the next post.

It is interesting that the bloodshed in Kokand has been neglected by historians and writers, including those whose narratives emphasize revolutionary violence. These events don’t fit the usual moulds of Red Terror, either the excesses of mobs of sailors, or the executions carried out by the Cheka and Revolutionary Tribunals. It resembles more the White-Guard pogroms – a case of racist and brutalised rank-and-file being let loose by the commanders on a defenceless population. It’s not difficult, either, to see in it a continuation of the history of revolt and repression in Tsarist Central Asia since the 1860s.

I have come across no contemporary mention of the Kokand massacre by either White or Red sources. Correspondence from Lenin to President Kolesov amounts to hurried telegrams from the chaotic summer of 1918, guardedly promising help that I assume never materialised. Scholars who have more access or time than me might be able to shine a light here.

Perhaps once Moscow had re-established a stable link with Toshkent and the scale of the settler-colonial violence became clear, heads would have rolled. But by the time that link was made, many of those responsible were already dead and buried. As for how they wound up dead, and how the Toshkent Soviet survived the killing of its key leaders – that, too, will have to wait for the next post.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

The Kokand Massacre, you’re right it’s like something from the Wars of Religion, a Magdeburg or a Drogheda.

LikeLike