This post tells the story of how, having defeated the White Armies, the Soviet Union fought against racism and inequality in Central Asia.

Developments in Central Asia in the early years of the revolution were viewed with mounting alarm by Moscow. The Central Committee of the All-Russian Communist Party warned of the danger of the Soviet regime in Turkestan becoming ‘A Russian Ulster – the colonists’ fronde [revolt] of a national minority counting on support from the centre.’

Readers of the Russian socialist press before the revolution would have been reasonably well-informed on Irish politics (See Lenin’s 1913 article ‘Class War in Dublin’). The ‘Russian Ulster’ remark was made during the Northern Ireland pogroms of 1920-22. In what are known as the ‘First Troubles,’ gangs of loyalists burned a thousand homes and businesses, killed hundreds of people, and expelled Catholics from the Belfast shipyards along with many Protestant trade union activists.

Of course the comparison only goes so far (see the note at the end of this post). But it must have stung the Russian communists in Toshkent because it was true in many ways.

The Turkestan Communist Party was, in 1921, political home to ‘the communist priest, the Russian police officer and the kulak from Semirechie [East Kazakhstan, near China] who still employs dozens of hired labourers, has hundreds of heads of cattle and hunts down Kazakhs like wild beasts.’ In 1920 a veteran Bolshevik, Safarov, wrote: ‘National inequality, in Turkestan, inequality between Europeans and natives, is found at every step.’

And in response to racism in the region’s Communist Party, the minority of Muslim communists became nationalistic. ‘Militant Great Russian chauvinism and the defensive nationalism of the enslaved colonial masses shot through with a mistrust of the Russian – that is the fundamental and characteristic feature of Turkestan reality.’ Thus wrote Broido, another of the few ‘Old Bolsheviks’ of Turkestan, in 1920.

The Congress of the Peoples of the East in Baku, Azerbaijan in September 1920 was a remarkable event in which supporters of the Soviet regime from across Asia gathered, many in their national costume, many having made dangerous journeys. It was remarkable, too, for the spirit of free debate and criticism which prevailed. A Turkestan delegate condemned the ‘inadequacy’ of communism in Central Asia, demanding the removal of ‘your colonists now working under the guise of communism.’

He was met with applause and cries of ‘Bravo’.

‘There are among you, comrades,’ he continued, ‘people who under the mask of communism ruin the whole Soviet power and spoil the whole Soviet policy in the East.’

Safarov repeated the indictment at the 10th Party Congress in March 1921. (Carr, 338, 341)

Moscow intervenes

EH Carr notes that though nationalities policy was discussed at the 8th Communist Party congress in March 1919, Turkestan was somehow not mentioned. Toshkent was after all as far away and as difficult to access as Soviet Hungary. But from July 1919 official statements began to recognise and to stress the importance of Turkestan. It was described as ‘the outpost of communism in Asia.’ With the realisation of its importance came recognition of the crimes and mistakes of the Toshkent Soviet. A 12 July telegram from the Party Central Committee, written by Lenin, insisted on ‘drawing the native Turkestan population into governmental work on a broad proportional basis’ and on no more requisitioning of Muslims’ property without the consent of local Muslim organisations.

The Tashkent leaders were resistant, but as soon as the rail link with Moscow was restored in October 1919, Moscow ‘despatched a team of ideological troubleshooters’ to Toshkent to respond to ‘reports of blood-letting and anarchy.’ (Hopkirk, 79) This official commission insisted that the ‘mistrust of the native toiling masses of Turkestan’ can only be overcome by offering them self-determination, a principle which was ‘the foundation of all the policy.’ Lenin’s further communications stressed ‘comradely relations’ between Russian and Muslim and urged communists to ‘eradicate all traces of Great Russian imperialism.’ (Carr, 339, 340)

Turkestan remained, however, just one relatively small front in a war fought on a continental scale, and Lenin and co were practical. This is unmistakeable in a coded telegram from Lenin to three Toshkent communist leaders dated December 11th 1919:

Your demands for personnel are excessive. It is absurd, or worse than absurd, when you imagine that Turkestan is more important than the centre and the Ukraine. You will not get any more. You must manage with what you have, and not set yourselves unlimited plans, but be modest.

You can look up this stuff on Marxists Internet Archive. A May 25 1920 telegram from Lenin to Frunze consists of a staccato and bluntly practical series of questions about the state of the oil wells. In two August 1921 letters settling a dispute between a pair of communist leaders in Turkestan, Lenin agrees that Moscow must buy ‘nine million sheep’ from Central Asian merchants. ‘They must be obtained at all costs!’ – hence ‘a number of concessions and bonuses to the merchants.’ But the consistent through-line is that ‘the Moslem poor should be treated with care and prudence, with a number of concessions’ – ‘systematic and maximum concern for the Moslem poor, for their organisation and education’ which must be ‘a model for the whole East.’

Some Bolsheviks (notably Stalin) held the idea that only the working class of a given nation should decide the fate of that nation (Jones). The problem with this position is illustrated starkly in Central Asia, where a few thousand foreign railway workers tried to exercise ‘self-determination’ over the heads of ten million Muslim farmers. But Lenin recognised that vast areas of the territory that fell within Moscow’s gravity well were underdeveloped (that is, even more so than the semi-feudal Russian metropole), and that a more sensitive and democratic policy was necessary.

Through 1919, according to Mawdsley (328), Muslims were given ‘more of a role in the state and party, thanks to Moscow’s influence. The centre kept overall control, but more than a semblance of power was given to progressive natives.’ For example, Turar Ryskulov was a Kazakh who joined the Bolsheviks in September 1917 and went on to hold numerous prominent and powerful government posts. (Smele, 333n42)

You might say, ‘Well, Moscow remained in real control,’ but that misses an important point. The peoples of Central Asia articulated demands for autonomy many times, but as far as I can see, demands for independence were few, inchoate and scattered. When they were put forward, they were complicated by being linked to broader identities: pan-Islamic or pan-Turkic ideas.

In January 1920 there arrived the first ‘Red Train’ of party activists fluent in native languages and there was a ‘rapid improvement during 1920’ in the Soviet authorities’ treatment of Muslims.

‘In the winter of 1920-21,’ writes Carr (340), ‘Friday was substituted for Sunday as the weekly rest day, and the postal authorities for the first time accepted telegrams in local languages.’ It’s really shocking that such basic measures were not in place before that time. But at least the ‘Russian Ulster’ was now steadily being dismantled.

Military conquests

Meanwhile the Red Army was consolidating its hold on Central Asia.

The Khanate of Khiva, south of the Aral Sea, had held out against the Reds. In January 1920 the Young Khivans, an indigenous progressive movement, began a revolt and invited the Red Army into the city. The result was the establishment of the Khorezm People’s Socialist Republic.

The new Russian Socialist Federation recognized the Khorezm People’s Soviet Republic as an independent state –publicly renouncing all claims to territory and offering a voluntary economic and military union with the new state. All property and land that once belonged to the Russian state, as well as administrative structures were handed over to the new government with no demands for compensation. Financial assistance was provided to build schools, to campaign to end illiteracy and to build canals, roads and a telegraph system.

The other major feudal power was Bukhara, which in 1920 suffered under famine conditions and under its regressive and violent Emir. In August 1920 the Young Bukhara movement called in the Red Army just like their counterparts in Khiva. There were four days of fighting in Bukhara. By October the Emir was running for the hills to join the Basmachi, while the First Congress of Bukhara workers met in his palace. (Hiro, 41; Carr, 340) There is even a story (Hopkirk, quoting M.N. Roy) that the women of the Emir’s numerous harem each chose to marry a Red Guard after a bizarre kind of speed-dating session.

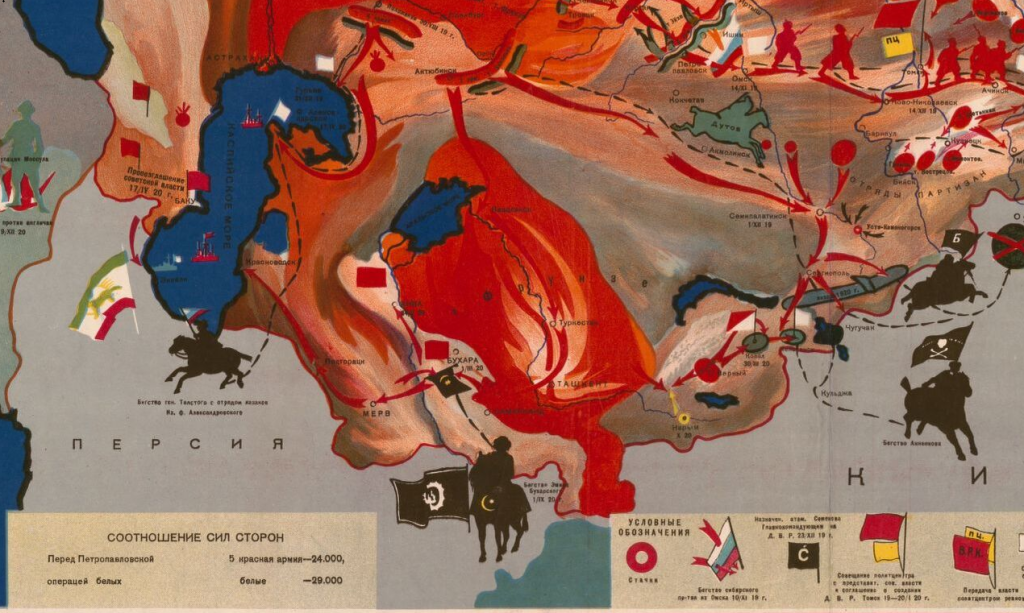

Tashkent. Red spearheads advance throughout as though they were spreading flames. Various centers of authority had arisen in Central Asia following the revolution, but the Red Army managed to turn the region into

a series of soviet republics by the end of 1920. Spread across the region is the name Mikhail Frunze, commander of the Turkestani Red Army, who defeated fierce guerilla opposition to set up a Turkestan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in September 1920.’

In 1920 revolution in Europe was receding as an immediate possibility. Communist leaders turned their attention to the east: there were major independence struggles in India, and in Turkey a guerrilla movement was resisting Allied occupation. In Toshkent there was even a brief attempt to build a revolutionary army of Muslims from the Indian subcontinent.

Social Conquests

The October Revolution did not, as things turned out, attempt to overthrow the British Raj in India, but in the longer term it overthrew illiteracy in Central Asia. For example, in 1926 literacy was only 2.2% in Tajikstan; by 1939 it was 71.7%. 1,600 public libraries were opened across Turkestan. Along with this there was a dramatic rise in the availability of media; newspapers, periodicals, books and radio. Other socio-economic achievements included major road and rail projects and works such as the Fergana Canal.

Red victory in Central Asia brought massive changes to family life, with bans on child marriage and encouragement to women to learn to write. The proportion of women in the workforce in Uzbekistan was 9% in 1925, and 39% by 1939 as women entered into the civil service, schools, colleges, universities, hospitals and labs.

In a 1990 interview with the BBC’s Central Asian Service, a secondary-school teacher reflected on what the October Revolution and its extension to Central Asia meant for her:

I felt I was the luckiest girl in the whole world. My great-grandmother was like a slave, shut up her house. My mother was illiterate. She had thirteen children and looked old all her life. For me the past was dark and horrible, and whatever anyone says about the Soviet Union, that is how it was for me.

She could access free infant healthcare. She could also avail of measures which, in my country in 2023, are not even on the table for discussion: two years’ maternity leave with full salary, and a guaranteed childcare place for her children. (Dilip Hiro, 56)

The revolution in Central Asia was in large part a gender and family revolution, but it was above all a land revolution. From 1920, the major Muslim political parties saw an exodus of members to the Communist Party. Even in rural areas, communism gained popularity. ‘Contrary to the Muslim clerics’ dire warnings […] they [the communists] had concentrated on confiscating the lands of the feudal lords and distributing them to landless and poor peasants.’ (Hiro, 41)

A March 1920 decree returned Central Asian land that had been seized by Russian settlers – 280,000 hectares were given back to local people in a single year. The most notorious racists among the Russian population were deported back to Russia.

From March 1921, the New Economic Policy (NEP) was brought in across the Soviet Union. In Central Asia there was a danger it might cut across land redistribution (hence Lenin’s letters of August 1921 quoted above), but through skilful implementation it was a success. From 1925-1929 there was further redistribution of land at the expense of landlords and clerics. The beks, emirs and khans were simply finished as a ruling class.

Cultural Conquests

Under Soviet rule, the various languages of Central Asia were standardised with Arabic script on a Turkic base of vocabulary and grammar, with the exception of the Persian-influenced Tajik language. Lenin explicitly rejected forcing these languages into Cyrillic script, though as we will see this was later done under Stalin.

For Central Asian languages, this was a historic moment. For example the Kyrgyz language was set down in script for the first time in 1922. (Hiro, 46)

By 1923 there were 67 schools teaching in Mari, 57 in Kabardi, 159 in Komi, 51 in Kalmyk, 100 in Kirghiz, 303 in Buriat and over 2500 for the Tatar language. In Central Asia, the number of national schools, which numbered just 300 before the revolution, reached 2100 by the end of 1920.

[Jones]

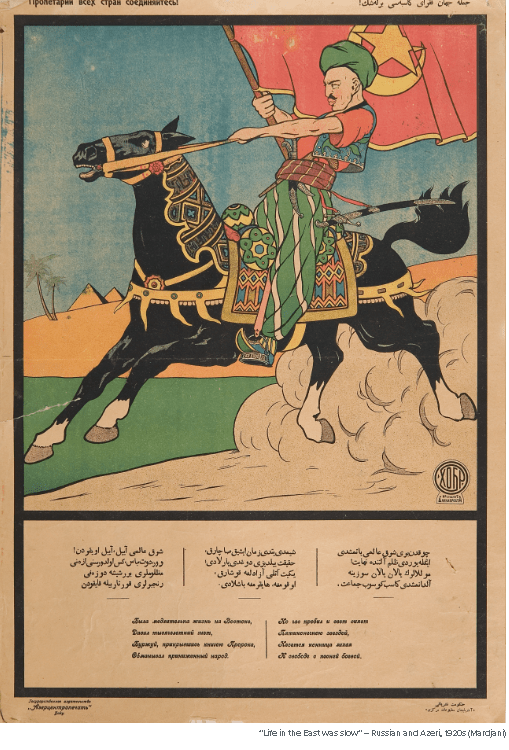

This article by David Trilling from Eurasianet.org points out that the surge in artistic achievement which followed 1917 continued for longer in Central Asia:

The 1920s saw an unfettered flowering of creativity in these regions, especially among Russian-trained artists based in Tashkent and Baku. While central publishing houses in Moscow and Leningrad were shifting to Socialist Realism, artists in the periphery continued the avant-garde movement, combining it with local traditions, according to the exhibit’s curator, Maria Filatova. She sees the colorful posters from the 1920s and early 1930s, with their longer texts and multiple figurines, as direct decendents of local calligraphy and miniature traditions.

Filatova feels the relative freedom of the 1920s makes the work from that decade artistically more interesting compared to what followed. The work is also revealing about that period in early Soviet history, when “socialist ideas coexisted with Islamic ideology.”

Political Conquests

These socio-economic gains were the basis for the emergence of new states in Central Asia.

Early in the Civil War Ataman Dutov, a key White leader in the Urals, recognized the autonomy of the Kazakhs. But when Kolchak took over in late 1918, true to form, he suppressed it. So there was a split between the White Guards and the Kazakh people. In Autumn 1919 the Red General Frunze issued an amnesty for all the fighters of the Alash-Orda who had sided with the Whites; this proved a master-stroke politically and militarily. The Kazakhs came over to the Reds in great numbers and within 4 or 5 months the Reds had advanced all the way across the vast expanse of Kazakhstan.

Moscow quickly recognised a Kazakh Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR). Confusingly, it was at first known as the Kyrgyz ASSR, because Russians ignorantly called the Kazakhs Kyrgyz.

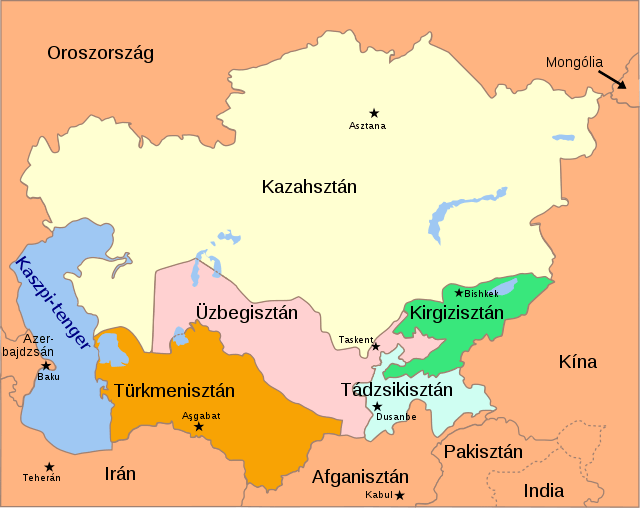

This Kazakh ASSR, population 6.5 million, was the first of the Soviet Republics of Central Asia. The others emerged in the next few years:

- The Turkmens got the autonomous state for which they had been fighting, in the form of the Turkmenia SSR, population one million;

- There emerged the Kyrgyz ASSR, population one million;

- And in December 1926 the Tajik ASSR, population one million, separated from…

- The Uzbek SSR, population 5 million.

The drawing of the boundaries between these new states was not dictated by Moscow, which confined itself to laying down general principles and settling intractable disputes. The actual borders were worked out by local parties and specially designated commissions. Look at a map of the world and at the vortex of convoluted borders between Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan: this was a result of bargaining between indigenous communists. What a contrast to the suspiciously straight lines we see in parts of the Middle East and Africa, drawn up by imperial officials rather than by people with on-the-ground interests and knowledge. (Hiro, 44)

Muslim communists began to come to the fore. But the particular history of Soviet Central Asia also led to particular problems. As outlined above, chauvinism among Russian communists led to a ‘defensive nationalism’ among Muslim communists. This bred further conflict; many of the Muslim leaders who came to prominence in Soviet Central Asia entertained Pan-Turkic ideas as part of that ‘defensive nationalism,’ leading to disagreement between them and Moscow, a struggle which the former lost. (Mawdsley, 332) The Volga Tatar communist Soltangaliev was arrested in 1923, accused of complicity in a Pan-Turkist conspiracy with the Basmachi – an accusation that strikes me as improbable. He was expelled from the party and even jailed, but later released. (Smele, 333n43)

The history of the Soviet Union is sometimes presented as a monolithic story of dictatorship. Certainly the draconian security measures of the Civil War era and the 1921 ban on opposition should not be downplayed, and under Stalin from the late 1920s totalitarian rule was imposed. But as we have seen, even during the Civil War Soviet congresses made important decisions. The Civil War years in fact saw centrifugal tendencies – from Tsaritsyn to Toshkent, local officials turned their noses up at signed credentials from Lenin, and declared that they would do as they pleased. In the 1920s we see some of the potential of Soviet democracy shine through despite extraordinary difficulties such as post-war reconstruction. This is obvious in the case of Central Asia. Hiro writes: ‘the landless, poor and middle-income peasants forming the bulk of the population benefitted economically and politically’ from the extension of the October Revolution to their lands. ‘For instance, in the 1927 to 1928 elections to the Soviets in Tajikistan, the landless, poor and middle-income peasants accounted for 87% of the deputies.’

Conclusion

This post concludes my four-part miniseries Class War and Holy War, a spin-off from Revolution Under Siege. But I’m going to add two short posts to this series, one dealing with the fascinating guerrilla movement known as the Basmachi and another on the impact of Stalinist forced collectivisation and terror in Central Asia.

This series started out bleak and violent. Urban Russia, linked by rail and wire, transplanted the revolution from the Baltic Sea to the Silk Road with remarkable speed. But in Toshkent the Russian population was surrounded by a majority that was of a different religion and of many different nationalities. The workers’ leaders, almost none of whom were developed Bolshevik cadres, filtered the October Revolution through an approach that was at best crude, at worst brutally racist. Instead of combining the anti-colonial revolution with the workers’ revolution, they set the one against the other and risked creating what the Party’s Central Committee termed ‘a Russian Ulster.’

But the Toshkent Soviet did manage to survive a bitter military struggle against many diverse enemies, and from late 1919 the racist element was in retreat. What has been covered in this concluding post really is remarkable: the peoples of Central Asia tore down their ancient lords and shared their land out among the poor; they booted out the worst of the Russian settlers and shared out their land, too; women seized the day; minority languages were revived; the number of healthcare facilities, schools and libraries increased massively; for some years, the people enjoyed free creative expression, democratic rights and real representation; people of different nationalities settled their borders by debate and compromise. Such things really are possible, and in a revolutionary time they can happen quickly.

I’m not describing heaven on earth, and I’m sure the legacy of the Soviet period is disputed and complicated in the diverse countries of Central Asia today, and I understand why the events I have written about might be coloured more negatively in the eyes of people from the region because of later developments. This is a topic I have only begun to look at over the last six months or so, and I feel exactly how I imagine an Uzbek blogger writing about Irish history would feel. While I don’t want to get stuck into comment-section trench warfare, I welcome constructive criticism from people mpre familiar with the region. But it’s difficult for me not to be impressed and even moved, comparing the Central Asian revolution with today’s bitter and violent world with all its bigotry and its apparently intractable national and religious conflicts. Violence and horror are part of history – you didn’t need me to tell you that. But such things as we have described in this post are possible too, even against a background of hate and bloodshed, and they really did happen.

Note on ‘A Russian Ulster’

Speaking of which, here’s a final note about the phrase ‘a Russian Ulster.’ The phrase is inappropriate in important ways.

The first problem is that Central Asia is way bigger, more diverse and more globally significant than Ulster, but because of Anglo cultural hegemony nobody has ever uttered the phrase ‘Ulster is in danger of becoming a British Turkestan.’

Second, the Protestant population in Ireland are not ‘settlers’ but the descendants of settlers from centuries ago, and they have as much of an established place here as anyone. By contrast, the main mass of Russians in Central Asia dated only from the 1890s.

Third, while the sectarian division in Ireland has been and remains bitter and violent, the situation in Central Asia in the early 20th Century appears to have been much worse. I’m sure Northern Irish Catholics and Central Asian Muslims have no interest in competing in the oppression Olympics, but it’s necessary to clarify the limits of the comparison.

Fourth, before the 1920-22 ‘Troubles’ came the 1919 Belfast engineering strike – in which Catholics and Protestants stood together in a strike committee that virtually ran the city. One of several prominent socialist leaders, incidentally, was Simon Greenspon, a man of Russian Jewish background. Here was a glimpse of ‘a Russian Ulster’ in a very different sense.

Lucid and balanced. I do think that if the Bolsheviks used the Ulster comparison one should not be so quick to dismiss it as inappropriate. The industrial working class in both cases provided the sharp end of settler dominance. The argument that a colonial settler community ceases to be a settler community somewhere between thirty and three hundred years after the initial settlement is a limp one. What really matters is the attitude of the settler community and its descendants to the natives. A stronger argument that the comparison is not pertinent would be the relatively greater cultural similarities between Catholic and Protestant and the oh so brief brief flowering of transcendent republicanism in 1790s Ulster. The comparison tells us something important about the determination of Moscow not to set themselves up as the patrons of local Russian communities, however red.

LikeLike

The point about the 1790s and the greater cultural similiarities is a very good one

LikeLike