You lose them in Second Year, around age 14-15.

At 12 or 13 they enter secondary school, where the older students look like adults to them; where far more of the teachers are men than in the primary school; where things seem at once more serious (the sackful of back-breaking textbooks, the timetable) and wilder (the smells of sweat and aftershave, the mass and velocity of the older kids when they mock-fight, the graffiti, the grossness of the graffiti, and the semi-secret places where smoking and vaping happen) and for a while the seriousness and the wildness hold the first year student in awe.

By the time they get into Second Year, the awe is mostly gone. What was serious is now a dull routine and what used to seem wild is now mostly normal. The kids have grown into this new world, have a sense of the pleasures and miseries it offers, what the rules are and which ones they can break. There has always been messing. Now it spreads, quickens.

Next post I’ll talk about what teachers can do to deal with messing. But for now, I’ll mention one of the least effective ways. I’ve caught myself responding to this messing with the same words my own teachers once said to me: ‘You’d better pay attention, because this will be on your Junior Cert.’

There is no appeal more meaningless to a second-year student. Junior Cert? If the second-year even has a clear idea of what that is, they know it’s nearly two years away. Their body will have changed by then. Their social life. Their brain chemistry. All their fantasies will surely have come true by then, elevating them to a state of happiness so perfect that they will not care about exams; or all their worst fears will have come true by then, and the exams will be the least of their worries. A year for a thirteen-year-old feels like a decade for a thirty-year-old.

(I think Classroom-Based Assessments are good, though I only overlapped with them for a few years. They don’t carry much weight in grades, but they do give kids something closer and more palpable to work towards than an exam.)

Second half of Third Year, maybe, you start to see the kids coming back around to you. A few get serious around exams, or just get more mature, or establish a rapport with at least some of their teachers. Through Transition Year, 5th Year and 6th Year, things tend to get better at an accelerating pace. I never had a sixth year class group that I didn’t enjoy teaching.

The most challenging type of student to have in front of you is a TY or a fifth-year who has only matured in the sense that they have gotten more sly, who has only been socialised into the school community in the sense that they know what they can get away with, who has only developed a relationship with teachers in the sense that they have developed a repertoire, an armoury, a tactical doctrine of doing shitty things and dodging the consequences.

Or they have gained immunity from prosecution (I suspect) due to being on a sports team, or (I was told by another staff member) due to secretly being a narc to management.

What is messing?

Let’s walk through some of the repertoire. Some of this is almost innocent and some of it is vile. I’ve thrown it all together to give you an idea of the range of the crap that comes flying at teachers.

Let’s start with second-year stuff: shouting, hooting, laughing weirdly loud; not working; singing; making sex noises; lying down on a row of chairs then ‘accidentally’ falling off; ignoring instructions; making repeated noises with a bottle, chair or pen; asking seven times ‘can we do a Kahoot?’; repeatedly dropping a book on the ground.

Then there’s what John Steinbeck described in Of Mice and Men as the ‘elaborate pantomime of innocence.’ Not content with doing an annoying thing, if the teacher tells the kid to knock it off the latter looks back with wide eyes – ‘Who? Me?’ – and tries to turn the class into a courtroom drama.

Let’s move on to stuff that some second-years will do, but which I associate more with older messers:

Using a watch to reflect a glare into someone’s eyes; saying the ‘F’ slur three times in one period; interrupting and making annoying noises; arriving 25 minutes late and waxing indignant at being asked why; chatting; messing with a phone; or messing with an empty phone cover to wind the teacher up into thinking there’s a phone.

That’s not all of it, I’m just pausing to breathe.

Giving a kid the finger, calling someone an asshole or a fat c*** (or that Polish word that everyone knows, or if you’re a Spanish Lad, hijo de p***); going to sleep or maybe passing out; throwing books; throwing water bottles; throwing a peach; damaging a computer mouse; saying ‘wank’ quietly, then louder, louder, louder; making eye contact with the teacher and silently miming oral sex; doing a racist imitation of another student; calling another student a ‘stupid foreigner’ twice in one class period; knocking over a table; standing up and shouting in the teacher’s face ‘I’ll break the head of ya’; speculating very loudly that a senior staff member is Jewish because of his facial features.

Then there are the various tag team routines – one kid loudly accusing, another loudly protesting innocence; one kid antagonising, another overreacting; sometimes both are in on it, usually only one is.

And there are the routines that come packaged in two halves, set-up and punchline: that one kid who ruins any fun activity you try to do with the class, then complains that the class is too boring; a kid who never does any work, but complains that the teacher is standing in front of the whiteboard (and has been standing there for all of three seconds); the kid who never pays any attention when the teacher introduces the class, then 20 minutes later demands in the most obnoxious tone, ‘what’s the point of this?’; the kid who takes a ‘toilet break’ and disappears for twenty minutes; next week he demands another ‘toilet break’ and when it is denied he thinks he’s Alexei Navalny; the kid who is constantly chatting, and complains that someone else is chatting, and demands that you punish them.

This is all stuff I’ve seen with my own eyes in TY and fifth-year classes. And some teachers will tell you ‘that’s nothing.’ But if you want to do something fun, you can selectively quote the above list, mentioning only the most trivial stuff, and make out teachers are whingers, etc.

The thing about some of the more trivial stuff is, the teacher doesn’t have to take any stern measures when it’s the odd isolated innocent thing. But there are students who will throw this stuff at you relentlessly. Most kids? Absolutely not. But enough that, I’d say in most classrooms, the atmosphere can be spoiled if the teacher isn’t working hard to counter it.

I have another fun suggestion for you: you can fantasise about the amazing, perfect and macho way you would have ‘put manners on those kids,’ implicitly judging me (and teachers generally) for ‘allowing’ any of this crap to happen in the first place. But what I did, and what worked and what didn’t, is a topic for the next post.

Why do kids mess?

Why do some students disrupt classes and start rows with teachers?

A good place to start: why did you mess in school? Everyone did. I messed badly in the last year of primary school – not sure what that was all about, in hindsight – probably hormones. In secondary school, I messed in Maths class – not working, drawing pictures, chatting – because I was terrible at the subject. I messed when those around me were messing. I chatted and joked when the kid sitting beside me wanted to chat and joke – I didn’t want to be a dick to teachers, but it would be rude to blank your friend. I mitched a bit towards the end of Third Year, through a lot of TY, and towards the end of Sixth year, because I had a sense that I wasn’t hurting anyone and wouldn’t be caught.

Moving on to what I’ve observed as a teacher. Why do kids mess?

A working-class or poor student sometimes resents the teacher as a representative of a state they instinctively (and correctly) feel is the property of the rich. They might have a fundamental lack of trust in state institutions, and schools in particular, because of their own or their parents’ experiences.

And the school is not just the state. It’s also the church. Of the seven or eight schools I taught in, only two were secular. The rest all had elaborately Catholic names, statues of Mary, crucifixes on the walls, school masses. This wouldn’t be too shocking to Spanish Lads or to Polish or Lithuanian students. But for others, it’s got to be strange and alienating.

[As an aside, I’m pure disgusted with Enoch Burke, a worse messer than the most challenging kids I ever taught. I’m an atheist since age 20, but I went to school masses and paused lessons for prayers over the intercom. I didn’t confront school principals, loosing spittle in their faces as I ranted about the ways the school mass or the picture of Jesus at the back of every classroom troubled my conscience. I can be a secularist while picking my battles, respecting other people’s religion and not making everything all about me. And Burke can nurse his conspiracy theories about ‘gender ideology’ without turning a child’s personal journey and a school community into a circus.]

That was how I understood things at first – that students are alienated from education for very good reasons. There’s plenty of truth in that. But I haven’t observed that non-Catholic students are more prone to messing. Likewise it would be extremely unfair to working-class students to say they are behind more than their share of the messing.

On the contrary, I have encountered kids who picked up from their parents a feeling of superiority to mere civil servants. There are kids who view their teacher as a person of humble origins who has landed a cushy job, and who deserves to be tormented on that account.

‘Imagine being paid less than a binman,’ a kid of sixteen or seventeen once said in my class. He obviously intended me to hear. ‘Starting-out teachers get paid less than a binman.’ I don’t know if that’s true and I’ve never checked because I don’t care. If it’s true, good for the bin collectors. But that remark gives an insight into that kid’s disgusting attitudes, and helps explain why he was one of the most obnoxious students I’ve ever encountered.

Gender is another angle. I won’t comment on the sexism that (no doubt) women experience in teaching, because I want to stick to my own experiences.

I did come up against macho bullshit rooted in ‘traditional gender roles.’ There are boys who appear to believe that if they follow instructions from another male it’s basically a public humiliation. I have absolutely no interest in being the ‘alpha male’ or whatever . But when everything you do is interpreted through a worldview that reduces everything to dominance hierarchies, learning is the last thing on the agenda.

Sometimes this helps produce kids who are on a hair-trigger. I imagine most of them end up expelled. But often it’s milder, taking the form of a skirmish with the male teacher. Let’s say the result is a draw. Honour is satisfied. The boy, having made it clear he can push back if he wants to, chooses now to co-operate. The teacher, who just wants to get on with the class, forgives even if he doesn’t forget.

Students who rebel against teachers are not all products of toxic masculinity. Sometimes teachers behave in unfair and cruel ways, and the kids are not wrong to push back. Sometimes a kid’s strong sense of justice can explain their behaviour.

I’m not qualified to say much about neuro divergence. But it appears to me that with some kids, their brains scream at them to seek attention, to move and make noise, to seek the dopamine rush triggered by transgression and conflict. Often kids are not diagnosed, or even if they have a diagnosis their teachers are not always told. You often find out about a diagnosis, whether it’s ASD, ADHD or a Learning Difficulty, randomly in staff room chat.

Kids with a diagnosis do usually get resource hours and SNAs. In the classroom the teacher might have prior experience, but does not always have basic information and usually doesn’t have any training with regards to particular conditions. It goes without saying that the teacher doesn’t get any extra time or resources. No wonder so many kids, even plenty who don’t have any specific condition, fall behind.

Social problems from outside school invade it all the time. Crime, drug abuse, domestic violence. Some students have terrible lives outside school, and they come in and use their teachers as emotional punching bags.

Some students will annoy you one day, and be your best friend the next. Sometimes it’s pure manipulation. Usually it isn’t. This is because human beings are funny, and being a teenager is very difficult.

Kids mess because they are bored or resentful. This can be the teacher’s fault for preparing dull lessons, or not preparing at all. But it’s a vicious cycle sometimes. You have a class whose behaviour is very challenging, so you don’t try to do anything fun or easy-going. You know there are five or six kids who will take advantage and just plunge the whole classroom into chaos. This leads to more boredom, more alienation. But I don’t know what else one can do.

Likewise, kids mess if they feel their teacher is arbitrary and unfair. But when you’re dealing with a very challenging class group, you might come across as arbitrary and unfair without meaning to. The cycle continues.

A teacher feels vulnerable writing about this stuff, leaving themselves open to being judged for not ‘controlling the class,’ whatever that’s supposed to mean. But it’s a massive issue in secondary education.

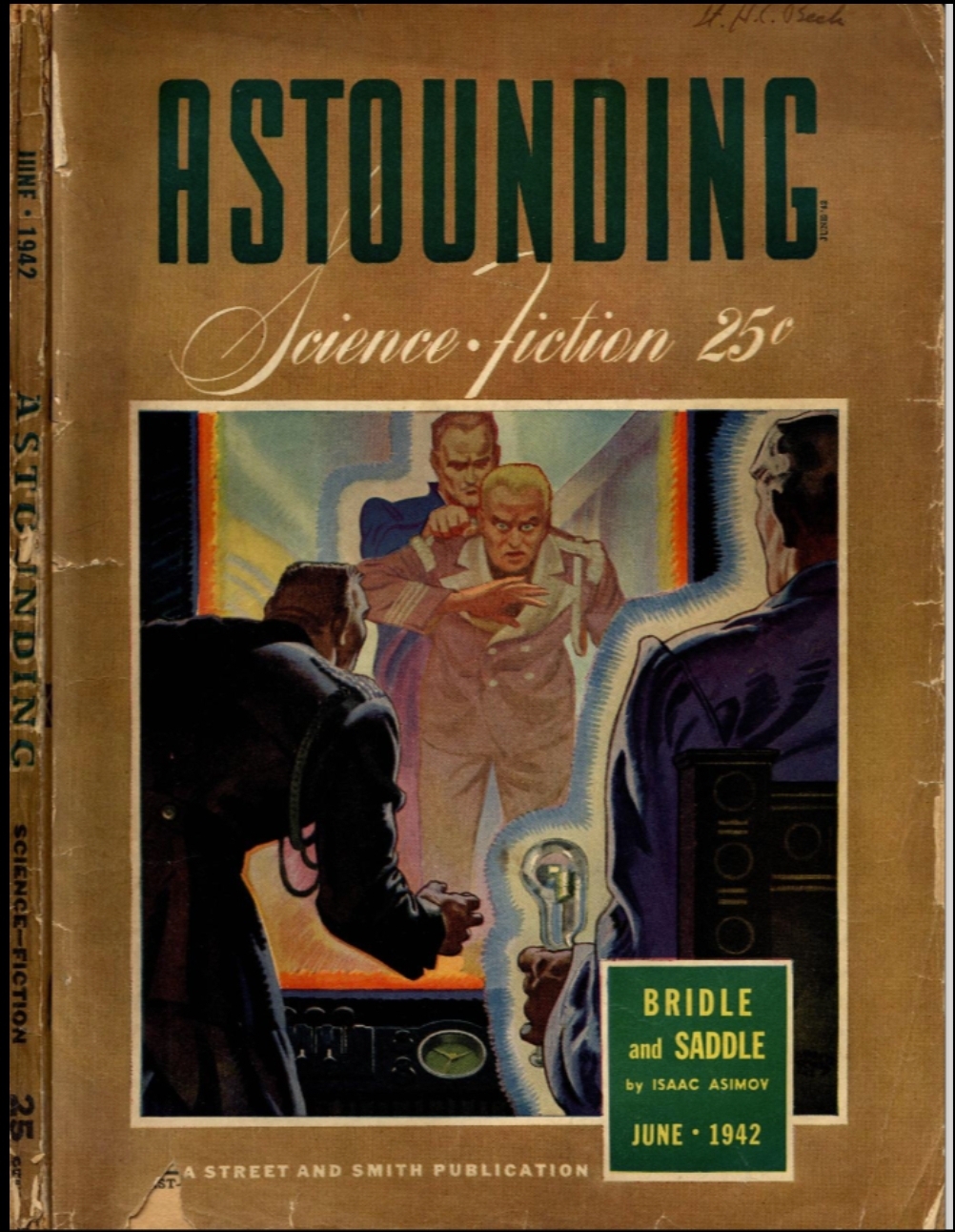

The system largely creates ‘messing.’ Education has come a long way since the early 20th Century. But even though progressive ideas have been layered on top, the foundation is the same: there is an expectation that the teacher can make twenty-five young people behave in a strictly regimented way. The problem is the ridiculous idea that two dozen fifteen-year-olds can be made to not mess by a single adult who does not possess superpowers and who is – thankfully – not allowed to assault kids anymore. The basic set-up pits kids and teachers against each other right from the start.

So, confronted with behaviour that makes it very difficult to do our jobs, teachers have few good options. Next time we’ll look at what teachers can do under the status quo, and explore how things could be different and better.

Go to Home Page/ Archives

Did you enjoy this post? Please subscribe to get email updates: