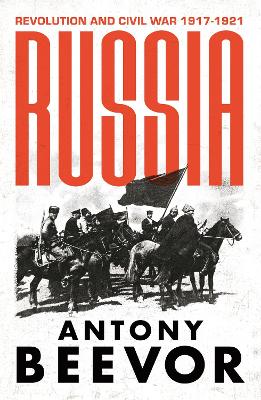

I learned a lot from Stalingrad and The Battle for Spain, so I was interested to learn that Antony Beevor was tackling the Russian Civil War in his latest book.

But judging from what I’ve read so far, Russia: Revolution and Civil War 1917-1921 is a crude offering. I’ll show what I mean by reference to a single chapter (which is more or less all I’ve read).

When I looked at the contents page, my eye was drawn to a chapter titled ‘The Infanticide of Democracy, November-December 1917.’

If you’re going to put an image of infanticide into my head, you’d better have a good reason. In this case, there is no good reason: during those two months, November and December, the Bolsheviks secured a majority in the Soviets, then received the blessing of a peasant soviet congress. They passed decrees on peace and land. They went into coalition with the Left SRs. They held the Constituent Assembly elections. The street fighting lasted only a few days, and the Whites involved were in general treated with magnanimity. Throughout, the Bolsheviks resisted the pressure to enter coalition with parties whose programme was diametrically opposed to theirs, and relied instead on the active support of millions of people.

All in all, I see this period as one during which, against challenging odds, the new soviet government lived up to its promise. But Beevor doesn’t see it that way.

Peace

He starts out talking about the war. Even though he dubs World War One ‘The Suicide of Europe’, he condemns the Soviets for trying to end the war. For him, the peace efforts were a bad thing because they encouraged rowdy and violent deserters (as if the rotten Tsarist army was not already collapsing due to mass desertion). If the Bolsheviks had broken their peace promise and forced everyone to fight on at gunpoint, no doubt Beevor would condemn that too. And he would be right!

Next in line for condemnation are the deserters themselves – because they ripped the upholstery out of first-class train carriages to wrap around their bare feet. Unmoved by the bare feet of the soldiers, Beevor is moved by the plight of the upholstery.

It must be fun for Beevor to come up with these taboo-busting chapter titles. ‘The Suicide of Europe,’ ‘The Infanticide of Democracy’… What’s next? ‘The Incest of Asia’? ‘The Opioid Addiction of Oligarchy’?

Plotting Civil War

Lenin, Beevor tells us, ‘welcomed destruction for its own sake.’ From there, he argues that Lenin wanted to start a civil war – ‘to achieve tabula rasa through violence,’ that he wanted all the horrendous destruction and inhumanity of 1918-1921 to happen so that he could ‘retain power’ and build communism on a clean slate.

So according to Beevor, Lenin’s plan was to hold power and to build communism in a context where the industries were devastated, where the areas which produced food and raw materials were occupied by enemy armies, where the urban working class – his support base! – were dying in huge numbers, where military spending made it impossible to pursue ambitious social programmes. Needless to say, this was not his plan.

By April, Lenin was happy (an unfortunately very wrong) to declare that the war was over. The idea that he wanted the Civil War at all is just as absurd as his alleged motivation.

But Beevor ‘proves’ his contention by cooking up the most negative and hostile interpretations of carefully-selected utterances by Lenin, then presenting these interpretations as fact.

You can feel Beevor’s fury and disgust every time he mentions Lenin. Whenever we see that name, it is accompanied by a bitterly hostile remark. He must have damaged his keyboard, angrily banging out L – E – N – I – N again and again. And yet to Lenin he keeps returning, as though the revolution revolved around one man.

Food

He ridicules Lenin’s claim that wealthy people were sabotaging food supplies. But this sabotage was taking place. First, there was speculation, or in other words the hoarding of food to drive up prices. Second, there was the strike of government employees, which was creating a humanitarian crisis, the sharpest edge of which was a food shortage. This strike was financed by rich people and big companies, and collapsed when they withdrew their support.

In a context of looming famine, when Lenin calls wealthy people ‘parasites’ and calls for a ‘war to the death’ against them, Beevor says this is ‘tantamount to a call to class genocide.’

The blind spots Beevor reveals are interesting. In this passage he talks about two things: 1) rich people starving poor people to death, and 2) Lenin making an inflammatory speech. If you asked me which of those two things could best be described as ‘class genocide,’ I know which one I’d pick. But for Beevor, it’s the first-class upholstery all over again. He gets upset about dangerous words and not about empty stomachs.

The food supply crisis, naturally, he blames on the Bolsheviks – even though the food crisis had been getting worse since 1915 and the Bolsheviks had been in power for all of five minutes.

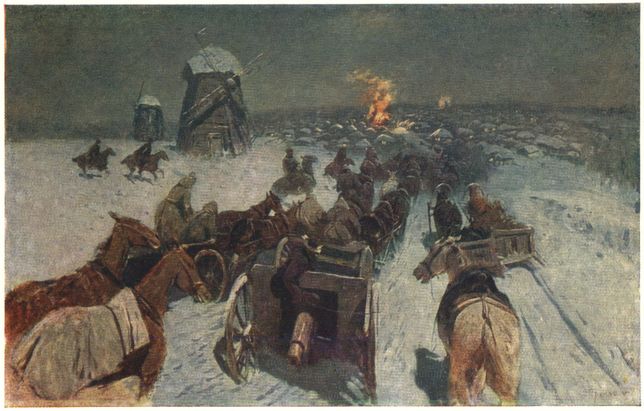

Kornilov

The author turns his attention to the right-wing General Kornilov, who broke out of prison and rode across Russia to the Don Country where he met up with thousands of other officers and set up a rebel army to fight the Soviet government. His descriptions of Kornilov in this chapter make him sound like a fearless adventurer whose only fault is that maybe he’s too brave. There were ‘innumerable skirmishes.’ No doubt if it had been Lenin fighting his way across the country Beevor would pause to describe the blood and guts of his ruthlessly slaughtered victims. Instead of this, he compares the whole thing to Xenophon’s Anabasis (That’s The Warriors to you and me).

Lenin is portrayed as plotting to start a civil war. But Beevor never ventures to speculate that maybe Kornilov is plotting to start a civil war. Apparently Kornilov is fighting his way across the country and raising a rebel army for some other purpose.

Beevor’s version of Lenin can only retain power by achieving ‘tabula rasa through violence’ – as opposed to retaining power by democratic means. Meanwhile what was Kornilov doing, and why does it not come in for any scrutiny?

Lenin’s power rested on the active support of many millions of people through the Soviets, which were at this stage still a robust participatory-democratic system. Meanwhile Kornilov’s power rested on the support of several thousand men who gathered by the Don river at the end of 1917. They were united in the conviction that no elections were possible in Russia until the country was ‘purged’ and ‘cleansed’ of the soviets, along with nationalist movements and minorities.

In other words, they wanted to achieve tabula rasa through violence. But, at least in this chapter, it does not occur to Beevor to present them in this way.

Anti-Semitism

The most dishonest part of the chapter comes with Beevor’s remarks on anti-Semitism. He relates two local episodes in which soldiers and sailors attacked Jewish people. These incidents are supposed to prove that the Soviets tolerated or even encouraged anti-Semitism. We read: ‘Soviet authorities tacitly condoned violence against Jews’!

But just a few pages earlier, Beevor writes at length about the foundation of the Cheka. Somehow he fails to mention that one of the main purposes for which the Cheka was founded was to combat anti-Semitic pogroms. The very incidents he describes may have been those which the soviets responded to by setting up the Cheka.

Nor does he mention the outlawing of all racist discrimination, including anti-Semitism, by the new government.

The Cheka

The Cheka during November-December 1917 was a security organisation with only a few dozen full-time staff. But Beevor writes of it as if it were already the feared and controversial instrument of terror that it became over the year 1918. No, scratch that, he writes about it as if it were already the NKVD under Lavrentiy Beria.

For example, he quotes a poem which he says was ‘later’ published in a Cheka anthology. This is a disgusting, psychopathic little poem which celebrates killing. What Beevor doesn’t mention is that this poem was published a lot later, 1921 at the earliest. The entire Civil War took place between the point we’re at in the narrative and the date when the Cheka published this unhinged poem. Four years is an age in times of revolution and civil war. This poem was not written or published in December 1917 and could not possibly have been. The brutality it reflects was a product of the Civil War. Beevor presents it as if it were a cause of that war, part of the ‘infanticide’ of democracy, as if that mindset was there from the start, was in the DNA of the Cheka.

After the Civil War, by the way, the Cheka was radically downsized. Its role, under different names and big organisational changes, as Stalin’s executioner was yet another even later development.

By jumping around in time like this Beevor doesn’t just present a misleading account. He tells a dull story, a smooth and frictionless history of the Russian Revolution. Stalin’s totalitarian state is already there, fully-formed, in November 1917.

The Bolsheviks were initially humane and even magnanimous. Utterances from revolutionary leaders in which they speak in military metaphors can be easily found. But it is just as easy to find them expressing the hope that the Russian Revolution would be a lot less bloody than the French (so far, it had been). Krasnov was paroled after attacking Petrograd. Many Whites who fought in Moscow were let go and allowed to keep their weapons. Lunacharsky was so horrified by the fighting in Moscow he resigned as a minister. Lenin was the victim of an assassination attempt in January 1918, but it was hushed up at the time so as not to provoke reprisals. But 1918 saw Kornilov and his successors, along with foreign powers and the Right SRs, create a terrible military, political and humanitarian crisis in a bid to crush the soviets. This was the context for the development of the Cheka into what it became.

But in the monotonous world in which this chapter takes place, there is no change, no development of characters or institutions. A is always equal to A. The Cheka is always the Cheka. This way of looking at the world may pass muster in a book where, for example, Guderian’s Panzer Corps remains for a long period a dependable, solid and unchanging entity. But it is ill-suited to talking about revolutions and civil wars, in which institutions can pass through a lifetime of changes in a few months.

It’s not just that he gives a misleading, flattened account. It’s that he misses an opportunity to tell a far more interesting story.

The Left SRs

To minimise the significance of the coalition, Beevor treats the Left SRs as a bunch of ineffectual idiots and claims that the Bolsheviks always got their way. In fact, many of the key early leaders of the Red Army and Cheka were Left SRs; all Soviet institutions were shared between the two parties, for long after the coalition broke up in March 1918, and even after the Left SR Uprising of July 1918. But here Beevor treats the Left SRs just as he treats the Cheka: by jumping around in time as if context does not matter.

It’s real Doctor Manhattan territory. It is December 1917, and the Bolsheviks and Left SRs are making a coalition; it is March 1918, and they are breaking up over the Brest Treaty; it is July 1918, and they are shooting at each other in the streets of Moscow.

It gets worse. We are informed that ‘Leading Left SRs also fought for the distribution of land to the peasants, against what they now suspected was the Bolshevik plan of outright nationalisation.’

They ‘fought’, did they? Against whom?

Collectivisation, let alone ‘outright nationalisation,’ of land was not attempted, and it certainly was not an issue in the Bolshevik-Left SR split. Local experiments in state farms, and certain ultra-left policies in Ukraine and the Baltic States, are the only thing that comes close to what Beevor is suggesting. Stalin’s policy of forced complete collectivisation, meanwhile, was ten years away, and was never even contemplated by Lenin.

When Beevor writes that Lenin ‘had shamelessly copied’ Left SR policy on land, he is committing a double absurdity. First, because Lenin’s own position on the land question, consistent over twenty years or so, was broadly the same. Second, because the rules of plagiarism and copyright do not apply to policies. Adopting the policy of another party is a concession to that party.

But that wouldn’t do for Beevor. He cannot show Lenin being agreeable in any way. He insists that Lenin was like an icebreaking ship, that he was a worse autocrat than Nicholas II. Whenever Lenin’s actions contradict the extreme characterisations, Beevor cooks up a sinister motivation, rather than just reassessing his views, or admitting that politics and history are complex. The coalition with the Left SRs? A nasty trick. The Constituent Assembly elections? ‘Lip service.’ Soviet democracy? He claims it was ‘sidelined’ even though Soviet Congresses continued to meet and to decide key questions of policy well into the crisis of summer 1918.

Every narrative trick in the book is on display in this chapter. For example, Beevor describes the Left SRs getting in on the ground floor of the Cheka in a way that would leave an unattentive reader with the impression that they had been excluded. He describes up as down and black as white.

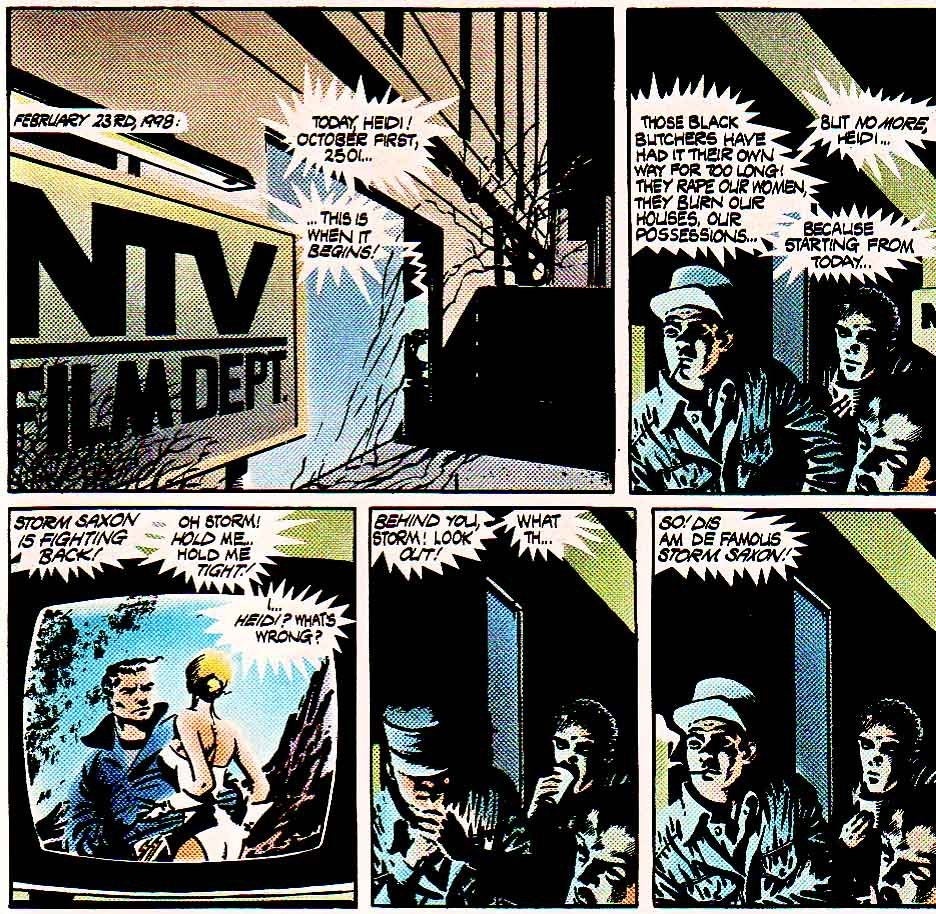

Persia

I’m disappointed. I was actually interested in reading Beevor’s account of the Civil War. I did not expect to agree with all or even most of what he said. But I thought he’d have something to say, and that it would enrich my own ongoing series on the Russian Civil War. Instead we get this monotonous, unbalanced condemnation that we’ve heard so many times before from so many sources: school, TV, and books with gushing quotes in their blurbs. The same old story is invariably described in these gushing blurbs as fresh and challenging.

Two-thirds of the way through, the chapter changes tack. It follows the critic Viktor Shklovsky as he runs off to Persia at around this time. This was horrifying reading, but at least I learned something I hadn’t already known. The Tsarist army was in occupation of a part of Persia, which was a major contributor to the fact that a third of Persia’s population died of famine and disease during the First World War. The Russian soldiers shot civilians for fun, abducted women and sold them in Crimea. Beevor notes that there was a different going rate for women who had already been raped and for those who had not.

Horrified, I read an article going deeper into this. Here – it seems by accident – the title ‘The Infanticide of Democracy’ earns its place. The Persians had a democratic revolution in 1909. Russia and Britain could not tolerate the possibility of an independent Persian Republic. They invaded, supported the reactionaries, and slaughtered thousands.

The horrors of the Tsarist occupation of Persia should give Beevor pause for thought. Was Lenin really ‘a worse autocrat than Nicholas,’ if this is what Nicholas did to Persia? These killers and slave-traffickers were many of the same officers and Cossacks who staffed the White Armies. If the Reds were fighting against such a heavy legacy of oppression, shouldn’t even a consistent liberal historian cut them some slack?

Beevor does not mention (at least in this chapter) that the Soviets renounced any Russian claim on Persian territory, and withdrew what was left of the Russian army. I had to learn that from the article linked above. But if he did mention it, no doubt he would find a way to twist it into something sinister and evil.

Conclusion

A lot of this chapter is taken up with abstract little sermons like the following: ‘This summed up the Bolsheviks’ idealised ruthlessness, elevating their cause above any humane concern such as natural justice or respect for life’ – or upholstery.

I don’t want the reader to think I have it in for Beevor just because I disagree with him. My shelf and my devices are full of titles whose authors I disagree with. Take the following remark by Laura Engelstein from her introduction to Russia in Flames: ‘there were no halcyon days of the Bolshevik Revolution. There was no primal moment of democratic purity that was later betrayed.’ I disagree with this statement, but at least there’s something there with which to disagree. It’s not a strident condemnation, let alone the third or fourth strident condemnation on a single page.

Evan Mawdsley’s book answers all kinds of fascinating questions about the Russian Civil War. It does so in a way that’s biased toward the Allies, but which leaves space for the reader to disagree, which often gives the other side the best lines, etc.

I have no problem, obviously, with polemical or agitational or partisan writing. But Beevor batters us over the head with his opinion and leaves us no space to interpret what he tells us. He writes in a ‘take it or leave it’ manner that does not invite debate. If he’s writing about 1917 and can’t find the evidence he needs to shock you into submitting to his point of view, he’ll go as far as 1921 to get it, then neglect to tell you where it came from.

I don’t know whether it’s complacency – he believes that he has a water-tight case, so he makes it with maximum force – or anxiety – he has serious doubts about what he’s writing, so he leaves no room for the reader to make up their own mind.

To sum up, the first part of the chapter was about a government that was trying to end World War One, share land with the peasants, and give power to workers’ councils. The author could hardly contain his rage and disgust. The end of the chapter was about a Tsarist army mass-murdering Persian people for eight long years. Here the author suddenly dropped the sermonising, the angry tone, the condemnations. Without his stranglehold on the narrative it was easier to read, in spite of the horrors he was describing. But the sudden shift in tone – oh man, it spoke volumes.

I have a sinking feeling that the whole book is going to be like this.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

Go to Home Page/ Archive