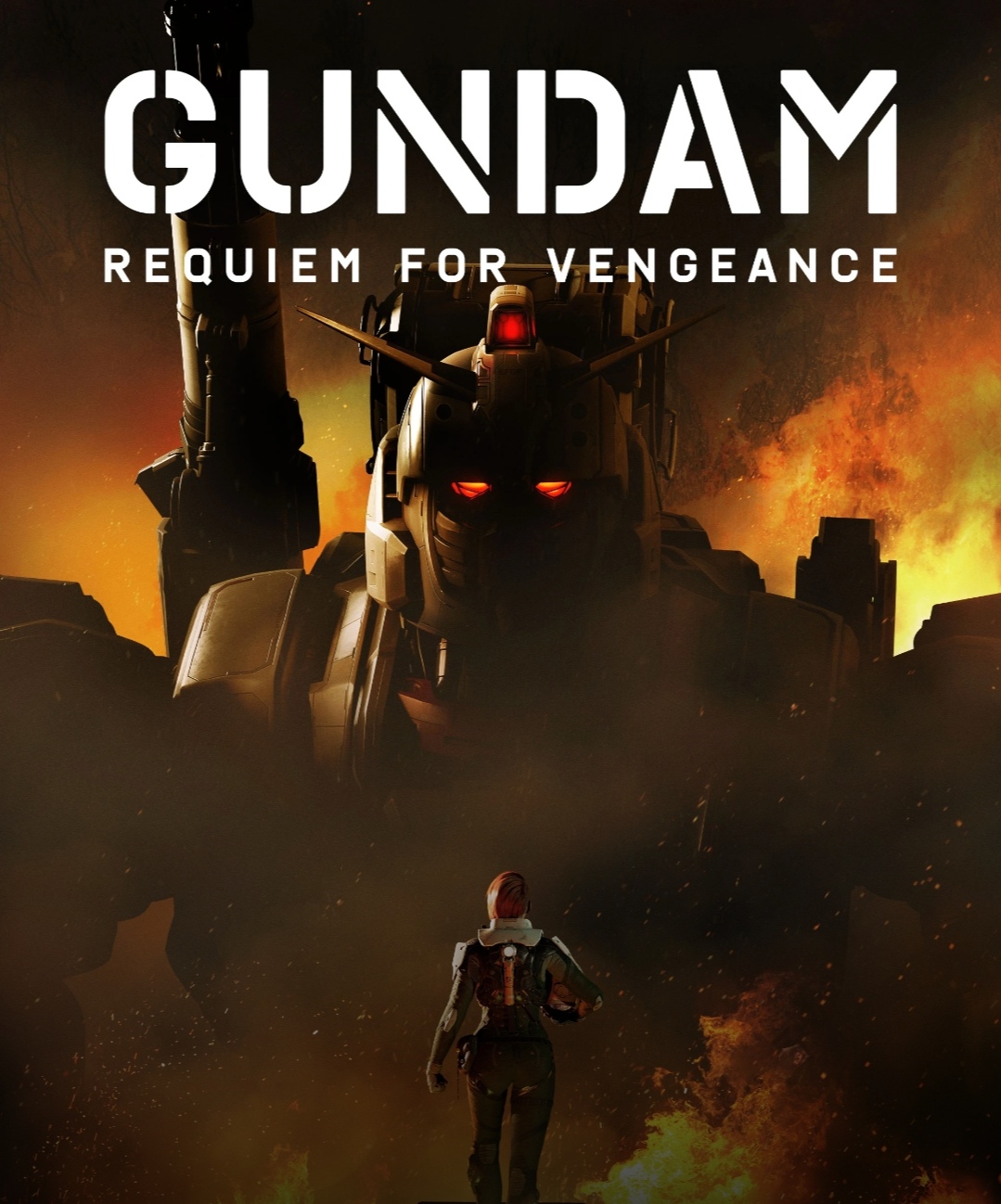

We’ve got a guest post for you today, a review of Netflix’s Gundam: Requiem for Vengeance by freelance writer Charlie Jean McKeown.

Stories and machines are ultimately driven by people, yet Gundam: Requiem for Vengeance lacks the personality needed for the gritty mecha war drama it tries to be. Since its 40th anniversary, the Gundam franchise has been boasting ambitious projects like SEED Freedom (2024) in theatres, Witch from Mercury (2023) on TV, and in gaming Gundam Evolution (2022). (i )

This new Netflix series follows Zeon soldiers- the usual antagonists- in the closing months of the ‘One Year War.’ It’s an attempted love letter for Gundam fans, with a touching homage to the original 1979 show in its opening titles and what must have been a laborious effort to give the classic mecha designs such glorious detail. However, Requiem has little identity of its own; it has little to offer old fans and nothing accessible for new ones. More disappointingly, it does open up genuinely interesting themes which could have given the show some life if they were navigated by decent characters.

Requiem actually inverts some of Gundam’s most central themes; empathy becomes vengeance, and our protagonist is an enlisted mother rather than the usual child soldier. ‘Time’ is not a new theme for the franchise but had never received the same attention it enjoys here albeit with some overly-obvious motifs. The survival element of other Gundam series is heightened in Requiem too, as we watch the losing side struggle against a war-winning weapon. These themes, though, are only minimally engaged with. While one could blame this on the many action scenes, Gundam has always used battles to deepen its narratives rather than merely embellish them. Furthermore, Requiem still has plenty of peaceful moments in its three-hour runtime. The fault is really found in the show’s repetitive exposition soaking up what should be time spent on challenging characters so that they may develop and investigate these concepts.

All of this culminates into the most disturbingly mishandled theme of Requiem: nationalism. Mirroring the Cold War narrative of Nazi Germany (ii), Zeon had always been presented as an evil fascist regime with ordinary soldiers fighting for their homes. Interestingly, the One Year War – the definitive conflict of the franchise – is renamed here as ‘the Revolutionary War.’ Is this how the fascist Principality of Zeon sees itself? Do they view the One Year War the way Confederates saw the American Civil War? It’s a fascinating angle to investigate. However, it feels like Requiem takes up a ‘both sides matter,’ approach, with no real discussion of Zeon’s war crimes (wiping out half the Earth’s population, for instance). Instead, our apolitical protagonist is “just following orders.” While her final monologue is clearly intended to convey a lesson she learnt, it gives us a rather warped justification for continuing to fight under a swastika-esque banner.

While the writing is poor, Requiem’s establishing shots want you to know money and effort went into making them. Requiem is Gundam’s first CG animated production since MS IGLOO (2004), and the improvement in quality is staggering. By tightening their dimensions, the old mecha designs remain credible in today’s science fiction scene while the body language of these giants conveys a surprising degree of emotion. The facial animations are unfortunately less expressive, and to come across they often rely on the wonderful new soundtrack provided by award-winning composer, Wilbert Roget II. Netflix’s first Gundam production does look lovely as a whole, but its writing encourages little confidence in the live action film they announced in 2018. I doubt Requiem will see a second season, which is a terrible shame given its potential; if the writers could make some course-corrections in a new season and rummage through those ideas they raised, then Gundam: Requiem for Vengeance could be forgiven for these first six dismal episodes and actualise its own distinct identity.

(i) While Evolution was closed down in a year, it gave Overwatch 2 a little competition in the hero-shooter market

before collapsing under its embarrassing micro-transactions.

(ii) A narrative, it should be noted, now being revised by historians who are acknowledging the Wehrmacht’s

complicity in war crimes.