For your convenience, all the maps from Series 2 gathered together on one PDF:

21: Red Cavalry (Premium)

‘[T]he Bolsheviks are failing… their regime is doomed.’

Winston Churchill to Lord Curzon, Autumn 1919 (Kinvig, Churchill’s Crusade, p 305)

January 15th, 1920

The date by which, in Autumn 1919, British military officials predicted Moscow would fall to the Whites

‘Na konii, proletarii!’

‘To horse, proletarians!’ Red Army slogan, 1918-1919

Become a paying supporter to get access

Access to this article is limited to paying supporters. If you already subscribe by email, thank you. But if you want to become a paying supporter, please hit ‘Subscribe’ below.

Donate less than the price of a coffee, and you can access everything on this blog for one year.

If you don’t feel like donating, most of my posts are still 100% free, so browse away, and thanks for visiting.

Review: The Witcher: Blood Origin

So it turns out The Witcher is better without The Witcher.

A long time ago I watched the first 3 or 4 episodes of The Witcher and never warmed to it. I liked the monster fights. But the production varied in quality from ‘dripping with Gothic atmosphere’ to ‘just plain tacky.’

The prequel series Blood Origin caught my attention by accident over the Christmas. Now, since watching it I’ve tried to read a review or two to find out why so many people (but not everyone) hated it. This one from Polygon was largely incomprehensible to me. It’s not just that I disagreed; I did not understand what the criteria were by which the series was being judged.

To my eyes, it was not a series that undermined the precious canon or a mess of a story which invited me to pick it apart to explain how it failed. It was a pulp swords-and-sorcery adventure which looked and sounded good, which had a cast of fun, engaging characters, which was focused and disciplined at a tight four episodes. The class war elements set up in the first episode with the rabble-rousing song ‘The Black Rose’ paid off in spades at the end when a revolution was part of the final showdown.

That review from Polygon says: ‘There’s a class conflict that keeps getting hinted at through a song Élie [sic] is famous for, but there’s never much consideration of what that actually means, in-universe, beyond “lower-class folks are hungrier than their elite counterparts.”’

I said of Andor that I didn’t need it to be a Ken Loach film. Well… I don’t need a three-hour fantasy story even to be Andor, let alone Ken Loach. The class war element was not at all simplistic – it was just focused and coherent.

One last quote from that review: ‘When Élie promises Scían the chance to reclaim the sacred sword of her people, it’s introduced in the conversation with no explanation for how Élie would’ve even known it was gone.’

Not only did that not bother me, it didn’t strike me as a thing which might conceivably bother anyone. Éile has lived in this world all her life and presumably knows about various things. If she has shoelaces (I can’t remember) she probably learned to tie them at some point in her life, but we don’t need a flashback explaining this.

Who first came up with the trope of making Elves speak the Queen’s English? In this, the elves have Welsh, Irish and other regional accents. If that’s a feature of The Witcher (I can’t remember) then good for The Witcher. Tolkien-variety elves are a mythical reflection of Celtic peoples as seen through Anglo-Saxon eyes.

They got the tone just right. It doesn’t take itself too seriously, but then it doesn’t let silly banter undermine the serious moments either. After just two and a half episodes, we get a sequence where the seven adventurers sit down and have a party. That strikes me as a difficult thing to pull off; the writers have got to warm the viewers up to the characters and the characters to each other. Blood Origin pulled that off.

The cast was uniquely diverse. I say ‘uniquely’ because off the top of my head I can’t think of another TV series or movie in the genre that does such a good job of reflecting the diversity of our species in its cast.

I felt it could have gone on just a bit longer, another episode or two, and that the promised ‘Conjunction of the Spheres’ ended up being skimmed over. Neither of these things was a deal-breaker for me; in fact I was relieved that it wasn’t a sprawling, incoherent mess that was too busy setting up hypothetical future seasons to tell its own story. I could forgive it for erring in the other direction.

Finally and crucially, I was relieved that platinum-blonde Solid Snake was nowhere to be seen. I don’t want to criticise The Witcher too much because that would be churlish in this context. Geralt of Rivia has an iconic look, I suppose, but I never found him interesting in my limited exposure to the show. His absence leaves a lot of room for other characters to throw their weight around.

Anyone familiar with the stuff I write about here on The 1919 Review might suspect that I only enjoyed this show because it had two things I liked: class struggle and Irish stuff (‘Inis Dubh’ means ‘Black Island’). But if they hadn’t been there, I would still have enjoyed it: I read a lot of science fiction and fantasy, and I appreciate a punchy, well-crafted tale of sorcery and adventure with strong characters and a vulgar edge. Blood Origin is all that.

Review: The Pull of the Stars by Emma Donoghue

Emma Donoghue’s The Pull of the Stars begins like a movie sequence full of long tracking shots, following a nurse on her commute through the dark of early-morning Dublin streets in the autumn of 1918.

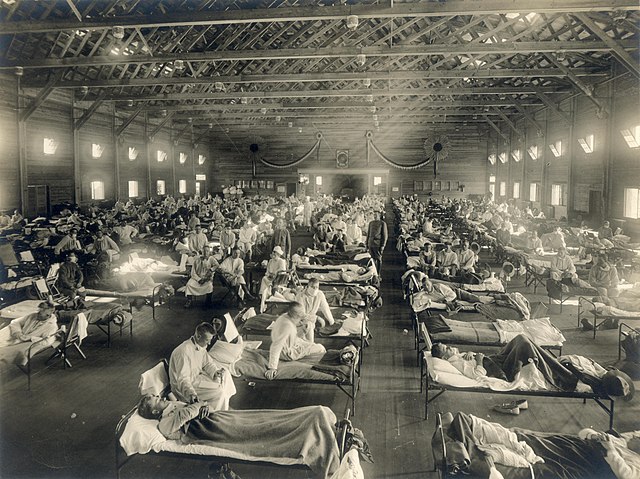

There are masked men spraying the gutters with disinfectant, children assembling at the train station for evacuation to the country, fear on the tram at every cough and spit: this is the height of the ‘Spanish Influenza’ pandemic.

After what she calls ‘the grippe,’ the next item in order of relevance to our narrator, Nurse Julia, is the ongoing First World War. It’s in its last few weeks, but she does not dare to hope that rumours of mutinies and moves toward peace are true. The war is as inescapable as the pandemic in the way it shows up in a wealth of details in this everyday experience.

The struggle for independence is a distant third, or perhaps it’s even further down the list of priorities for Julia. She passes the burnt-out ruins of O’Connell Street which still haven’t been rebuilt after the 1916 Easter Rising, which she dismisses in her mind as an act of crazy violence by a handful of extremists (Later she says to a rebel supporter, with icy understatement, ‘I got some experience with gunshot wounds during that week.’)

More relevant than the national question is the patriarchal influence of the Catholic Church: it is considered unseemly for Julia to cycle to the church-run hospital where she works.

It could be argued that the author is laying it on thick with the sheer amount of historically relevant things jostling for attention in every paragraph of Julia’s commute. But it’s authentic: these were extraordinary times and history was not something you could escape, least of all in the routine of everyday life. Reconstructing this extraordinary and forgotten moment is an important feat.

Later we will learn that Julia has never heard of Thomas Ashe, the Irish Republican who died on hunger strike in 1917. We never see her reading a newspaper, so it’s believable that the whole thing would have escaped her attention. And it’s not just plausible, it’s kind of refreshing. There was other stuff going on.

Getting caught up in the work

When Julia arrives at her hospital she and the reader get caught up in her work. Before you know it, you’re a third of the way through the book and you care deeply about the current condition of each of her patients. She’s looking after maternity patients who also have the virus; she has to keep these women and their babies alive. It’s one thing after another. We are swept up in the technical (and gruesome) details of the craft and the personalities which populate the cramped room.

When a volunteer arrived to help Julia, I was so invested in the work that I felt a rush of crazy gratitude toward this fictional character.

This character is Bridie Sweeney, and we will learn a lot about her over the next three days. And when we know Bridie’s story, we will question whether it’s enough for Julia simply to save the lives of these women and their infants. Many of them are destined for the orphanages, laundries, mother and baby homes andindustrial schools, a vast half-hidden Gulag which Bridie refers to as ‘The Pipe.’ Meanwhile infants in Dublin have a worse chance of surviving than soldiers in the battles of the ongoing war.

Changing attitude to the rebels

There is the gradual intrusion of Dr Kathleen Lynn, a real-life character. She is at first a troubling rumour – the hospital is scraping the bottom of the barrel and hiring a terrorist! – then a reassuring, compassionate and professional presence in the makeshift maternity/fever ward. We can see Julia, not consciously but no less obviously, changing in her attitude toward Lynn and the other ‘terrorists’ who led the 1916 Rising. People are dying every day anyway, argues Lynn – not from gunshot wounds, but from poverty and squalor caused by capitalism.

Lynn is perhaps a too-perfect character, who always has a clever and compassionate answer to every challenge. But it’s not like she’s Pearse or Connolly; she’s an underrated figure and long overdue a tribute in fiction.

A Covid novel

Like Oisín Fagan’s Nobber, The Pull of the Stars is a book about a past pandemic which was written just before Covid. The writer was not thinking of lockdowns, masks, jabs and Zoom calls. But the mind of the reader is dominated by comparisons.

What we see in the book is a lot worse than what Irish people have gone through in recent years, for the simple reason that in 1918-1919 there were apparently no half-way serious public health measures. There was no vaccine. Bad and all as our health service is today, there was no health system worthy of the name in 1918.

The attitude of the state is conveyed in poster slogans. One says: ‘Would they be dead if they’d stayed in bed?’ As Julia notes, it’s much more difficult for working-class people to stay in bed for days. Another says that ‘THE GENERAL WEAKENING OF NERVE-POWER KNOWN AS WAR-WEARINESS HAS OPENED THE DOOR TO CONTAGION. DEFEATISTS ARE THE ALLIES OF DISEASE.’

But there was always a strong element of that in public health messaging during Covid as well – scolding people instead of helping them, demanding sacrifices instead of providing basic supports. The hospital in The Pull of the Stars– overcrowded, understaffed; every nook and cranny turned into a ward, the canteen banished to the basement – will be drearily familiar to many who worked during Covid.

Midwifery

Earlier I said the opening was cinematic, but later on The Pull of the Stars reminds us what movies can’t do but novels can. It is unflinching in its treatment of the details of nursing and midwifery – there is no misguided delicacy, in other words. You won’t see this in Call the Midwife or Emma Willis: Delivering Babies. TV won’t show this stuff, and actually it couldn’t even if it tried.

I don’t know enough about the history of obstetrics to say how accurate it all is, but nothing rang false to me.

Changes

Equally convincing is the way Julia changes. The extreme circumstances, along with a whirlwind experience of love and loss, move her deeply. Lynn’s socialist politics appear to have a catalysing effect. At the end of the novel Julia makes a radical decision which puts her on a collision course with the nuns.

The real reckoning in the novel is not with the pandemic. The ‘Spanish’ Flu merely shines a revealing light on empire, patriarchy, capitalism and the church. Above all else, it’s the horrors of ‘The Pipe’ that bring about change in Julia’s character. I’d bet that the Tuam Babies scandal was closer to the mind of the writer than the Bird Flu or SARS.

There is some implausibility in the ending. But Donoghue has succeeded in convincing us that this was a historical moment rich in implausibility. This is a rich and strange and terrible time when people might do extraordinary things. The choice Julia makes is moreover justified on a thematic and story level – a miracle that is ‘earned’ by tragic losses earlier.

This is a short novel and, I found, a gripping one. I’m interested in this period in history so I drank in all the detail. More importantly, Donoghue’s narrative of a midwife caring for a handful of pregnant invalids is somehow more exciting than any epic action scene I’ve read lately.

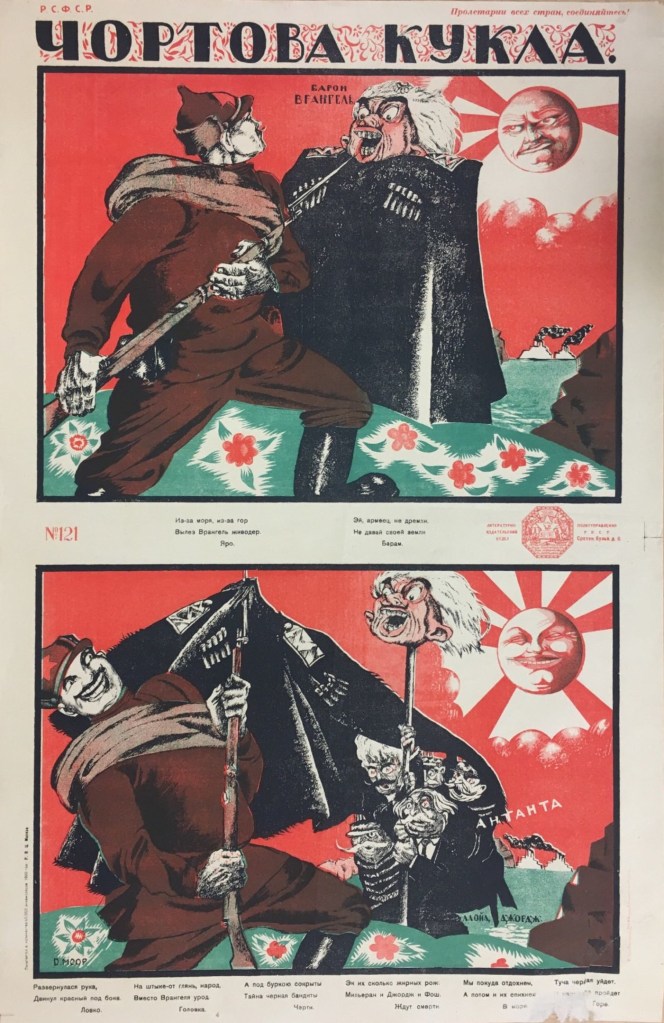

20: The Battle of Petrograd

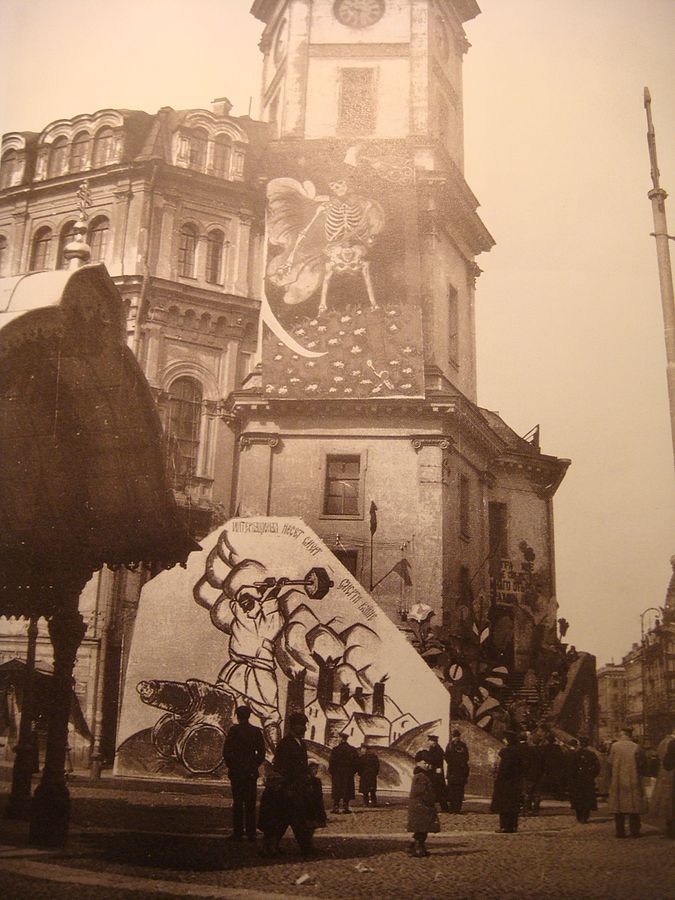

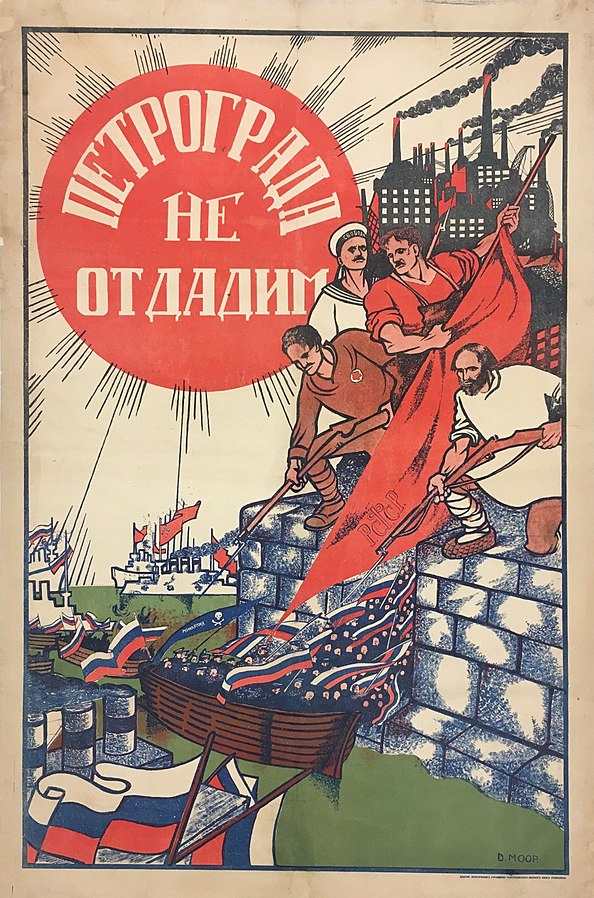

At the climax of the Civil War, a White Army made a bold attack on Petrograd, the city whose working population and garrison had made the October Revolution almost exactly two years earlier.

The city was no longer called Saint Petersburg, and not yet Leningrad – as if to remind us that the Civil War-era Bolshevik regime was something separate not only from Tsarism but from Stalinism. But even within that era, Petrograd in 1917 and in 1919 were two different cities. Petrograd in 1917 was inhabited by over two million people; the city of 1919 had a population of 600-700,000. One was an industrial giant, the other had a skyline of idle chimneys rising into cold smokeless air. Petrograd in 1917 was already a city of bread lines and food riots; by 1919, cut off from the places that had for hundreds of years supplied it with food and fuel, it was barely surviving on public canteens, the spoils of requisitioning squads, rations, and the black market. It was a starved, brutalized and cynical city.

Two years after the Revolution, did the popular masses of Petrograd still have the ability, or even the desire, to fight for it? The answer to that question will represent a judgement on the Soviet state and the Red Army.

Iudenich

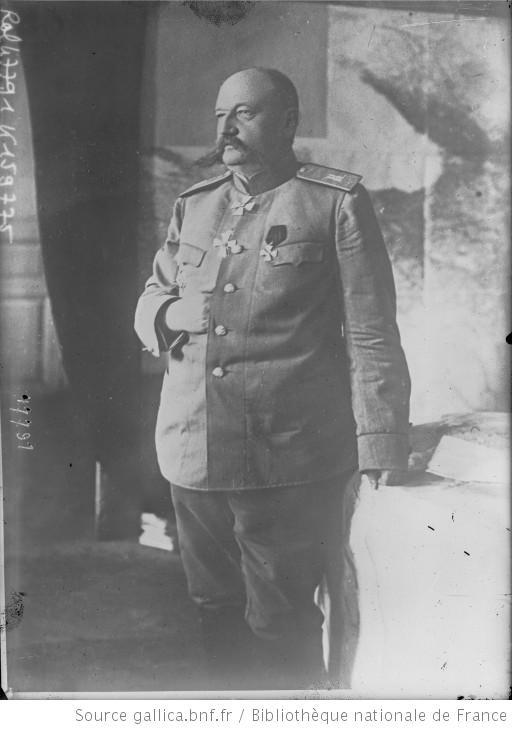

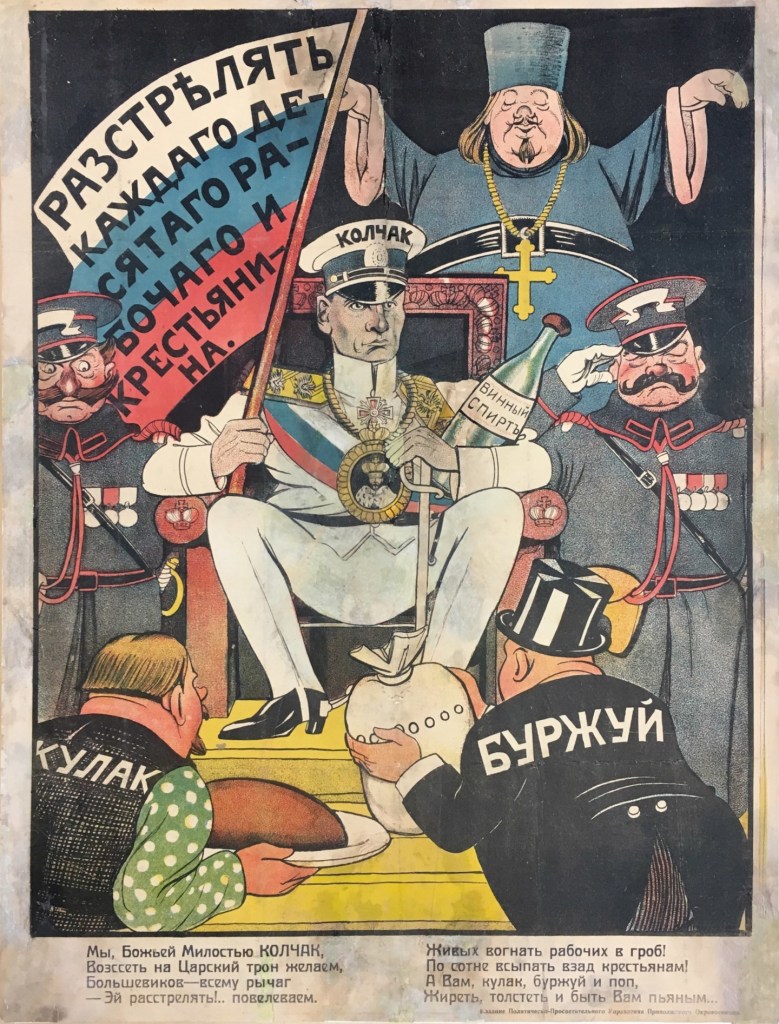

If you’ve read John Reed’s book Ten Days that Shook the World, you will know that a force of Cossacks tried to seize Petrograd in the days following the October Revolution. This was a force of just 700. The attacker in 1919 was a White Army of tens of thousands, led by the war hero General Iudenich.

Right on the doorstep of Petrograd lay the Baltic States, which, first under German occupation and then under British clientship, had served as an incubator for White armies. One White army which mustered in Estonia became known as the North-West Army, an aggregation of officers and reactionaries who swore allegiance to the Tsar. Admiral Kolchak, reigning as Supreme Leader of the White armies in distant Omsk, appointed General Iudenich to command this Baltic army in mid-1919.

Iudenich had conquered a supposedly impregnable mountain fortress from the Turks in the First World War. He had served in the anti-Soviet underground in Petrograd; one wonders how this was feasible given his fame and distinctive appearance (he was a large man with long tusk-like moustaches). He had fled Petrograd in late 1918. Then for the first few months of his command he lived in a hotel in Helsinki with what we can charitably call a government-in-exile – the oil baron Lazonov held three different portfolios, and the ministers were more rivals than colleagues.[i]

Soon after he assumed command, in May 1919, his North-West Army made an initial assault on Soviet territory. There was a spasm of fear in Petrograd. But Iudenich contented himself, for now, with conquering Ingermanland, a sliver of the Russian-Estonian border area.

We learned very little about the Russian Civil War in school, but we did memorise the names of the three White generals – Kolchak, Denikin and Iudenich. The army under Iudenich was not in the same league as the other two – 20,000 fighters to their (roughly) 100,000 each. This was because he had no Cossacks in his neighbourhood and no large population from which to recruit. On the other hand, he had some distinct advantages. The Estonian border is only 130 kilometres from St Petersburg (Dublin to Enniskillen, or London to Coventry) – there were no vast Russian expanses between him and his objective. Of all the White armies his had the shortest lines of supply and communication with the Allies; British naval forces controlled the Baltic and could slip vessels right into Kronstadt harbour. Lastly, if he played his cards right, Iudenich might be able to bring in two neighbouring states on his side.

How to Lose Finns and Alienate Estonians

The Whites and the Finnish and Estonian governments were common enemies of the Soviet regime. Between them, Finland and Estonia could send enough soldiers into Russia to boost Iudenich’s numbers up from 20,000 to 100,000. But the national question was a massive weak spot for the White Russians. They often enraged their potential allies. In Autumn 1919 they would appoint a ‘Governor’ of the Estonian capital city – a city over which they had no control anyway. Iudenich insisted: ‘There is no Estonia. It is a piece of Russian soil, a Russian province. The Estonian government is a gang of criminals who have seized power, and I will enter into no conversations with it.’[ii]

The British mikitary tried to get them to make friends. Brigadier-General Marsh threatened Iudenich: ‘We will throw you aside. We have another commander-in-chief all ready.’

On another occasion Marsh, in person, issued an ultimatum to a gathering of White Russians. He declared that they had 40 minutes to form a democratic government which recognized Finland.[iii] Such measures usually don’t work for parents or teachers (‘I’m going to count to three! One…’) and they didn’t work for a Brigadier-General either. But they show the role which Britain took on itself.

British officers were match-makers, kingmakers, fixers, naval support, and a source of massive supplies of arms and uniforms. They operated a veritable taxi service across the Baltic for various anti-communists to meet up and try to overcome their differences. In spite of everything, Estonia ended up joining the attack on Petrograd – a degree of cooperation which surely would have been impossible without patient British intervention.

Things were no better as regards Finland. In summer 1919 the Finnish government offered the Whites an alliance in exchange for some small territory in Karelia. Iudenich’s superior Kolchak reacted with the words: ‘Fantastic. One would suppose Finland had conquered Russia.’[iv]

In late 1918 and early 1919 the Soviet government supported Estonian and Lithuanian socialists in a series of wars against the British-backed nationalist regimes. But by summer, the Reds had recognised that the potential for a Soviet Baltic was lost for the near future, and they were willing to make a deal with the governments of the Baltic States. For example, on August 8th they offered to recognize Estonia in exchange for the town of Pskov.

Operation White Sword

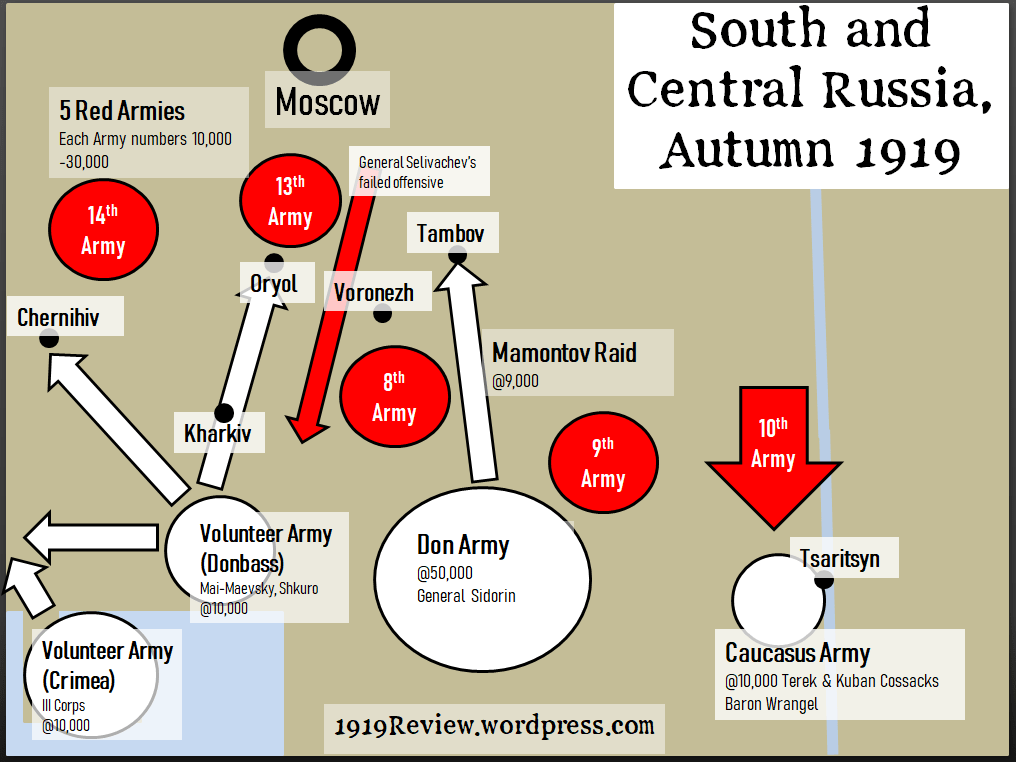

In summer 1919, General Denikin’s forces conquered southern Russia and swathes of Ukraine, then in the autumn surged north toward Moscow. These victories told Iudenich it was time to make his long-awaited move on Petrograd.[v]

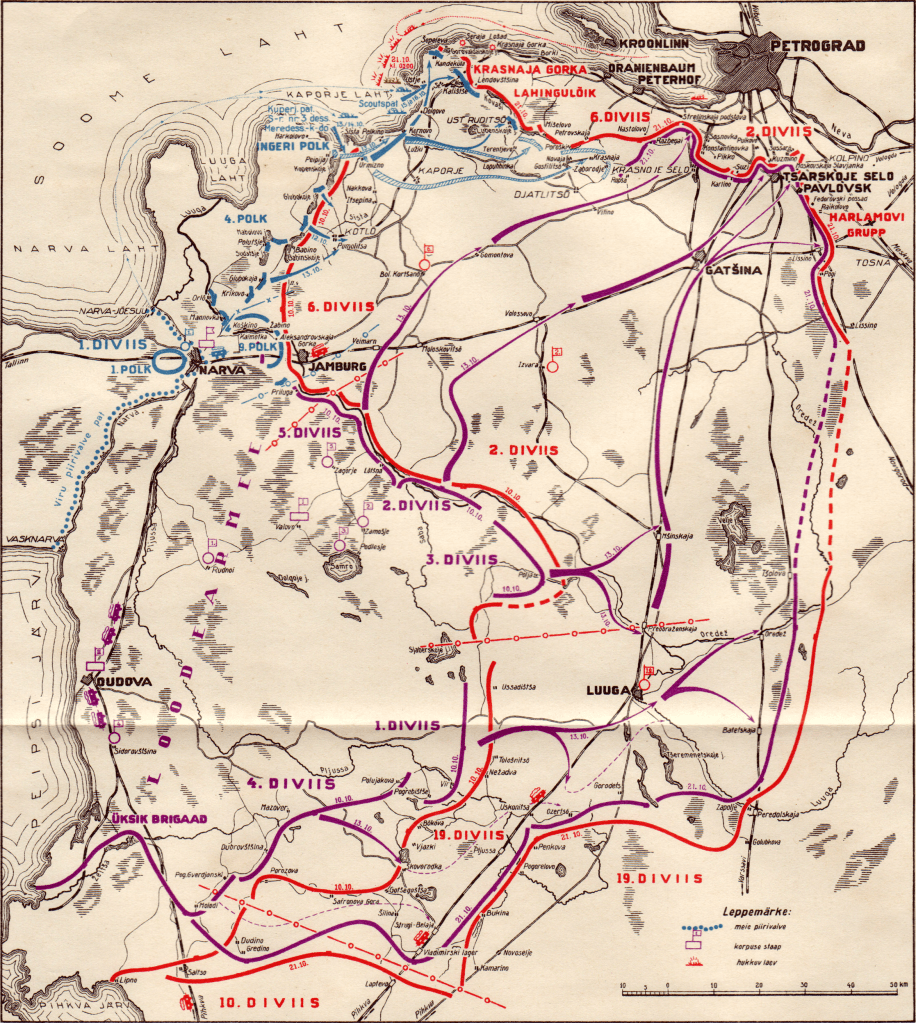

From July British aid began to pour into the hands of Iudenich. And on October 12th, North-West Army began Operation White Sword, a two-pronged advance toward Petrograd. Meanwhile the Estonian Army attacked along the coast and laid siege to the fortress of Krasnaya Gorka. There were 50,000 soldiers in the White Army, with 700 cavalry, four armoured trains, six planes and six tanks.

White Armies always exhibit interesting disproportions, and this one was no exception: one in ten of the 18,500 combat troops were officers, and there were nearly as many generals (53) as there were artillery pieces (57).[vi]

Against this, the Reds were in disarray. Their Baltic Fleet was bottled up in Kronstadt Harbour by the British fleet. The approaches to Petrograd were held by the Red 7th Army. Its 40,000 personnel were not all armed, and had been mostly idle for months. The defeat in Estonia early in the year; the transfer of the best elements to other fronts; and the Liundqvist Affair, in which one of the top officers turned out to be a White spy, all sapped morale. With the onset of the offensive, despair and panic broke out amid the frontline soldiers and soon took hold in Petrograd. 7th Army’s soldiers ran away, dropping their weapons. An entire regiment went over to the Whites.

So great were the early failures of Red Seventh Army that leaders on both sides almost took for granted the fall of Petrograd. The newspapers in the west spent the week reporting that it was imminent. They were not delusionary: in Moscow on October 15th Lenin spoke in favour of surrendering the city. It would be a temporary concession, he argued: the city was home to countless thousands of communists, each one a potential insurgent; let the Whites rest upon it as on a bed of nails.

In early October the pressure on the Southern Front was intense. Whether to defend Petrograd or to let it fall was a decision which, in the words of the Red commander Kamenev, ‘burned in my brain.’ If reinforcements were sent to Petrograd, would there be enough to defend Moscow?

But Trotsky and Stalin both protested against the idea of surrender. Lenin relented, and Stalin took over command of the Southern Front while Trotsky and his armoured train took off for Petrograd.

Trotsky’s Armoured Train

The rail line from Moscow to Petrograd was in danger of being cut off by the inland prong of Iudenich’s advance. So for Trotsky and his staff it must have been an anxious journey.

This was the same train on which the war commissar had arrived at Kazan in August 1918. In the intervening year it had been encased in armour and given three back-up locomotives. Wherever it went, even when it passed a small village, flyers and newspapers rolled off its printing press and Trotsky himself would give a speech. ‘Workers and peasants who listened to him were frequently entranced.’ By the end of 1918 the train had over 300 personnel – it was ‘a full military-political organization.’[vii] It initiated changes at the front, tied the front to the rear and delivered the ‘ideological cement’ which held together the Red Army.[viii]

By war’s end it had visited every front and covered 120,000 kilometres on 36 trips, had been in battle thirteen times and suffered 30 casualties. After the war, the train itself was awarded the Order of the Red Banner [ix] – a whimsical notion, like something out of Thomas the Tank Engine.

The Stone Labyrinth

The arrival of Trotsky in Petrograd had an electrifying effect, by all accounts (including his own). Trotsky and his staff shook up the demoralised local officials by force of argument and, where deemed necessary, by sacking and replacing people. The mood changed in the city overnight as the population saw stern measures being taken first of all at the top, while food rations were doubled.

A plan was drawn up to turn the city into a fortress. Trotsky said that it was better if the Whites were defeated outside the city because ‘Street battles do, of course, entail the risk of accidental victims and the destruction of cultural treasures.’[x] But if that should fail, he was prepared for urban warfare in a plan that anticipated Stalingrad. The army of Iudenich would be lost and ground down in the ‘stone labyrinth’ [xi] of hostile streets.

Trotsky was able to mobilise the population to dig trenches, to barricade the streets, and to search, house by house, for White agents. His memoir captures the mood:

The workers of Petrograd looked badly then; their faces were gray from under nourishment; their clothes were in tatters; their shoes, sometimes not even mates, were gaping with holes.

“We will not give up Petrograd, comrades!”

“No.” The eyes of the women burned with especial fervor. Mothers, wives, daughters, were loath to abandon their dingy but warm nests. “No, we won’t give it up,” the high-pitched voices of the women cried in answer, and they grasped their spades like rifles. Not a few of them actually armed themselves with rifles or took their places at the machine-guns.Detachments of men and women, with trenching-tools on their shoulders, filed out of the mills and factories. The workers of Petrograd looked badly then; their faces were gray from under nourishment; their clothes were in tatters; their shoes, sometimes not even mates, were gaping with holes.

“We will not give up Petrograd, comrades!”

“No.” The eyes of the women burned with especial fervor. Mothers, wives, daughters, were loath to abandon their dingy but warm nests. “No, we won’t give it up,” the high-pitched voices of the women cried in answer, and they grasped their spades like rifles. Not a few of them actually armed themselves with rifles or took their places at the machine-guns.

The Bashkirs

Alongside these traditional supporters, Petrograd hosted new and improbable allies. The Bashkir cavalry, the Muslim nomads who had come over to the Reds back in February, happened to be on a visit to the city. We find this description in a novel written by an eyewitness:

They seemed to be happy riding through a town where the horses’ shoes never struck the soil, where all the houses were made of stone… but which was unfortunately lacking in horse troughs. And life must be sad there since there are neither beehives, nor flocks, nor horizons of plains and mountains… their sabres were bedecked with red ribbons. They punctuated their guttural singing with whistle blasts … Kirim always wore a green skullcap embroidered in gold with Arabic letters, even under his huge sheepskin hat. This man was learned in the Koran, Tibetan medicine, and the witchcraft of shamans … He also knew passages of the Communist Manifesto by heart.[xii]

According to western newspapers, pecking at crumbs of rumours in Helsinki, the Bashkirs brought with them a new strain of typhus. Not improbable; the country was riddled with it. Nor is it improbable that this was a racist myth.

The Bashkirs caused a stir in Helsinki for other reasons too. Finland had 25,000 troops facing Petrograd, threatening the prospect of a second front. It must have been a tempting prospect for the White Finns: if they helped take Petrograd they could hold onto some of the territory they would grab in the process. But the White Russians alienated them, and the war hawk Mannerheim was out of power, and there was an anti-war mood among the public. Trotsky had, since September 1st, been making the most of these factors by alternating generous peace proposals with dire threats. In response to any Finnish invasion, he said, the Soviets would unleash a horde of Bashkirs to ‘exterminate’ the bourgeoisie of Finland.[xiii]

The First Soviet Tanks

The Whites made rapid progress toward the city. Early in the campaign the Reds were outnumbered. But throughout the campaign, even later when the scales shifted, the White Guards punched above their weight. They would sneak around Red positions, open fire at them from multiple directions, and set off a stampede of red-star caps and bogatyrkas in the direction of Petrograd.

As at Tsaritsyn, the Whites had only six British tanks. In such small numbers and in this mode of warfare they were of little practical use. But the sight of the crushing treads of these bullet-proof killing machines, or even the rumour of them, terrified the Red soldiers.

In response, the steelworks of Petrograd began to produce the first Soviet tanks. These were not marvels of engineering. Different accounts describe them as almost static, or as tactically useless. But they proved to be a psychological antidote to a psychological threat. The sight of Red ‘tanks’ rolling out of the Putilov works or taking their places in the defensive lines was a source of great encouragement to the Red fighters, who made cheerful puns playing the word ‘Tanka’ and the name ‘Tanya’ against each other.

Seventh Army was heartened by all these changes. ‘The rank-and-file of the Red army got some heartier food, changed their linen and boots, listened to a speech or two, pulled themselves together, and became quite different men,’ writes Trotsky. The Mensheviks put aside their differences with the Bolsheviks and rallied to the defence of the city.

Meanwhile ‘field tribunals did their gruesome work.’[xiv] White organizations – the National Centre and the Union for the Regeneration of Russia – operated underground in the city and the Cheka worked to root them out. Notices would appear bearing lists of ‘COUNTER-REVOLUTIONARIES, SPIES, AND CRIMINALS SHOT.’[xv] The judgments of the Cheka were quick and ruthless.

Could Iudenich take Petrograd?

The historian Mawdsley dismisses the threat posed by Iudenich on the basis that his army was relatively small. Trotsky agreed. In his view, even if the Whites took the city, they would not be able to hold it or to build on their success.

There are grounds to disagree with both Mawdsley and Trotsky on this. In this war, numbers counted for less than morale. In the Caucasus, 20,000 Whites had defeated 150,000 Reds. If panic had been allowed to continue in Petrograd, even a large army would have been unable to hold it.

If Petrograd fell it would later be recaptured, all things being equal. But how could all things possibly stay equal if Petrograd fell? We must consider the moral effect on Red and White soldiers, and beyond Russia. Among the Allies it would give a tremendous boost to the hawks like Churchill. The Finnish government might open a second front, and the Estonian government might commit fully to the war. A White Petrograd would be as open to British shipping as Tallinn or Helsinki. Military and economic aid could pour in just as it had poured into Tallinn.

But the prospect of a White victory was made dimmer by discord behind the lines. In Latvia, a rival White Russian general thought this would be a great moment to try and conquer Riga, the Latvian capital. Not only did this distract the British and the Estonians; the resulting in-fighting, from October 8th, guaranteed that there would be no attack on Russia from the Latvian border, so the entire 15th Red Army, which had been stationed there, now began a slow advance north to join the battle for Petrograd.

The White commanders often let their personal pride get in the way of success. The Latvian diversion is one example; another came when a division commander ignored orders to cut the Moscow-Petrograd railway line because he wanted to be the first into Petrograd.[xvi] This allowed reinforcements from Moscow to bolster the defence.

The Commissar for War Saddles Up

The White advance continued in spite of these challenges. Away in England, Churchill was confident of success, promising a massive consignment of equipment, enough for Iudenich to equip a whole new army, and predicting that there would be ‘lamentable reprisals’ – White Terror – when the city fell.[xvii]

The Reds did not have a cordon or a trench line in front of the city. They had concentrated striking groups which, in theory, were supposed to pounce on less numerous White detachments. But the Reds were on edge. Gatchina was lost on October 17th when some Red cadets came under impressive volleys of fire, took fright, and fled. It turned out to be the work of a single enemy company hiding in the town’s park.

Just the next day Trotsky happened to be in the division headquarters at Aleksandrovsk when a mob of Red soldiers came hurrying past. Winded and panic-stricken men halted to report that an enemy force had appeared on their flank, so they had briefly opened fire then retreated ten kilometres.

The officers at division headquarters consulted their maps and informed the fleeing soldiers that the ‘enemy force’ was actually a Red column. The commander of the fleeing soldiers must have flushed with shame. His battalion had shot at their own friends then fled in terror, leaving a gap which the Whites, at this moment, would be exploiting.

Trotsky took hold of the nearest horse and mounted it in the midst of the hundreds of frightened soldiers. They were at first confused by the spectacle of the war commissar riding around issuing orders to them directly, face to face. They watched him chase down, one by one, all those soldiers who were still retreating, and with stern commands prevail on them to turn around.

A voice was yelling, ‘Courage, boys, Comrade Trotsky is leading you.’

It was Trotsky’s orderly Kozlov, an old soldier from a village in Moscow province. He was running around after Trotsky, waving a revolver in the air and repeating his commands. To a man, the battalion advanced with the war commissar mounted in their midst. After two kilometres, writes Trotsky, ‘the bullets began their sweetish, nauseating whistling, and the first wounded began to drop.’ They did not slacken their pace, but ran quick enough to break a sweat in the late October chill.

Combat was joined. The regimental commander who had taken fright at a friendly unit was, it appears, eager to redeem himself. He went fearlessly into the line of fire and was wounded in both legs. The battalion advanced the remaining eight kilometres under fire until the position it had fled from was ‘thus retaken by some brawny lads from Kaluga, where they drawl their a’s,’ and Trotsky returned to HQ on a lorry, which picked up the wounded as it went.

Serge imagines the War Commissar as, seated in the truck, he ‘wiped the sweat off his brow. Ouf! He had almost lost his pince-nez.’[xviii]

But in spite of feats like this, the frontlines closed in on the outskirts of the city. The Whites could see in the distance the sunlight on the golden dome of St Isaac’s cathedral in the middle of Petrograd, and they boasted that they would be marching down the Nevsky Prospekt in the coming days.

But as the fighting came closer and closer to Petrograd, the resistance grew tougher. At the Pulkovo Heights south of town the Red frontline at last began to hold. The British had sunk the warship Sevastopol in a raid on Kronstadt Harbour months before; somehow the Reds raised it up and restored its guns to working order. Along with all the naval artillery concentrated in Kronstadt, the guns of the Sevastopol pointed inland and let loose terrible volleys on the Whites.

Cadets from the training schools were rushed to the frontlines. The coastal fort of Krasnaya Gorka had defeated the Estonian advance along the shore, so 11,000 Kronstadt sailors were freed up to join the defense of Petrograd.[xix]

Pulkovo Heights

The Whites were given an order to capture the Pulkovo Heights, a rise just south of the city, on the night of October 20th-21st. But at 11pm the Reds went on the attack, jumping the gun. High-explosive shells manufactured in Britain or France exploded over the heads of Bashkir cavalry, of young peasant conscripts in khaki, of sailors in black. The sailors and worker-volunteers ‘fought like lions.’ They charged at tanks with bayonets and revolvers.[xx] The attackers took heart when the makeshift Red tanks joined the battle: ‘The Red troops greeted with delight the appearance of the first armoured caterpillar.’[xxi]

The Whites were at the end of their supply lines and, in the words of Isaac Deutscher, the power of the Red Army was like a compressed spring ready for the recoil.[xxii] The Reds no longer had any space behind them into which to retreat. Supplies and communications, for once, ran smoothly thanks to the proximity of Petrograd and its supplies, infrastructure and volunteers. But the Whites were determined and brave, and Iudenich brought up reserves to bolster them. On October 22nd the Whites held firm in a day of terrible fighting.

The Reds now had a massive superiority in numbers. Morale was transformed from a few days before: units tried to out-perform one another. The sailors were ‘splendid’ because they knew the Whites would take no prisoners from among them.[xxiii] Trotsky’s train crew was in the thick of the fighting in these days: three were killed, six wounded, and three shell-shocked.

On October 23rd the Reds recaptured the key suburb of Tsarskoe Selo. Meanwhile 15th Army – the army which had been freed from the Latvian border thanks to White in-fighting – was advancing slowly into the deep rear of the Whites. White soldiers began surrendering by the dozen.

Red Initiative

The Whites began a fighting retreat, and the Red Army pursued.

Trotsky’s orders contained humanistic messages. Enemies who surrendered must be spared – ‘woe to the unworthy soldier’ who hurts a prisoner. ‘Only a tiny minority’ of the Whites, both officers and enlisted soldiers, are determined enemies, argued an order of October 24th. On the same day, an order urged ‘Red warriors’ to draw a distinction between the British government and the British working people.[xxiv] A later order (No 164) says that peasants conscripted by the enemy will be paid, given horses and allowed to keep their uniforms if only they hand over their rifles.

Draconian tones reassert themselves in italics in an order of October 30th (No 163), a sign that the White retreat was a controlled one and that the fighting was still formidable: ‘anyone who tries to start a panic, calling on our men to throw down their arms and go over to the Whites, is to be killed on the spot.’

Iudenich fought hard until November 3rd, then began a general retreat toward the Estonian border. Trotsky was for sending the Red Army after them into Estonia. But Chicherin and Lenin argued against this, and prevailed.

When the forces of Iudenich reached the border, the Estonians first denied them entry then let them in, disarming and imprisoning them. The White army was already afflicted by typhus, and in prison conditions it only got worse. The Estonian government fed them only on lampreys and forced them to cut down trees through the Baltic winter. It is estimated that 10,000 perished [xxv] – if so, the Estonians killed more of them than the Reds.

Before the end of the year, Estonia and Soviet Russia had signed an armistice, and a peace treaty soon followed. Over the next year the Soviet Union sealed peace treaties with Latvia and Lithuania as well.

The Battle of Petrograd was a judgment on two years of Soviet power. Looking at the depressed and almost lifeless city in autumn 1919, you’d be forgiven for thinking that there was nothing left of the spirit of revolution. But thousands of the city’s workers fought or participated in the battle. Early on, the Red Army was prone to humiliating attacks of panic – but strong leadership, tight supply lines and an urgent threat brought out its strengths in the end, and once the initiative passed to their side these strengths proved overwhelming.

In this post we have seen the working class of the young Soviet Republic and its army tested on the relatively small scale of one city. During those weeks, Central Russia went through a trial that was bigger in scale to the point where it was qualitatively different. That will be the subject of the next episode – the final chapter of this second series of Revolution Under Siege and the decisive chapter of the whole story.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

Memoirs of Trotsky: https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1930/mylife/ch35.htm#:~:text=%E2%80%9CTo%20defend%20Petrograd%20to%20the,extinction%20if%20it%20met%20serious

[i] Smele, Jonathan, The ‘Russian’ Civil Wars, Hurst & Company, London, 2015, p 128

[ii] Kinvig, Clifford, Churchill’s Crusade, Hambledon, 2006, p 272

[iii] Kinvig, 275-6

[iv] Kinvig, 273

[v] Churchill believed that Iudenich could take Petrograd, so much so that he had moved on to second-order concerns: earlier in the year he had communicated to Iudenich his concern that the conquest of Petrograd would turn into one massive pogrom: ‘Excesses by anti-Bolsheviks if they are victorious will alienate sympathy British nation [sic] and render continuance of support most difficult’ (Kinvig, 274)

[vi] Smele, 129

[vii] Service, Robert, Trotsky, Belknap Press, 2009, p 230-231

[viii] Smele, 132

[ix] Smele, 132,3

[x] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, ‘Petrograd Will Defend Itself From Within As Well’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch135.htm

[xi] Mawdsley, p 276

[xii] Serge, Victor, Conquered City, 1932, trans Richard Greeman, New York Review of Books, 2011, p 169-170

[xiii] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch134.htm

[xiv] Kinvig, p 284

[xv] Serge, Conquered City, p 189

[xvi] Beevor, Antony, Russia, Orion, 2023, p 365

[xvii] Beevor, 366

[xviii] Serge, Conquered City, p 186

[xix] Serge, Conquered City, p 124

[xx] By some accounts the tanks were not present at this decisive struggle.

[xxi] Trotsky, How the Revolution Armed, ‘The Turning Point’ https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1919/military/ch141.htm

[xxii] Deutscher, The Prophet Armed, 1954, Verso Books, 2003, 365

[xxiii] Serge, Conquered City, 185-6

[xxiv] The Soviet Union had suffered thousands of deaths from the weapons of the British navy and millions of deaths from a British blockade, and was at that moment fighting against three armies in British uniforms and with British rifles, and furthermore had, on the night of October 21st, lost three destroyers with all hands to British mines; but Order No. 159 ended with the words: ‘Death to the vultures of imperialism! Long live workers’ Britain, the Britain of Labour, of the people!’ All references to Volume II of How the Revolution Armed.

[xxv] Kinvig, 286

Ebb Tide of World Revolution (Premium)

The Russian Civil War was turning against the Reds in Russia at the end of the summer of 1919. In the East there were setbacks. In the South the situation was dire. From the West a White Army threatened Petrograd. Meanwhile the global revolutionary struggle was taking the same turn, only more sharply. That will be the focus of this post.

Become a paying supporter to get access

Access to this article is limited to paying supporters. If you already subscribe by email, thank you. But if you want to become a paying supporter, please hit ‘Subscribe’ below.

Donate less than the price of a coffee, and you can access everything on this blog for one year.

If you don’t feel like donating, most of my posts are still 100% free, so browse away, and thanks for visiting.

19: ‘To Moscow!’ (Premium)

This post is about the most decisive campaign of the Russian Civil War, in which the armies of Denikin swept toward Moscow. We will be following three White Armies on a front spanning the huge distance from Crimea to the Volga.

This is a lot to wrap our heads around, so let’s start smaller: with a single combatant in these operations. British support was a key factor in the campaign we are about to describe. So let’s focus on a British officer.

The man who took Tsaritsyn

When in 1921 Major Ewen Cameron Bruce was jailed and stripped of his medals, it was the shabby end of a stunning career in the service of the British state…

Become a paying supporter to get access

Access to this article is limited to paying supporters. If you already subscribe by email, thank you. But if you want to become a paying supporter, please hit ‘Subscribe’ below.

Donate less than the price of a coffee, and you can access everything on this blog for one year.

If you don’t feel like donating, most of my posts are still 100% free, so browse away, and thanks for visiting.

Appendix: The Diary of a White General

While working on my ongoing series Revolution Under Siege, I was happy to come across a great primary source: the 1919 diary of the White Russian General Alexei Pavlovich Budberg.[i] I found it not only informative, but compelling and even moving. It should be released as a Penguin Modern Classic, or Vintage, or Oxford, or one of those. It’s literature.

Budberg was a middle-aged officer of the old army who served the Siberian White regime of Admiral Kolchak as War Minister during 1919.

The diaries he kept during that time are full of sharp ironies and deep conflicts. Budberg is fighting for a bourgeois Russia but he loathes the bourgeoisie and thinks little of his fellow Russians. He hates the Reds viscerally, but he continually voices his grudging professional respect (‘How I envy the Reds now! No matter how vile they are, decisive people are at the head of their army’). He is annoyed at Allied demands and importunacy – but without them, he would have no rifles or boots for his men. He is in favour of a more centralised and out-and-out dictatorship – but it is clear to the reader that the White regime is organically composed of vested interests which will not tolerate such discipline, and indeed our narrator is outraged when his friend is arrested for corruption.

The reader respects Budberg, because he is so frequently correct in his dire predictions. At one stage Budberg hears his colleagues boast of how they rejected Finnish offers of an alliance against the Reds. They are proud that they refused to consider any territorial concessions, even in exchange for an alliance which might well deliver St Petersburg into White hands. Budberg says loudly: ‘What horror and what idiocy,’ which occasions looks of astonishment from those around him. But history has vindicated what he said.

At the same time I found him far from sympathetic. His contempt for Russians comes across in an anecdote he relates:

all the efforts of the railway militiamen to remove from the rails the crowd of peasants and passengers sitting on them were unsuccessful; but when three Czechs appeared and, shouting “let’s go,” began to beat the Russian citizens with butts, the platform and the rails were empty, and the “masters of the Russian land” decorously lined up behind the line assigned to them by the Czechs.

He comments that ‘the Russian crowd needs a stick… of foreign origin.’ This comes from ‘the habit of being under a Tatar[…] a German, and more recently a Jew.’

Like most Whites, Budberg believes that the Revolution and Bolshevism are part of a Jewish conspiracy. This belief resulted in the deaths of thousands of Jewish people during the civil war.

His only problem with the coup d’etat by which Kolchak came to power in November 1918 was that it promoted some unqualified people. He has no regrets about suppressing the SRs.

Prophet of Doom

Meanwhile his diary provides valuable evidence as to the weaknesses and crimes of White Siberia. This is all the more impressive because he is not writing in hindsight but in real time.

Budberg is frustrated with critics and talkers – for example, the ladies who draw his attention to problems in the hospitals, but will not volunteer as nurses, or even donate linen. Some concerned citizens demand that schools be built for the children. Budberg puts them on the spot by guaranteeing them money, transport and all the materials they need. But no work is done. His comment is scathing: ‘They are intellectuals, and teachers, and democrats, and accusers, and intercessors, but they are not so stupid as to try to build those buildings that will deprive them of continuing to do nothing.’

Something as simple as providing care to the wounded is hampered by corruption and profiteering and bureaucratic haughtiness. Wounded soldiers arriving late were left all night without blankets, because certain underlings did not want to disturb the sleep of the person responsible for issuing said blankets.

The entry of the Siberian Cossacks into the war is greeted with enthusiasm by all and sundry in Omsk, with Budberg appearing to be the sole exception. Sure enough, he is soon proved right: the Cossacks empty the state warehouses, issue five uniforms to each man; the atamans deliver funds and loot to the villages that voted for them; and when the time comes to fight they are brave but undisciplined. Their attack fails. All they have achieved is to drag the Whites into yet another failed and costly offensive.

A lot of the texture of daily life in White Siberia seems to have revolved around disputes over trains. Usually these were disputes between groups of different nationalities. A whole catalogue of such could be gleaned from Budberg’s bitter writings, but the Czechs are the ones he resents the most. This is another bitter irony, as he is forced into an attitude of grudging respect for the Czech commander Gajda who levels valid criticisms at Kolchak.

There are constant ambitious reforms and overhauls of systems – which will be familiar to workers today in the corporate world or in government departments. The result is a landfill of broken systems, with the real problem never addressed: the lack of qualified people.

He identifies the Reds with senseless and brutal violence. However he is well aware of White Terror and provides insights into its nature: punitive detachments are sent out without training or resources, and quickly resort to indiscriminate violence. Here as in government departments, the key problem in his eyes is lack of qualified people. Everywhere, he comes to realise, military warlords have become used to operating with impunity, and this has gone too far to be contained. These ‘hyenas’ cannot now be tamed. Warlordism, he predicts, ‘will probably eat us, but it itself must perish among the stench it produces.’

Budberg hates General Ivanov-Rinov, who is in his eyes not a military specialist but a mere ‘police bloodhound.’ He relates that Ivanov-Rinov’s wish-list includes kill quotas and the power to shoot all deserters and speculators. We wonder at what point Budberg will realise that the Whites are guilty of everything he accuses the Reds of.

Too far gone

All in all, it is a vivid portrait of a wretched government, of a train-wreck happening in slow motion from the point of view of one qualified to foresee the disaster but powerless to stop it. What he can’t see is that the reforms which he sees as necessary would tear the White movement apart. Challenging speculators, scammers and corrupt people is urgently ‘necessary’ – but he can’t see that the radical measures necessary to fight corruption would send shockwaves through the businesspeople and bureaucrats of Omsk. He is outraged by the warlordism and banditry he sees on his own side – but any real measures to tackle this would alienate necessary allies and even the rank-and-file.

He is more far-seeing than those around him, in a technical sense. He knows not only that a disaster is coming, but how and why it will unfold. We admire him as a protagonist because he knows his stuff and proactively identifies problems and tries his best to solve them. Most of those around him, meanwhile, seem complacent and cynical. In particular those around him greet each new offensive with enthusiasm. He sees that a defensive strategy would be far more effective, and in each case the specifics of his critique are proved right.

But is he really more far-seeing than those around him? The others, whose apparent complacency and amateurism enrage him so much, perhaps see further than him in a political and moral sense. They know their regime is riddled with rot, so badly riddled that it cannot be purged without destroying the whole organism. A defensive strategy makes more sense militarily. But what is there to defend? You are merely buying time for the rot to do its work. It’s too far gone already.

Their panacea: to take Moscow. If they can pull off this goal, they will have problems and resources on a different order of magnitude entirely, and the infantile disorders of the early Siberian days will be a thing of the past. All this explains why those around Budberg are on the one hand so cynical and selfish and on the other hand so eager to get excited about apparent miracles.

I think these considerations go a long way toward explaining the strange character of Admiral Kolchak. As I see it, he was just holding the line, waiting for a miracle: the collapse of the Reds; the victory of Denikin; a greater commitment from the Allies. Without such a miracle, victory for White Siberia was not possible, even if Budberg got his way.

Partisans, Frogs and Switchmen

In passing, Budberg tells extraordinary stories, like the tale of a Red partisan group which posed as a White detachment and endeavoured to capture Omsk. Their plan was rumbled by White counter-intelligence but before the Reds could be arrested off their trains, they took off into the wilderness with all the weaponry that had been issued to them. They formed a partisan force threateningly close to Omsk.

Images and turns of phrase which may well be commonplace in Russian strike my mind as powerful and fresh. For some reason, frogs are a recurring image. ‘The Omsk frogs continue to croak,’ he notes, and elsewhere he denounces the Semyonov regime as ‘the Chita swamp and its absurd frogs.’ The Omsk government departments, local in reality but with all the pomp of old Tsarist state organs, are ‘frogs swollen into an All-Russian Ox.’

(Update: a reader has helpfully pointed out that this is a reference to a classical fable – https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Frog_and_the_Ox)

China Miéville in his book October speculates on a strange phrase which occurs in the sources: leftist workers being denounced as ‘switchmen.’ He makes a good case for investing this with significance. The phrase occurs here, in the entry for July 30th. I can’t make out what it means in context but perhaps others can figure it out.

White and Red

It’s interesting to compare Budberg’s diary with Trotsky’s military writings. They faced the same problems: commanders sending in inflated reports, turning skirmishes and panics into great victories or crushing defeats, or soldiers carting along their entire households in long wagon-trains that straggle behind the army. They engaged in the same conflicts with their own respective colleagues: professionalism against guerilla-ism, military science against romantic notions glorifying the offensive.

But Budberg and Trotsky were at odds over the question of whether commanders should go into battle personally. For Budberg, it was stupid demagogy. For Trotsky, it could be necessary in order for the commander to earn his authority.

Capitalist White territory faces the same social and economic problems as Communist Red territory. There is a lack of machinery, of trained professionals and of capital for investment. This leads to bureaucracy, waste and a scarcity of consumer goods (mitigated by the flow of material from the Allies). We are taught in school that these were features of communism, ie, that they somehow resulted from too much sharing. In reality, they are problems of underdevelopment which we see in all countries of whatever social system which find themselves in that historical cul-de-sac.

In other senses White Siberia is distinctly feudal-capitalist. While the quality of the Red forces is pretty uniform (generally mediocre-to-poor), there is a sharp hierarchy of quality between White units. The best are excellent while the worst are of little use, or simply useless, or worse than useless.

The fundamental weakness of the White side is diagnosed:

The filling of the ranks with an unusable mobilization element [ie with conscripts] proved fatal: the heroic remnants of [politically-motivated White Guards] dissolved in the stream of skins.

The phrasing is obscure due to language barrier and the limits of Google Translate, but the meaning is clear: it is impossible for the Whites to build a mass army without fatally diluting their best units. In the Red armies, small numbers of communists proved to be like leavening in the bread, causing the whole mass to rise. But in the White armies, the small politically-motivated element was drowned in a sea of indifference and hostility. This is because the Reds pursued better methods, but more fundamentally because the Reds had a programme that appealed to the masses.

Too clever by half

Another key weakness is explained: that the top brass of the White Army are incompetent whiz-kids, all hype and no substance, who pursue ‘too-clever-by-half’ plans and throw lives and units away. They owe their prominence to the role they played in the semi-guerrilla struggle of summer 1918; they can lead small groups, but have no idea how to assess the fighting strength of this or that unit.

Budberg writes: ‘Siberia fielded not a few thousand young and old knights of duty, pure enthusiasts who raised the sword of the struggle for their homeland.’

But there were no leaders, men of experience and talent, to use these mighty forces; thousands of these fighters are already sleeping in the Siberian land, and all their efforts, their heroic deeds have been brought to naught […]

I envy these fallen ones […]; I ache with my soul for the survivors, for they have had a share of seeing all this and drinking to the bottom of the last bitter cup, not a personal cup, but a Russian cup of grief, shame and death.

The cup of grief overflows

That quote also provides an example of Budberg’s often-excessive prose. Those ellipses in square brackets stand in for text as long again as what is there! He is inclined not only to overwrite, but to repeat the same lamentation again and again at wide intervals, each time with more passion, like a theme in some classical piece. I can see some readers getting annoyed by this. I found it crossed the line into black humour: he keeps lamenting the problems in ever-keener tones of anguish, and things keep finding ways to get worse.

If some publisher decides to put this out in English, they may wish to cut out a few thousand words. Another consideration: I approached this with prior knowledge of the topic, so I was able to follow it easily; to reach a wider audience this source would need to go out armed with a good introduction and copious footnotes.

Go to Revolution Under Siege Archive

[i] I admit, without embarrassment, that I read this text through Google Translate. This programme has come on in leaps and bounds, and I was very impressed with the quality of the translation.

Why Andor is Different

Star Wars: Andor (2022), cr Tony Gilroy. Spoilers Below!

I was not fully sold on the first episode of Andor. It’s basically cyberpunk, I thought: cool and tech-savvy lumpen-proletarians ducking and diving, out for their own profit, defying authority. Nothing wrong with that genre but I’ve seen it before.

Recently I watched some of Rebels and became convinced that the whole Star Wars thing works best as 20-minute cartoons aimed at kids. Adults can watch it, sure, I thought, but our big mistake has been to treat it as anything other than a story and world for children and adolescents. It’s very good as that, but it’s nothing more than that.

Well, Andor has reeled me back in, which is another way of saying I was wrong. Here, in no particular order, are a few of the things that convinced me that Andor is different.

Ferrix

Ferrix is the planet that serves as the primary setting for Andor. It is cold and dusty, with salvage yards and vast cranes and a warren of shops and homes. They have a kind of anvil-angelus, where a guy on top of a tower hammers out ringing peals to the whole town. This feels right for this artisan-industrial place. When the authorities come in uniform, the people bang pots and pans to frustrate any attempt at surprise. There are rats and snitches, but overall it’s a place of plebeian solidarity. But Ferrix really comes into its own in the final episode, when we see how its people do funerals and riots. The funeral tune is haunting. When Bix (Adria Arjona) hears it, she goes to the window of her prison and experiences a moment of spiritual escape. These are her people.

No stormtroopers or TIE fighters

The authorities on Ferrix are not stormtroopers but private corporate security. It’s refreshing that for the first few episodes we don’t see a single stormtrooper or TIE fighter. There are no lightsabers or Boba Fett masks, Star Destroyers or X-wings, few cameos from familiar characters. The creators of Andor trust that we don’t need to have nostalgic artefacts pushed into our faces every few scenes.

Revolution

In Andor, for the first time in a Star Wars story, revolution is not about a band of wisecracking misfits doing heists. It’s about the masses – 5,000 slaves breaking out of a high-tech factory-prison, or a working-class community turning a funeral into a mass act of political resistance. Brasso (Joplin Sibtain) embodies this. It’s about manifestos – such as that of Nemik (Alex Lawther) which combines with Cassian’s own experiences to politicise him.

Morals

We see secret underground work, clandestine agents one step ahead of the Empire’s political police. The revolutionaries are not magically exempt from having to do bad things. In fact, their precarious position means that few methods are open to them aside from those methods which eat away at their souls and compromise their principles.

At the same time, there’s no shabby ‘both sides’-ism or ‘grimdark’ tropes. The means pursued by the Empire and the rebels are suited to their ends and circumstances. Pluck and compassion on one side, cackling villainy and martinets on the other – that’s fine for cartoons, but it’s not what we see here.

Evil Empire

There’s plenty of other things I could talk about – the compassion and hint of humour with which the script deals with the unsympathetic Syril (Kyle Soller), a corporate security officer on Andor’s trail; the intriguing side-story on Coruscant starring Mon Mothma (Genevieve O’Reilly); the rise to power of Dedra Meero (Denise Gough), the Empire’s answer to J Edgar Hoover.

A cynical part of me didn’t want to write this. What am I doing, providing free publicity for Disney, who certainly don’t need any help from me?! Looked at coldly, what have we got here? The corporate entertainment machine has gotten tired of stimulating the nostalgia centres of our brain and is trying to expand its cultural reach by stimulating the political and intellectual zones for a while instead. And while Andor may contain traces of political sophistication, it’s not exactly a Ken Loach film.

Anyway, if you enjoy it you enjoy it, no need for hand-wringing. But it’s a show that provokes interesting thoughts about the nature of pop culture today.

This is the nature of pop culture under the vast monopolies of late capitalism: the big budgets go to pre-existing worlds and stories.

(A side-note: It’s frankly weird and pathological that so many people refer to stories and imaginary worlds as ‘franchises’ and ‘properties.’ Can we all stop doing that, please?)

Where was I? Yes, pop culture today. For example, the Taxi Driver of the 2010s had to be filtered through comic-book superhero stories in order to get made: that was the Joker movie (I know that’s DC and not Marvel/ Disney but the same point applies).

If popular culture is a galaxy then Disney is the evil empire that is trying to dominate it. Sure. But don’t forget what Nemik said in his manifesto in the final episode. This homogenisation of culture goes against the grain of the natural creativity of humanity. So insurrection is inherent even in the fabric of the empire itself. Hence Andor.

18: The Chelyabinsk Trap

On the Eastern Front in July 1919, the White regime of Admiral Kolchak was reeling after its armies were driven out of the Ural Mountains. But the Siberian Whites made an audacious throw of the dice, triggering one of the largest battles of the Civil War.

To set the scene for us, here is the diary of General Alexei Pavlovich Budberg, a minister in Kolchak’s government. He recorded his horror and frustration as things fell apart:

July 19th 1919:

Head is spinning from work […] To our disadvantage, the Red Army soldiers at the front were given the strictest order not to touch the population and to pay for everything taken […] The admiral gave the same orders […] but with us all this remains a written paper, and with the Reds it is reinforced by the immediate execution of the guilty.

July 20th 1919:

[…] self-seekers and speculators are white with fear and flee to the east; tickets for express trains are sold with a premium of 15-18 thousand rubles per ticket.

July 22nd 1919:

The Ministry of Railways receives from the front very sad information about the outrages and arbitrariness committed during the evacuation by various commanding atamans and privileged rear units and organizations; all this greatly complicates the hard work of evacuation […]

Hints of a planned White counter-attack do not give Budberg any relief. On the contrary, he was filled with foreboding:

July 23rd 1919:

Something mysterious is happening at headquarters: operational reports have been temporarily suspended…

In the rear, uprisings are growing; since their areas are marked on a 40-verst map with red dots, their gradual spread begins to look like a rapidly progressing rash.

July 24th 1919:

The mystery […] has been aggravated: to all my questions I receive a mysterious answer that soon everything will be resolved and that very big events will take place that will drastically change the whole situation.

July 25th 1919:

Only today did I learn at headquarters that [General] Lebedev, with the cooperation of [General] Sakharov, wrested from the admiral consent to some complex offensive operation in the Chelyabinsk region, promising to completely eliminate the Reds […]

Undoubtedly, this is Lebedev’s crazy bet to save his faltering career and to prove his military genius; it is obvious that everything is thought out and arranged together with another strategic baby Sakharov, who also yearns for the glory of the great commander.

Both ambitious people obviously do not understand what they are doing; after all, the whole fate of the Siberian white movement is put on their crazy card, because if we fail, there is no longer salvation for us and we will hardly be able to restore our military strength…

Chelyabinsk

The city of Chelyabinsk lies amid a cluster of lakes, a few hours by rail east of where the Ural Mountains fall away to the plains. It can be regarded as ground zero of the Russian Civil War: it was there that a brawl between Czechs and Hungarians led to the revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion.

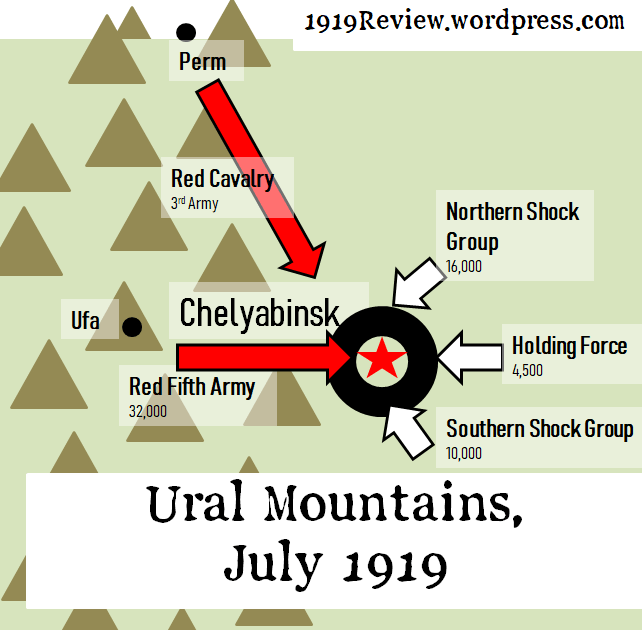

At the end of July the Red Fifth Army came down from the Mountains into the lake country. This was the same Fifth Army that had held the line at Sviyazhsk and then crossed the Volga to seize Kazan. Trotsky and Vacietis counselled caution and rest for Eastern Army Group after it drove back the White Spring Offensive. But the new commander-in-chief, the military specialist Kamenev, argued for a hot pursuit of the Whites right into the heart of Siberia. So far Kamenev had been vindicated. The same Chinese Reds, led by Fu I-Cheng, who had lost Perm the year before had recaptured it. The Red commander Frunze had taken Ufa after a terrible and bloody fight with Kappel.[i]

Now the Fifth Army was advancing on Chelyabinsk. But Kolchak, on the advice of his young generals Lebedev and Sakharov, had decided to turn the city into an elaborate trap. The Reds would be allowed to seize the city – then encircled in it, and destroyed.

On July 24th a workers’ uprising began in the city. It was led by an underground Bolshevik organisation that had suffered under the counterintelligence operations of the ‘very cruel’ Colonel Sorochinsky. The Red Fifth Army hurried to the aid of the rebels, and linked up with them. Railway employees sabotaged the White defence: they derailed one armoured train and diverted another into a dead end. The city fell, and the Reds captured many rifles and machine-guns. Morale was good, energy high: Red detachments at once began scouting and advancing out from the city through the suburbs and villages.

But to the north, south and east, White shock groups and formations were closing in on the city to encircle and destroy the Fifth Army.

Let’s pause and get a proper sense of scale. The last time this series zoomed in on a particular battle, that of Kazan, it was easy enough to visualise. In an arena measuring forty kilometres by twenty, there were between ten and twenty thousand soldiers per side.

The Battle of Chelyabinsk compels us to think bigger, on a scale of at least 80 square kilometres.

There were 32,000 rifles and swords in the Red Fifth Army. On the side of the Whites, there were around 30,000 as well: the Northern shock group numbered 16,000, the southern shock group 10,000, and there were 4,500 to the east holding the line between the two.

The Trap

Let’s zoom in on one of those fighters, a White cavalry officer named Egorov.

At four in the morning of June 25th Egorov was waiting with his regiment at a crossroads near one of the several lakes north of Chelyabinsk. Egorov’s Mikhailovsky Regiment consisted of 150 mounted soldiers – ‘rather motley,’ by his own admission, old and young, mostly infantrymen mounted rather than ‘real’ cavalry – along with soldiers on foot.

They were ordered to gather here before seizing the village of Dolgoderevenskaya, north of Chelyabinsk.

Egorov and his men were still stinging from the postscript added to their orders: ‘I advise the regiment commander, Colonel Egorov, to abandon this time the usual delay…’

Adding insult to injury, the Mikhailov Regiment was on time. They were waiting in the early hours of the morning for the Kama Division to show up.

‘To the right and left I hear voices: “Why wait for the Kamtsy?.. Move!.. Enough of the Reds!”’

Egorov decided it was time. The regiment sneaked up close to the village. A local Cossack boy told them there were many Reds in the village, but a lot of them were asleep.

The attack began. White cavalry broke through the outskirts of the village without a shot being fired, and before most of the Reds were awake the White cavalry had dispersed all over the streets while infantry attacked from the west.

‘And only after that,’ writes Egorov, ‘the first rifle shots were heard.’

He was watching from a nearby hillside. The rifle fire intensified, and the sound of the Russian war-cry, ‘Urrah!’ came to him. After an hour of fighting, the Reds fled to the next village.

As Egorov entered the village he heard someone shout: ‘Mister Colonel! Trophies!’

His men were looting what the enemy had left behind: gramophones and field-kitchens. Egorov reckoned the Reds had, in their turn, taken the gramophones from the houses of priests and merchants.

But the Whites got carried away in the celebrations. The Reds counter-attacked and caught them unawares. Fortunately for Egorov, the Kamtsy arrived – the stragglers Egorov had not bothered to wait for – and they had artillery. By three in the afternoon the Reds had been driven back again. Egorov and his cavalry mounted up, and this time pursued them, and drove them out of the next village as well. The Reds began to retreat all along the front.

Egorov’s assistant, a Tatar, had taken a bullet in the arm during the day’s fighting. He was unperturbed. That night at dinner he drank heartily. Then he excused himself, went out into the hall, and removed the bullet with a penknife.

These battles were part of the advance of the northern shock group. It was very successful; it reached the Yekaterinburg-Chelyabinsk railway line, cutting off the Fifth Army and threatening it from the rear.

On 27 July the southern shock group advanced. Its purpose was to link up with the northern group, completing the encirclement. The southern group was commanded by Colonel Kappel, who had led the Whites at Kazan. Kappel was a relic of the late Komuch government and its ‘People’s Army,’ now serving Kolchak and the Whites. There were others present at Chelyabinsk for whom Komuch had served as a Red-to-White pipeline or gateway drug. The workers’ militia of Izhevsk were there, going into battle to the sound of accordions.

Meanwhile the 4,500 White Guards in the middle advanced west into the outskirts of Chelyabinsk.

Another White veteran recalled: ‘On one of the days, apparently on the 27th or 28th […] we found ourselves 3-4 versts from Chelyabinsk and were about to have dinner there.’

He and Egorov and Kappel had good reasons to feel confident. Many would have believed that just as Denikin was advancing in South Russia, they were about to turn the tide in the east.

Resistance

According to the plan, the Reds should have been panicking and falling to pieces by now. Generals Sakharov and Lebedev were young officers who had learned most of what they knew during the period of the Czechoslovak Revolt of 1918. They had led irregular detachments against untrained Red Guards.

But these Reds in Chelyabinsk were made of something else. They held firm. Kappel engaged in heavy battles to the south of the city, but his forces could not break through.

The Chelyabinsk revolutionary committee put out a call, and 8,000 miners and other workers joined the defence, arms in hand. 4,500 others joined work detachments, building defences and supporting the troops. The centre group of Whites could not advance further, and got bogged down in the outskirts.

Why couldn’t the Whites make any headway? We noted in a previous episode that they had raised two divisions of young conscripts. These forces had not even been trained when they were flung into the battle at Chelyabinsk. To encircle an enemy army would have been a challenge at the best of times. The White officers were ordered to spring the trap with personnel who did not know what they were doing.

In Russia, soldiers with rifles are called streltsi, literally ‘shooters.’ One veteran wrote to the Chelyabinsk local newspaper in the 1970s, recalling his days as an officer leading White streltsi:

I was a participant in the battles near Chelyabinsk on July 25-31, 1919, not in the Red Army, but in the White Army, in […] the 22nd Zlatoust regiment of Ural mountain shooters, which they practically were not [sic], since […] they were not even trained at all how to shoot.

During the battle, up to 80% of the 13th Siberian rifle division went over to the Reds. They surrendered in their thousands, bearing US Remington rifles and wearing British uniforms.

It wasn’t just the new conscripts. In the headlong retreat since May, divisions had winnowed to regiments, regiments to, in one case, a ragged group numbering only seventy. Typhus had raged through the White units. Many of the replacements were young Tatars, like Egorov’s friend. Many of these couldn’t speak Russian.

Kappel’s Volga Corps had taken a battering in recent months. Instead of getting time to recover, they, like the new recruits, were thrown into battle.

On the other side, the Red Fifth Army was experienced and energetic. And they had a political backbone: in the 27th Division alone there were 600 Communist Party members.

But the fighting was fierce. According to one source there were 15,000 Red and 5,000 White casualties.[iii] According to other sources, the Whites lost 4,500 killed and wounded, while 8,000 or even 15,000 were captured, and the Red casualties numbered 2,900.

The Reds held on in the centre and south, then reinforced the vulnerable north. They built up a shock group of their own and between July 29th and August 1st defeated five enemy regiments north of the city. I assume this involved sweeping through the villages Egorov and co had taken nearly a week earlier. Perhaps the gramophones changed hands again.

Cavalry units from the Third Red Army at Perm were hurrying to the aid of Chelyabinsk and threatened the Whites’ northern shock group. The Izhevsk militia was sent to meet them, but the Izhevtsi suffered heavy losses at the village of Muslyumovo. The northern shock group had itself suffered a series of shocks. Its position was untenable.

Back in Omsk, General Budberg was asked by Kolchak what he thought of the Chelyabinsk Operation.

July 31st

I reported to him that I think that now it is necessary to immediately stop it and order to do everything possible to withdraw the troops involved in it with the least damage to them.

The admiral was silent, but asked to speed up the dinner, then went into the office to Zhanen, where he signed a telegram to Lebedev about the retreat; he is very gloomy and anxious.

August 1st

Everything connected with the Chelyabinsk adventure, and most importantly, my powerlessness to stop it and prevent all its consequences, led me to the decision to ask the admiral to dismiss me from my post, and if it is impossible to give [me] a place to the front, then to [accept my resignation].

Budberg’s request was refused, and so he was forced to around Omsk as an agonised and impotent witness to further disaster.

Red advance

From August 1st the Reds were on the offensive. The White retreat eastward grew more chaotic.

Many in the White camp had warned against the Chelyabinsk operation. They favoured instead a defensive strategy: digging in behind the Ishim and Tobol rivers and buying time to train up the new units. After ‘the trap failed to close’[iv] at Chelyabinsk, the White armies were demoralised and sorely depleted. Digging in was less feasible than before, but even more urgent.

The Siberian Whites were not finished all at once. In late July the Siberian Cossack host joined Kolchak’s cause – too late to help at Chelyabinsk, but just in time to give Kolchak and others a false hope in a renewed offensive strategy. Nonetheless the Red advance across Siberia was indeed delayed by serious battles with the Cossacks and on the defence lines of the rivers.

Crisis in White Siberia

But the Battle of Chelyabinsk is not so much a story of Red victory as one of White defeat. That defeat is interesting because in every way it was symptomatic of the crisis that was developing in Kolchak’s Siberia.

Behind White lines there reigned a regime of corruption and terror that exceeds the most lurid caricatures of the Red side. Untrained and demoralised men sent to fight the partisans would torment the farmers, burn villages, loot, torture and kill. Bodies hung from the telegraph-poles along the Trans-Siberian railway.[v] Further east under Semyonov and Ungern, as we have seen, things were even worse.